Treasures from the Library Company of Philadelphia

During the years of the Civil War–with money scarce, prices high, and many of the Library Company’s members in the army–it took all of Librarian Lloyd Pearsall Smith’s ingenuity to maintain the currency of book purchases. Dictated by the reading habits of members, these were increasingly dominated by novels from such once-popular, but now almost forgotten, authors as Ellen Price Wood, Lady Blessington, and Mayne Reid, as well as French texts from the prolific Alexandre Dumas and George Sand.

During the years of the Civil War–with money scarce, prices high, and many of the Library Company’s members in the army–it took all of Librarian Lloyd Pearsall Smith’s ingenuity to maintain the currency of book purchases. Dictated by the reading habits of members, these were increasingly dominated by novels from such once-popular, but now almost forgotten, authors as Ellen Price Wood, Lady Blessington, and Mayne Reid, as well as French texts from the prolific Alexandre Dumas and George Sand.

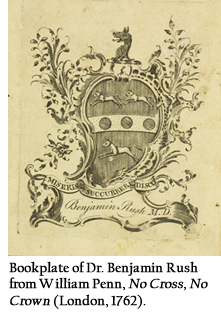

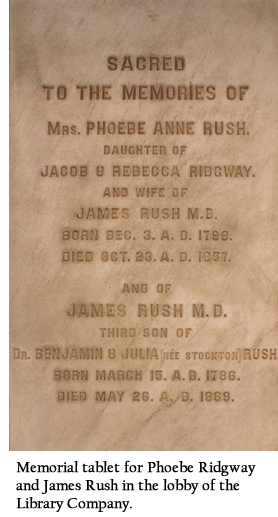

In 1869, Shareholder Dr. James Rush died and left the Library Company his estate, amounting to almost one million dollars. Rush was the son of physician-patriot Benjamin Rush and husband and heir of Phoebe Ann Ridgway Rush, who had inherited a portion of her father Jacob Ridgway’s immense fortune and had predeceased her husband. The couple had been childless. The will, as presented to the Directors of the Library Company by Henry J. Williams, Rush’s brother-in-law, sole executor, and himself a long-time Library Company Director, stipulated that the institution would receive the large  bequest only if it met certain conditions.

bequest only if it met certain conditions.

With the bequest the Library Company was to purchase a plot of adequate size and there build a “fire-proof building sufficiently large to accommodate and contain all the books of the Library Company of Philadelphia . . . and to providefor its future extension.” But in addition to that very prudent and unexceptionableprovision Rush insisted on other, much more eccentric conditions.

Let [the library] rest in a modest contentment in the useful quality of its volumes for the benefit, not the amusement alone of the public, nor let it over an ambitious store of inferior printed paper, flap its flimsy leaves, and crow out the highest number of worthless books. Let it be a favor for the eminent works of fiction to be found upon the shelves; but let it not keep cushioned seats for time-wasting and lounging readers, nor place for every-day novels, mind-tainting reviews, controversial politics, scribblings of poetry and prose, biographies of unknown names, nor for those teachers of disjointed thinking, the daily newspapers. …In short, let the managers think only of the intrinsic value of additions to their shelves.

Let [the library] rest in a modest contentment in the useful quality of its volumes for the benefit, not the amusement alone of the public, nor let it over an ambitious store of inferior printed paper, flap its flimsy leaves, and crow out the highest number of worthless books. Let it be a favor for the eminent works of fiction to be found upon the shelves; but let it not keep cushioned seats for time-wasting and lounging readers, nor place for every-day novels, mind-tainting reviews, controversial politics, scribblings of poetry and prose, biographies of unknown names, nor for those teachers of disjointed thinking, the daily newspapers. …In short, let the managers think only of the intrinsic value of additions to their shelves.

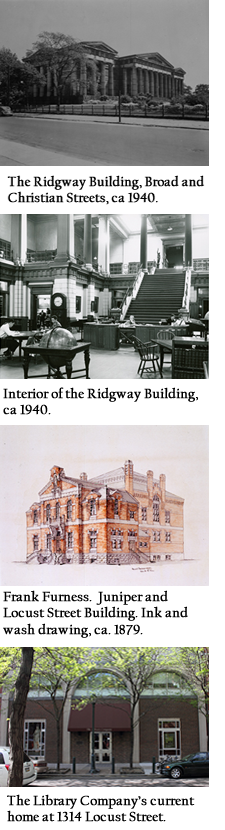

A divided Library Company membership was torn between the need for the million-dollar bequest and disapproval of Williams’s specific plans for a massive Greek Revival structure designed by Addison Hutton at Broad and Christian Streets, far from the center of town, and the shareholders only narrowly approved acceptance of the bequest with its restrictive covenants. In 1878 the Library Company rather reluctantly took possession of the impressive edifice, named the Ridgway Library in honor of the original source of the funds which made it possible. To satisfy members and readers who had no intention of going down to South Philadelphia to browse or pick up the latest novels and biographies, however, a second structure was commissioned from Frank Furness and built at Juniper and Locust Streets in 1880 to house contemporary books and periodicals.

Also part of the Rush bequest where his library and papers, which included almost all the books of his celebrated father Benjamin Rush (who had probably the largest and best medical collection in the United States at the time of his death in 1813) and the manuscripts of many of James’s writings and lectures, notebooks, ledgers, medical records, and letters. His collection ranged from the valuable reference material that he had accumulated for studies he wrote on the human voice and the intellect to expensive, illustrated books on art, architecture, and antiquities.

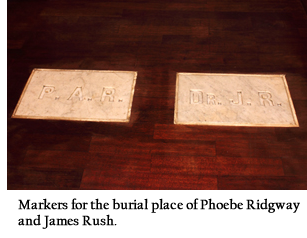

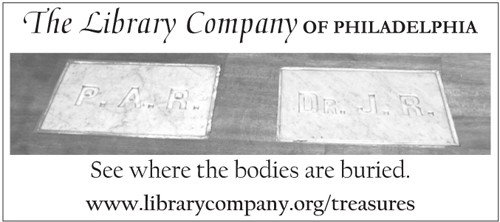

Rush, who had been a studious, somewhat misanthropic, and definitely eccentric gentleman, set forth a number of curious additional stipulations in his will, including setting a limit of 969 on the total number of Library Company shareholders at any one time, requiring that his own publications be kept in print in perpetuity…and requiring that he and his wife Phoebe Ann be interred under the new Ridgway Library building. The decree of Philadelphia’s Orphan’s Court in the 1960s that permitted the Library Company to sell the Ridgway Library building and move to our current location included a provision requiring us to bring James and Phoebe Ann with us to 1314 Locust Street, where their grave markers grace our lobby today. Subsequently, the Library Company also became the final resting place for long-time Librarian Edwin Wolf 2nd, whose ashes are sealed in a lobby wall.

Rush, who had been a studious, somewhat misanthropic, and definitely eccentric gentleman, set forth a number of curious additional stipulations in his will, including setting a limit of 969 on the total number of Library Company shareholders at any one time, requiring that his own publications be kept in print in perpetuity…and requiring that he and his wife Phoebe Ann be interred under the new Ridgway Library building. The decree of Philadelphia’s Orphan’s Court in the 1960s that permitted the Library Company to sell the Ridgway Library building and move to our current location included a provision requiring us to bring James and Phoebe Ann with us to 1314 Locust Street, where their grave markers grace our lobby today. Subsequently, the Library Company also became the final resting place for long-time Librarian Edwin Wolf 2nd, whose ashes are sealed in a lobby wall.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!