Every Man’s House a Daguerrean Gallery

Daguerreotypes reigned supreme for only a little over a decade, but during that period they became an integral part of American life. It has been estimated that in 1853, over three million daguerreotypes were taken. Daguerreotypes could celebrate happy milestones, serve as mementos of far away family and friends, or serve as a treasured reminder of a deceased loved one. Daguerreotypes entered the American psyche so deeply that the word came to describe not only the physical object, but the supposed truth revealed by the image.

Click images below for larger view in a new window.

Daguerreotypists in Philadelphia: Growth from 1846 to 1856.These two maps indicate how pervasive daguerreotype studios had become in the city’s landscape in just a single decade. Fewer than twenty daguerreotypists operated in Philadelphia in 1846, but that number had grown to more than one hundred by 1856 (although in 1856 some of these studios may have offered other photographic processes as well). Studios clustered east of Broad Street along Chestnut and Market Streets and along 2nd Street north of Arch Street. |

|

The Daguerreotype: A Magazine. Boston: J. M. Whittemore, 1847. Gift of Miss Smith.According to the introduction, “The Daguerreotype is, as the name imports, designed to reflect a faithful image of what is going on abroad in the great Republic of Letters.” Charting the progress of the photographic process was not part of its mission. Although the publishers intended to issue the periodical weekly, it actually came out every other week and only survived until 1849. |

|

Frances S. Osgood. “Daguerreotype Pictures Taken on New Year’s Day,” in Graham’s Magazine of Literature and Art, November, 1843. Gift of E. K. Martin.By the end of 1842, Graham’s Magazine claimed a circulation of 50,000 subscribers, who enjoyed monthly issues filled with engravings, short stories, and poems. Frances Osgood was a popular author and a frequent contributor to Graham’s, but her fame has been less long-lasting than other contributors such as Edgar Allan Poe, to whom she was romantically linked by gossips of the day. Despite its title, Osgood’s story had nothing to do with sitting for a daguerreotype. “Daguerreotype Pictures” referred to vignettes or character studies revealed in the story. |

|

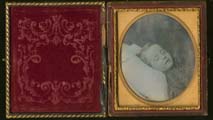

McClees & Germon. Post-mortem of an Unidentified Boy. Sixth-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, 1854. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.The pain of losing a child could perhaps be slightly diminished if a family member had a daguerreotype of their loved one’s face to treasure. Post-mortem daguerreotypes were taken in the home of the deceased with the subject usually lying in bed or on a sofa, thus embodying the Victorian idea of death as a “last sleep.” |

|

Anna S. Roberts. “The Little Shadow,” in Forest Flowers of the West. Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1858. Gift of Solomon W. Roberts.Poetess Anna Roberts supposedly addressed this poem in 1855 to the daguerreotype of her recently deceased daughter, Elizabeth. The poem was discovered among her papers upon her death three years later. The black- edged page on which the poem appears was added to the 1858 edition of Roberts’s poetry book, which was donated to the Library Company in 1859 by her husband. |

|

“The Husbands’ Daguerreotype,” in The Photographic Art-Journal. February 1852.The need to have a tangible reminder of a departed loved one is the theme of this poem written by a female daguerreotypist from New York State. For $5.00 a year subscribers from around the country including Marcus Root and McClees & Germon of Philadelphia received monthly issues of The Photographic Art-Journal, which included technical articles, reports on exhibitions, and articles urging the formation of a national daguerreian association and the need to keep prices at certain levels to avoid debasement of the profession by the “25 cent fraternity.” |

|

Martha Cameron. “To The Daguerreotype of an Estranged Friend,” in Peterson’s Magazine, January 1854. Gift of Randall Miller.In Cameron’s poem a daguerreotype of a former friend remains the tangible and treasured legacy of a soured relationship. |

|

Julianna Randolph Wood Holding Daguerreotype of Richard Davis Wood. Quarter-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1845. Gift of Wawa, Inc.Richard D. Wood, a wealthy Philadelphia Quaker with interests in banking, iron, and coal, frequently traveled for his business. On May 15, 1845, a week before leaving on a three-month trip out West, he wrote in his journal, “Went with wife to be daguerreotyped, and succeeded in getting a good likeness of her.” Knowing how long her husband was to be away, perhaps Julianna requested that this daguerreotype show her holding her soon-to-be-absent husband’s image. |

|

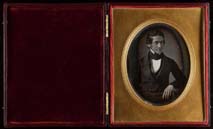

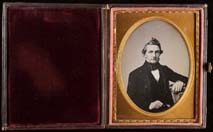

Richard Davis Wood. Quarter-plate daguerreotype. Probably Philadelphia, ca. 1844-1845. Gift of Wawa, Inc.This daguerreotype bears a striking resemblance in pose and appearance to the daguerreotype of Richard Wood held by his wife (displayed in this case), although it is housed behind a different mat. Richard Wood had a long standing interest in daguerreotyping, having visited Robert Cornelius’s studio in its first week of operation and declaring that day “one of the most pleasantest days ever known.” |

|

Montgomery P. Simons, attr. Algernon Sydney Roberts. Quarter-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, 1848.According to his diary, Philadelphia hardware store clerk Algernon Roberts visited Simons’s studio two times in the fall of 1848. Algernon’s Uncle George Roberts had sent him $5.00 to cover the cost of a book and a daguerreotype portrait which he wished to have Algernon send to him in New Orleans. George Roberts’s daguerreotype portrait is also on display in this case. |

|

George Washington Roberts. Quarter-plate daguerreotype, ca. 1848.George Roberts left Philadelphia and moved to New Orleans in 1843 to work for a druggist. His request for daguerreotypes of his nephews Algernon and Sidney Roberts recorded in Algernon’s diary may have been a way to dispel homesickness and follow the progress of his nephews into adulthood. He, in turn, may have sent this daguerreotype of himself to Algernon, whose daguerreotype portrait can also be seen in this case. |

|

Samuel Broadbent. Double Portrait of George E. Carter. Sixth-plate daguerreotypes. Philadelphia, 1855. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.Sometime around the age of five, boys made the transition from wearing dresses to trousers, and this momentous occasion in George Carter’s life was captured in these two daguerreotypes. Perhaps burdened with new masculine responsibilities, George looks slightly worried in his long pants. A head rest, whose base is visible near George’s feet, helped to keep him still, as did the instruction to place one hand on the chair. |

|

Daguerreotype Pin, 1848. Gift of Radclyffe F. Thompson.This two-sided brooch contains an image of Julianna R. Wood on one side and her daughter Caroline on the reverse. The pin with its engraved date probably commemorated Caroline’s tenth birthday. Daguerreotypists including the Langenheims, James McClees, and Marcus Root all advertised their ability to set daguerreotypes into jewelry. Bracelets, earrings, pendants, and watch fobs were all items into which daguerreotypes were placed. |

|

Advertisement in the December 25, 1844, issue of the Public Ledger. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.This advertisement for William and Frederick Langenheim’s studio promoted the idea of exchanging daguerreotype portraits as gifts during the holiday season. From a small size suitable for placing in a jewelry setting to a much larger size, a daguerreotype would make “a splendid keepsake for the ensuing holidays.” |

|

“If our children and children’s children to the third and fourth generations are not in possession of portraits of their ancestors, it will be no fault of the Daguerreotypists of the present day; for verily, they are limning faces at a rate that promises soon to make every man’s house a Daguerrean Gallery.”

T. S. Arthur. “The Daguerreotypist,” in Sketches of Life and Character. Philadelphia: J. W. Bradley, 1850.