Shall We Play A Game?

For many “Shall We Play a Game?” evokes the ominous query that nearly set off nuclear war when asked by the hacked, government supercomputer in the 1980s movie War Games. The game chosen by the computer hacker was one with real world implications of global annihilation.

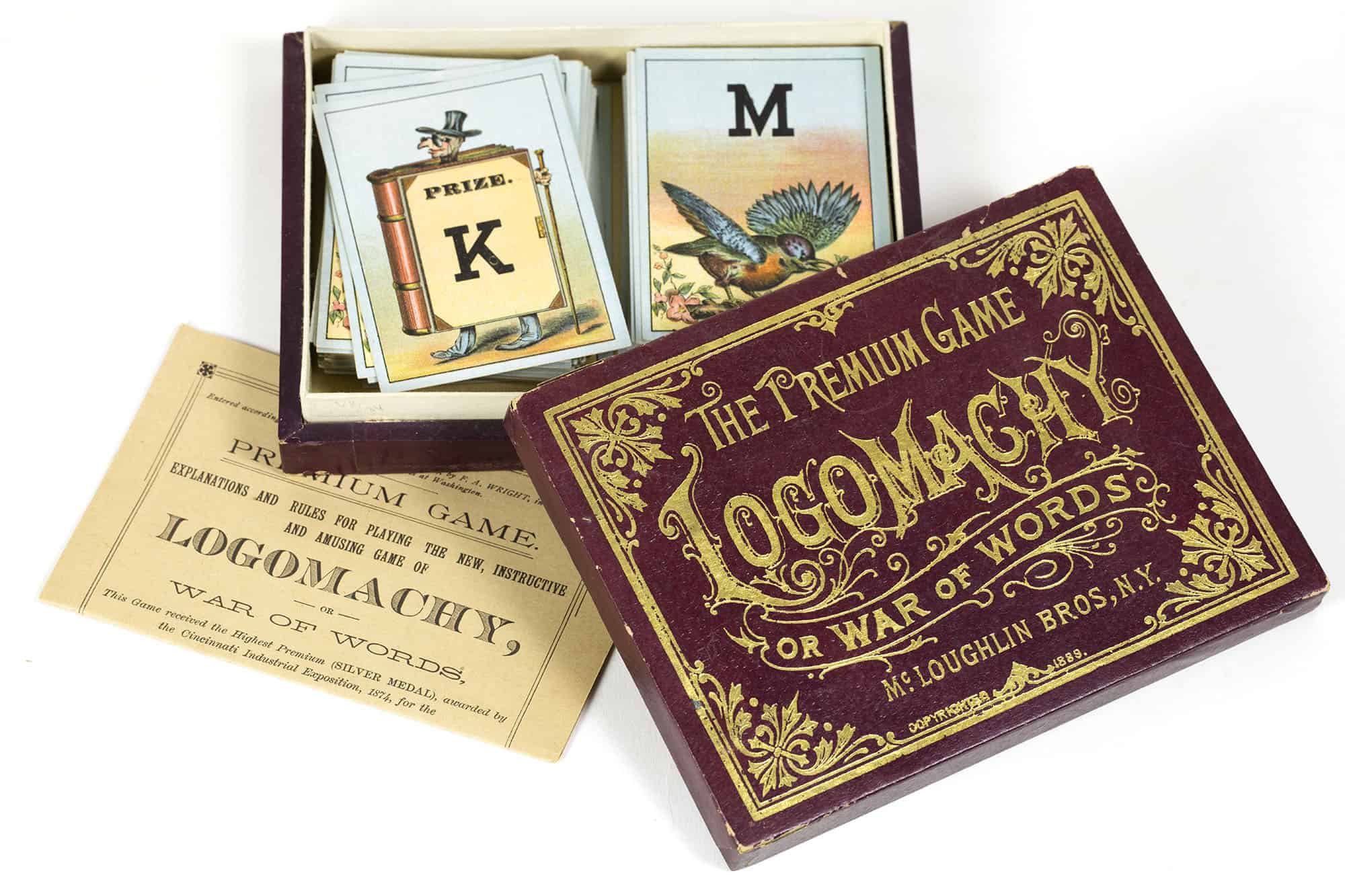

Asking someone to play a parlor game does not typically bring such consequential implications to mind. However, indoor games have generally been devised to be more than a means of entertainment. Recently, long-term donor and Trustee Emeritus Michael Zinman gave the Library Company a number of Victorian games that augment our growing collection of these artifacts. Ones comprised of paper boxes, cards, wooden pieces, balls, and/or ceramics. Primary sources embodying the popular culture of their era, the games also represent the visual culture of their period of production. Eye-catching, illustrated chromolithographed box covers; cases designed as novelties; and pictorial symbols on games pieces epitomized the visual world that inspired them.

While some like the marble-wrangling puzzle Pigs in Clover challenged hand-eye coordination, others like Logomachy or War of Words served as pedagogical exercises in which players “fought” to craft words from cards containing letters of the alphabet. Both were popular in the 1880s and 1890s. Logomachy manufactured by McLoughlin Bros., the New York company that specialized in works published for children, also became a mainstay amusement among adults. Society notices in newspapers noted the game at wedding anniversary celebrations like that of an Arizona couple married twenty-five years in 1898. The couple even created custom bell-shaped souvenir score cards for their game-playing guests.

In the case of Pigs, an even bigger fad than Logomachy, games of a legal nature ensued. Designed and patented in 1889 by innovative toy maker and manager of Waverly Toy Works C.M. Crandall (1833-1905), Pigs sold a purported million copies in its first year of production. The popularity evoked imitators, as well as legal action. The toy manufactory’s financier Moses Lyman visited multiple cities as reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer in April 1889 to “put an end to the illegal manufacture of Pigs in Clover upon which he has a copyright.” The article further noted that Lyman had caused a New York manufacturer to be “under bail for the violation of the US trademark law.” By the time the patent was awarded to Crandall in September 1889, various stories about the true creator of the game had circulated in the press. A German student of physiological psychology was noted, as well as a pig farmer named “Moses Lyman.”

Artifacts of 19th-century visual and popular culture, Victorian games ask more than just to be played. They also ask to be seen and understood as a capsule of the lives of the people who imagined them, designed their packaging, and engaged with them as a means of recreation and education.

Erika Piola

Associate Curator, Prints and Photographs and Director, Visual Culture Program

Sources:

Philadelphia Inquirer, April 9, 1889

Weekly Journal Miner, October 12, 1898

Worcester Daily Spy, April 22 1889

![zinman-games-p-2017-69 Charles Martin Crandall, Pigs in Clover ([Waverly, N.Y.]: [Waverly Toy Works], [ca. 1889]).](https://librarycompany.org/wp-content/uploads/zinman-games-p-2017-69.jpg)