Curator’s Favorite: Cyclorama in Philadelphia

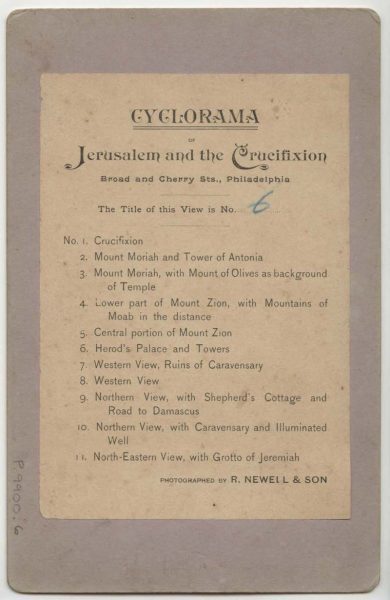

Recently cataloged as part of a project generously supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities to process, catalog, and digitize many of our ephemera collections, this series of eleven stereographs created by the Philadelphia photographic firm R. Newell & Son documents the Jerusalem on the Day of the Crucifixion cyclorama. The cyclorama was displayed in Philadelphia at the northeast corner of Broad and Cherry Streets from 1888 until 1890 in a circular brick building constructed specifically for this visual form of entertainment.

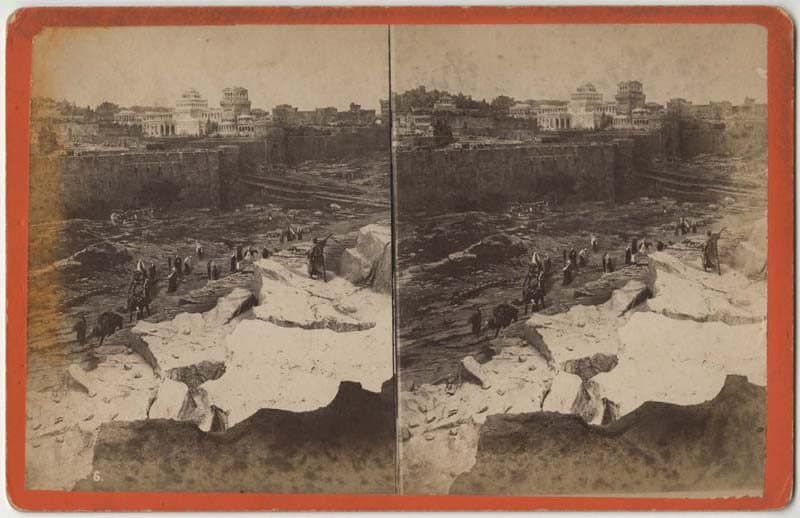

R. Newell & Son, “Herod’s Palace and Towers,” No. 6 in Cyclorama of Jerusalem and the Crucifixion. Broad and Cherry Sts., Philadelphia. Albumen print on stereograph mount. Recto.

R. Newell & Son, “Herod’s Palace and Towers,” No. 6 in Cyclorama of Jerusalem and the Crucifixion. Broad and Cherry Sts., Philadelphia. Albumen print on stereograph mount. Verso.

Part theater, part fine art, cycloramas were an accessible, popular urban spectacle in America and Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century. These panoramic, cylindrical paintings provided spectators with 360-degree views of life-like dramatic historical scenes. Hundreds of cycloramas commemorating battle scenes were created after the Civil War, including Paul Philippoteaux’s “Battle of Gettysburg,” installed in 1885 in the same circular brick building as the Jerusalem panorama on North Broad Street. (That cyclorama is known to have been destroyed, but another of Philippoteaux’s four versions has been restored and is now on view at Gettysburg National Park Museum and Visitor Center.)

Spectators without the time or financial means to travel could obtain a view of popular tourist destinations by visiting the cyclorama: “The stay-at-homes need not despair. The outlay of 50 cents, car fare, and 2 or 3 hours of time will enable every one to take a trip to the Orient. Jerusalem is still open at the Cyclorama, BROAD and CHERRY Streets, all day and evening until 10 o’clock.”

Inspired by a Jerusalem cyclorama created by German artist Karl Frosch in Munich, Germany, the canvas in Philadelphia covered approximately 20,000 square feet and included the painting talents of John O. Anderson, A. G. Reinhart, Thaddeus Welch, Edward J. Austin, and E. Gros. By July 1889, a lecture playing on the phonograph or “Edison’s talking machine” accompanied the panorama. Tens of thousands of visitors viewed the cyclorama before it traveled to Boston.

The titles of the stereographs representing different sections of the panorama in the series include “Crucifixion,” “Mount Moriah and Tower of Antonia,” “Mount Moriah, with Mount Olives as background of Temple,” “Lower Part of Mount Zion, with Mountains of Moab in the distance,” “Central portion of Mount Zion,” “Herod’s Palace and Towers,” “Western View, Ruins of Caravensary,” “Western View,” “Northern View, with Shepherd’s Cottage and Road to Damascus,” “Northern View, with Caravensary and Illuminated Well,” and “North-eastern view, with Grotto of Jeremiah”.

Linda Wisniewski

Visual Materials Cataloger

Sources:

“Cyclorama” in Heidler & Heidler’s Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2000), 541-543.

“Amusements.” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 3, 1890.

“Cycloramas.” Jackson, Encyclopedia of Philadelphia, vol. II, 535-536.