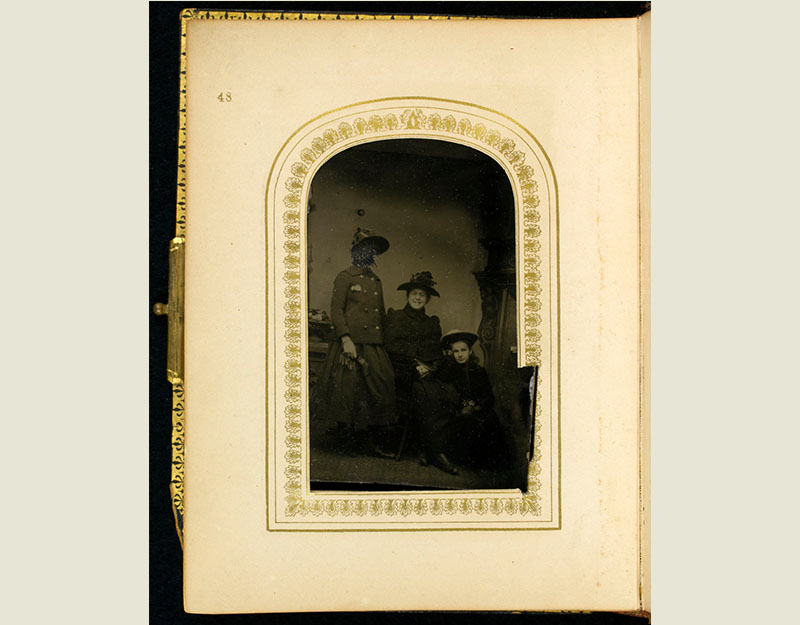

Photographs depicting students of the Ogontz School for Girls, taken by H. Parker Rolfe in 1892-1893.

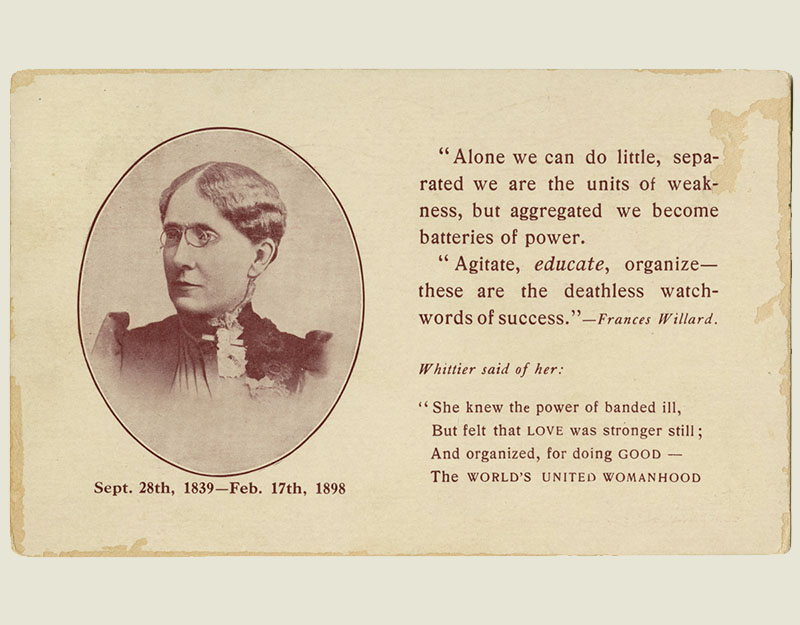

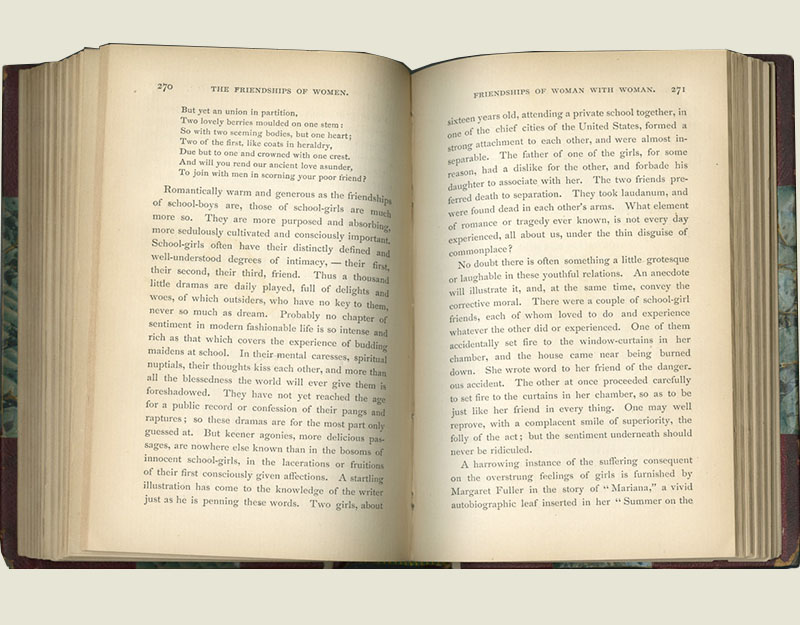

Typically, women's lives were closely circumscribed by family obligations. Yet many girls formed lasting bonds in school and sometimes maintained these relationships into adulthood. This was especially likely when the women strove to be economically independent through their work.

The Ogontz School for Girls, founded as the Chestnut Street Seminary in 1850, moved to financier Jay Cooke's estate Ogontz in 1883. Its students came from elite families from the Philadelphia region and elsewhere. Many of the more than 200 photographs in an album owned by Ida F. Drew, a student from Chicago, were taken in the 1892-1893 academic year by professional photographer H. Parker Rolfe (1856-1939).

Note the girl in the front row of the astronomy class wearing a necktie. In the 1890s, wearing a tailored shirt paired with a necktie was a fashionable look for women, so it's hard to know whether this young woman was challenging gender norms of the day.