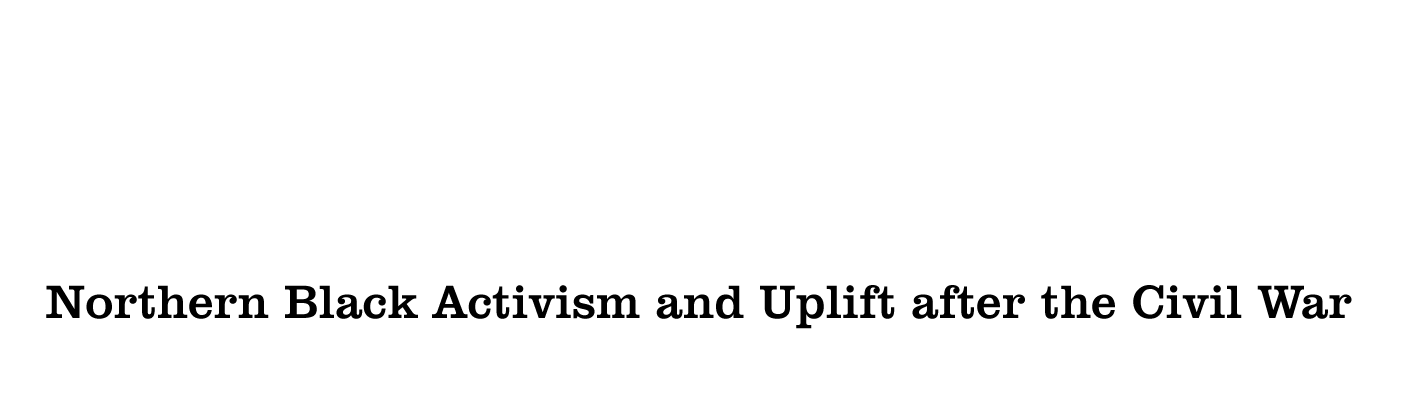

Heroes of the Colored Race. Philadelphia: J. Hoover, 1881.

This print features many of the premier African American statesmen of the era: U. S. Senator Blanche Kelso Bruce of Mississippi; Frederick Douglass, civil rights activist and diplomat; and U. S. Senator Hiram Revels of Mississippi. Typical of these heroic prints, the central figures are surrounded by scenes showing the progress of African Americans from slavery to freedom. As here, in most of these prints black women (if included at all) were usually symbolic types relegated to the margins. Joseph Hoover was among a growing number of lithographers who created products for African American households and selected subjects based on the “tastes of the masses.”

The Colored Beauty. New York: Currier & Ives, 1872.

One of the preeminent lithography firms in the late 19th century, Currier and Ives’s success was based on their talent for producing a variety of lithographs to appeal to a range of markets. A recurring genre of their prints was idealized portraits of women, whose beauty was expressed in their wardrobes, hair styles, and expressions. The Colored Beauty, a rare entry featuring a woman of color, was likely marketed to African American customers. At the same time, Currier and Ives produced Darktown, a profitable series of prints that caricatured African American life.

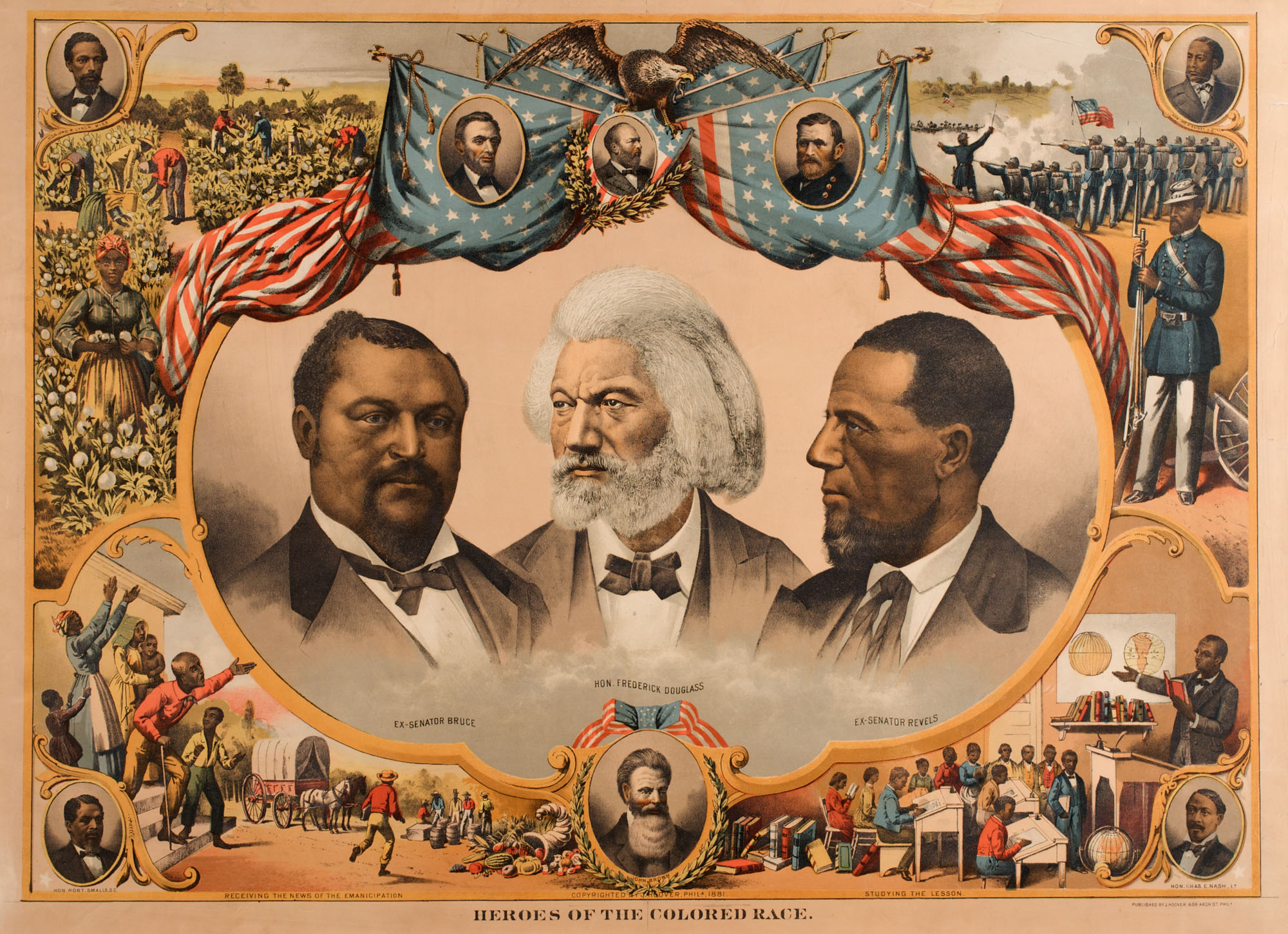

Distinguished Colored Men. Chicago: Geo. F. Cram, 1883.

This lithograph celebrates Northern and Southern black men who served in a variety of leadership positions as politicians, ministers, educators, diplomats, lawyers, and businessmen. The “agents wanted” inscription in the lower-right corner indicates that it was sold by subscription, a practice that lessened the financial risk to the publisher.

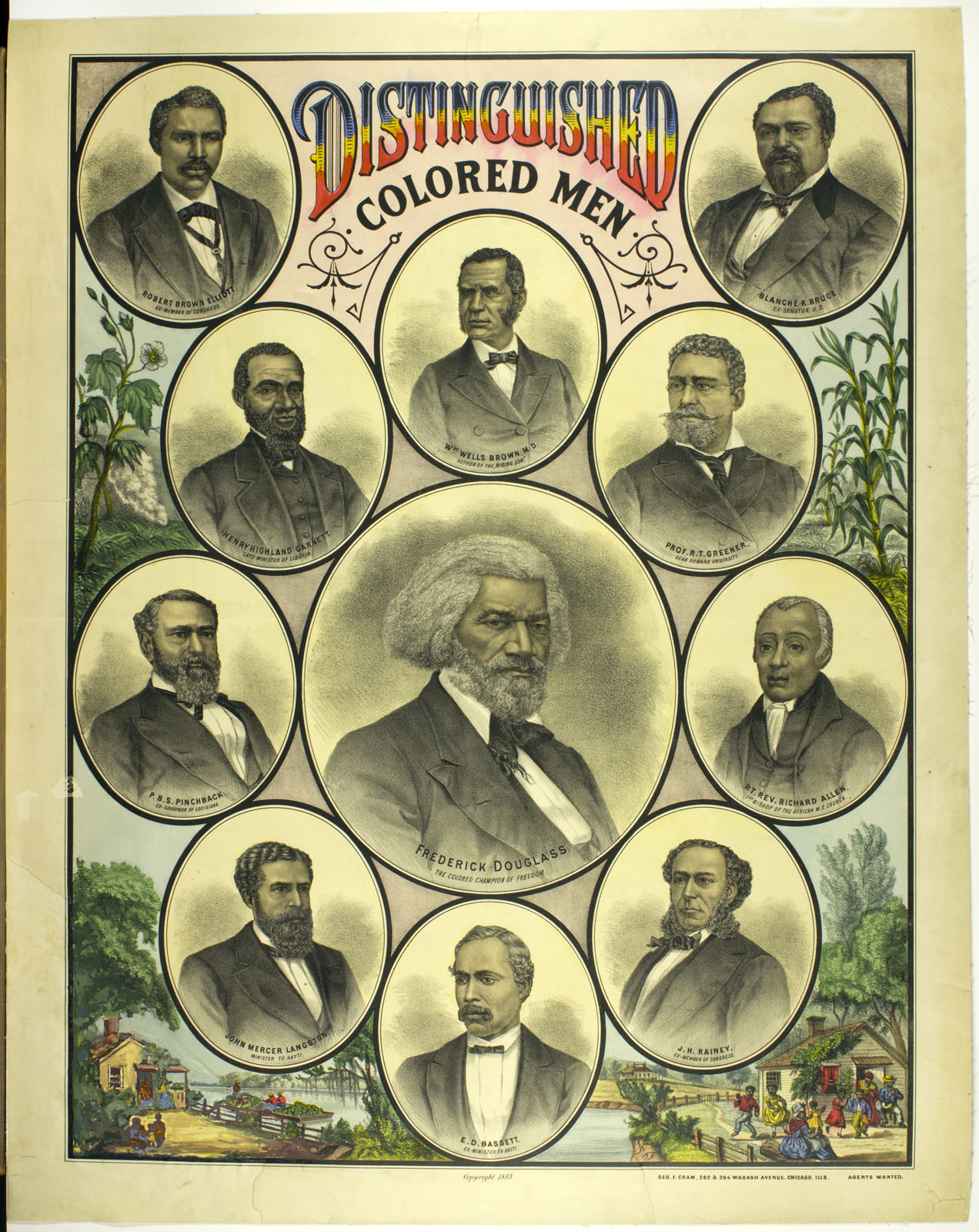

Dixon’s Carburet of Iron Stove Polish. New York: The Major & Knapp Lith. Co., ca. 1885.

Images of African Americans appeared frequently in advertisements in the late 19th century. These images usually cast African Americans in an inferior light as lowly domestic servants or caricatures. In this advertisement, the woman’s dark skin provides a foil to the pallor of the little girl’s body, implying that the stove polish is so effective that it can transform whiteness into blackness.

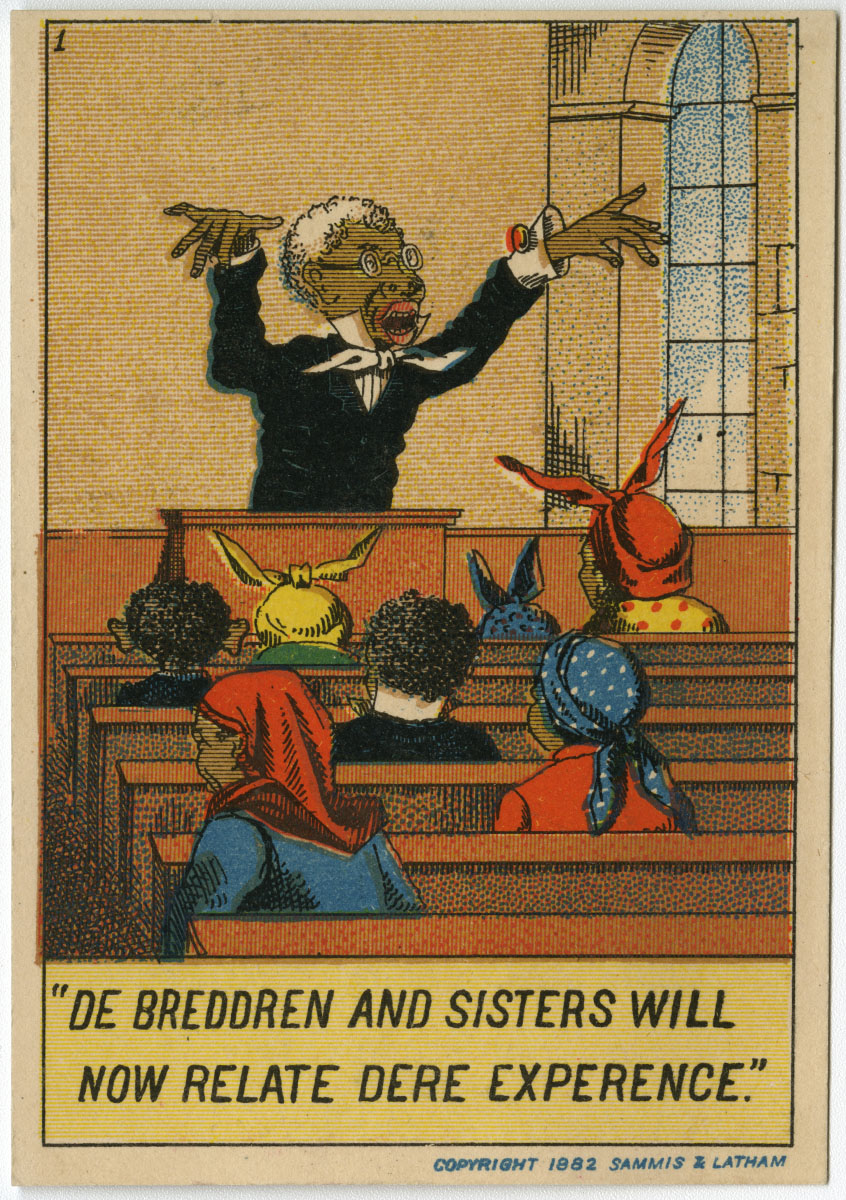

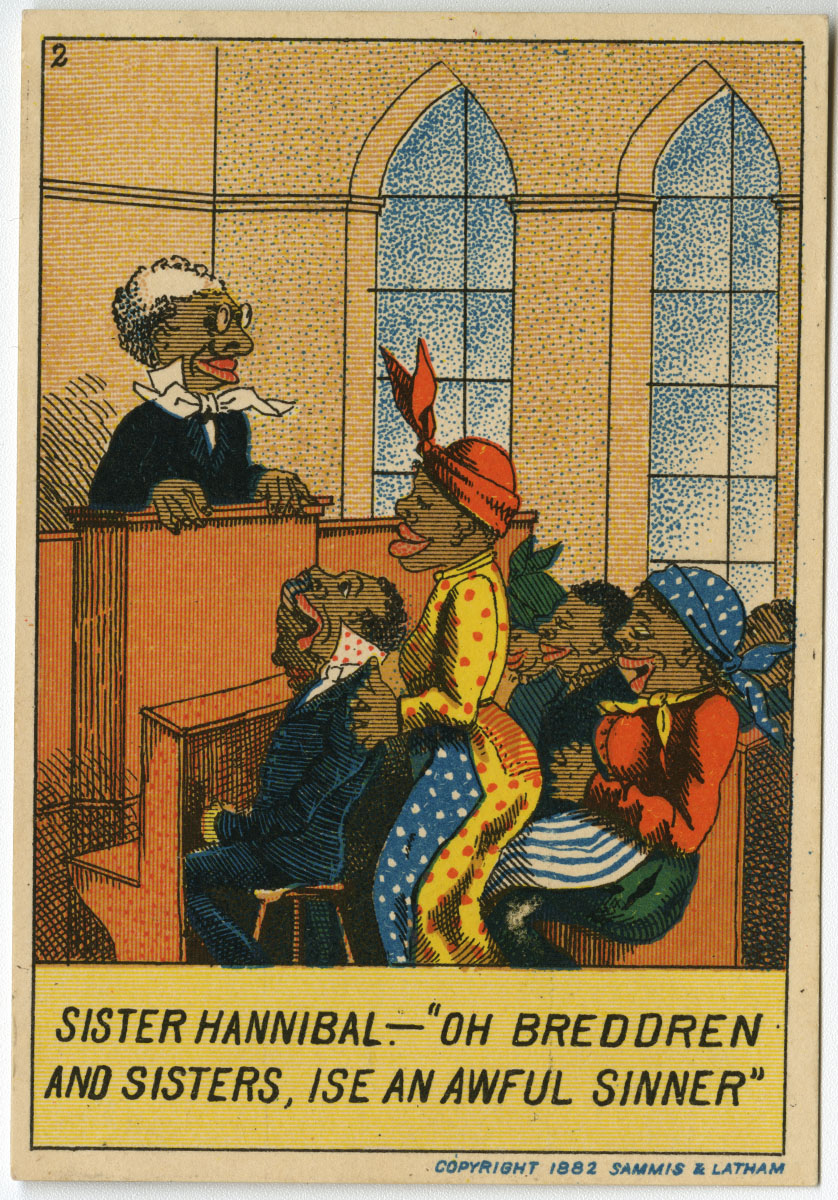

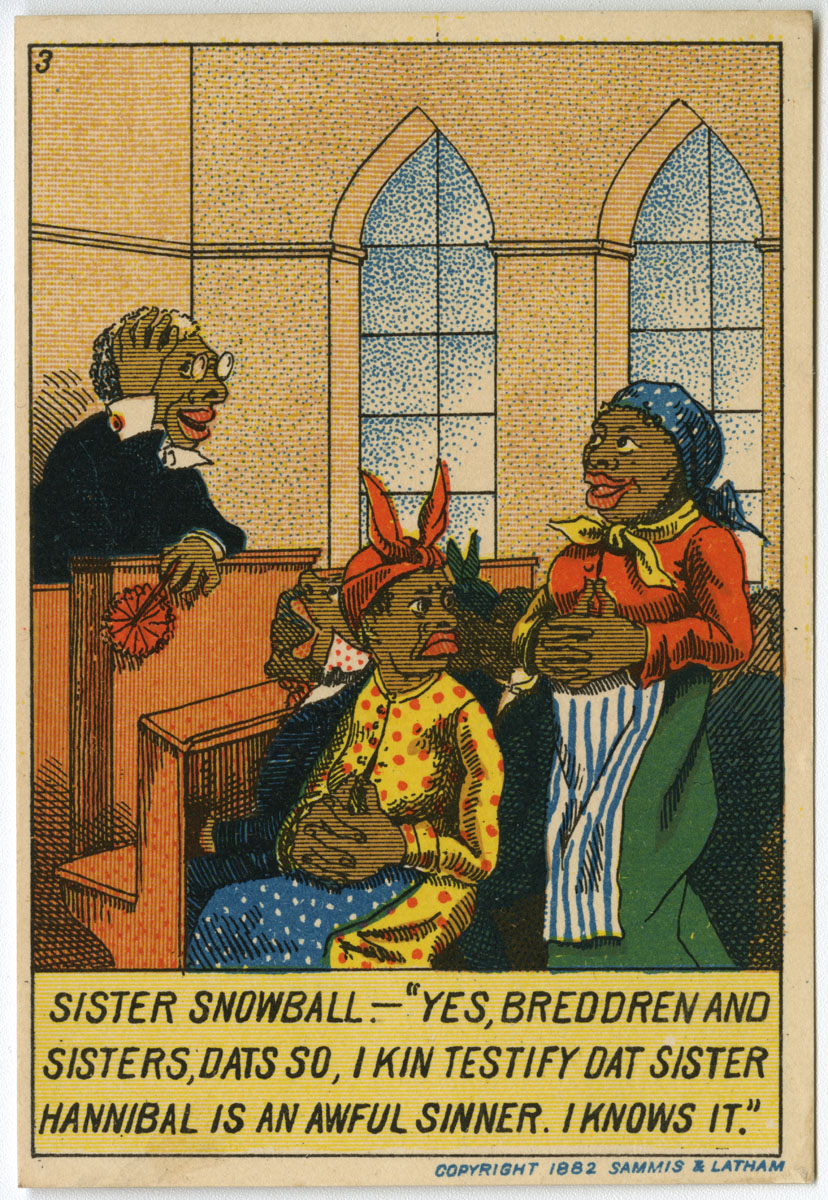

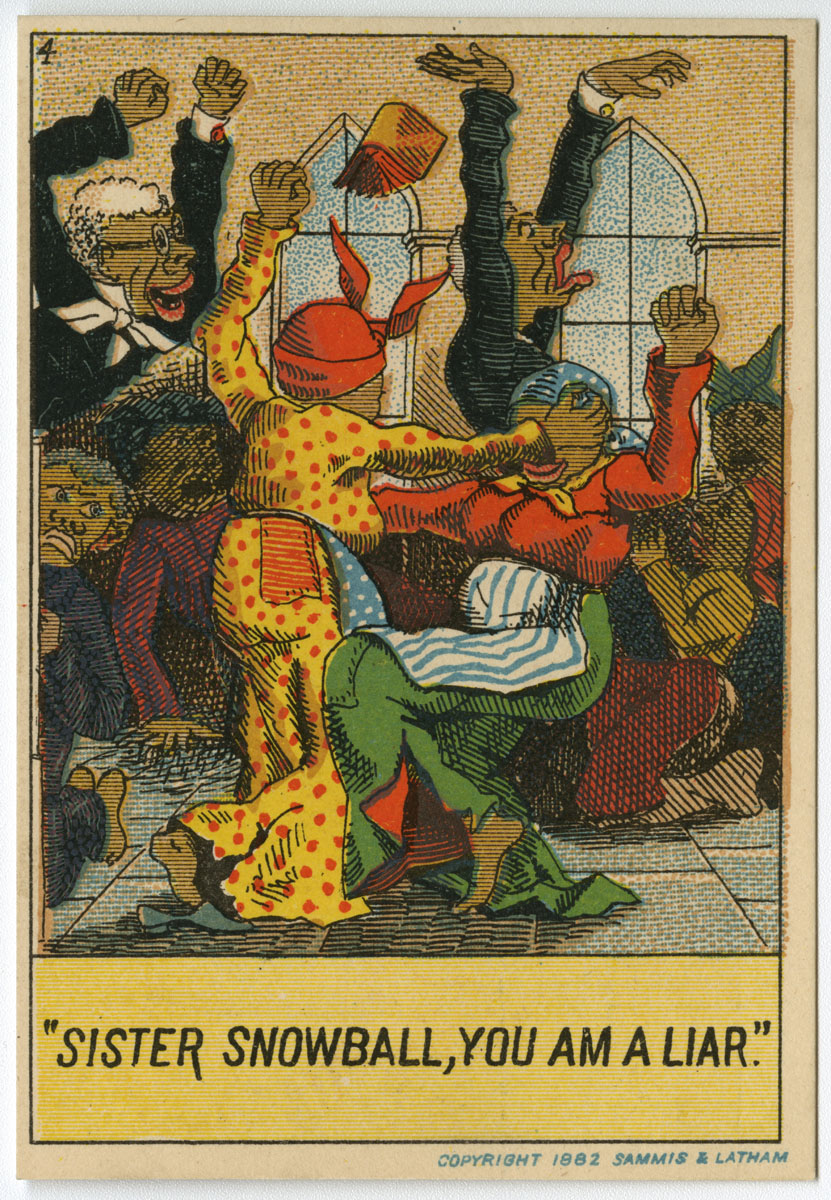

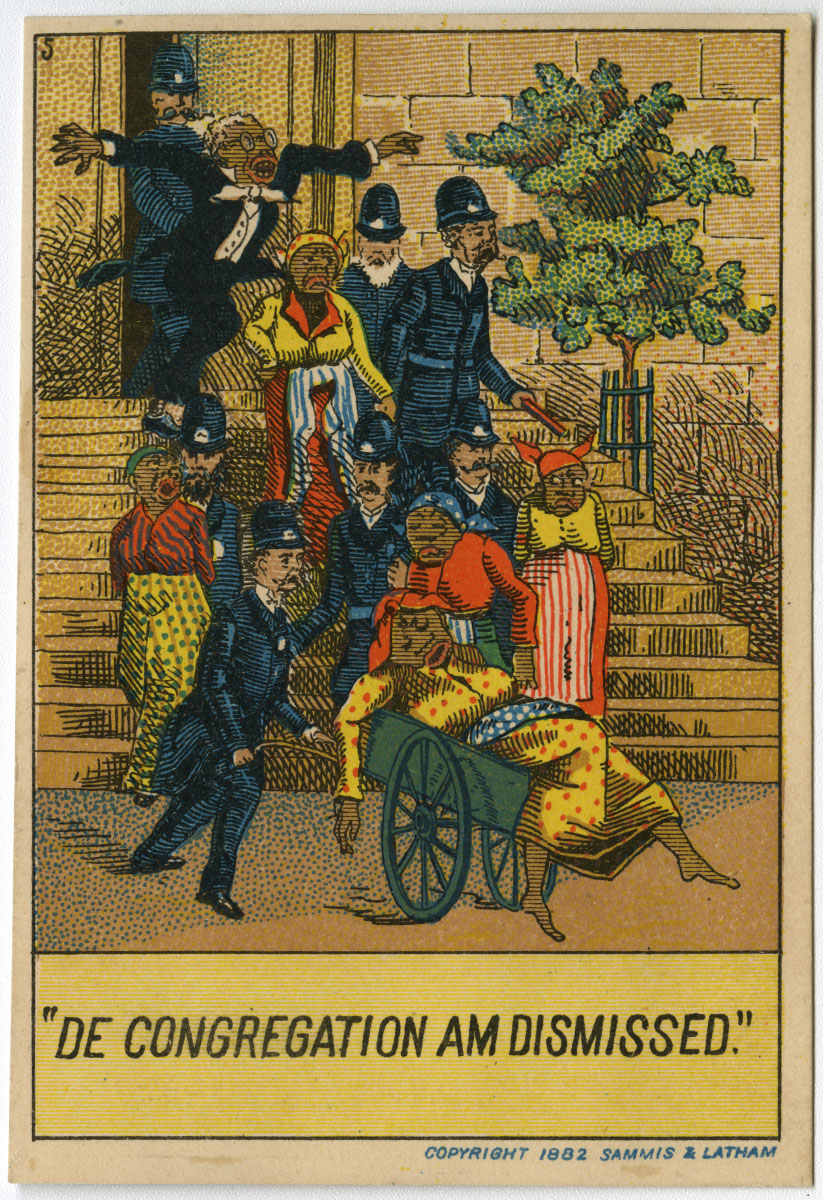

Trade cards. New York: Sammis & Latham, 1882.

Sammis & Latham was a New York publishing firm that issued comic card sets and juvenile novelty items, a common money-making practice of printers and lithographers. The two collecting cards seen here are part of a set of five which uses dialect and exaggerated facial features to caricature African American church life. In this scenario, a religious service descends into a drunken brawl that requires police intervention. In an era when women were considered the civilizing force within their homes, this depiction of two black women fighting further suggests that African Americans could not be respectable members of society.

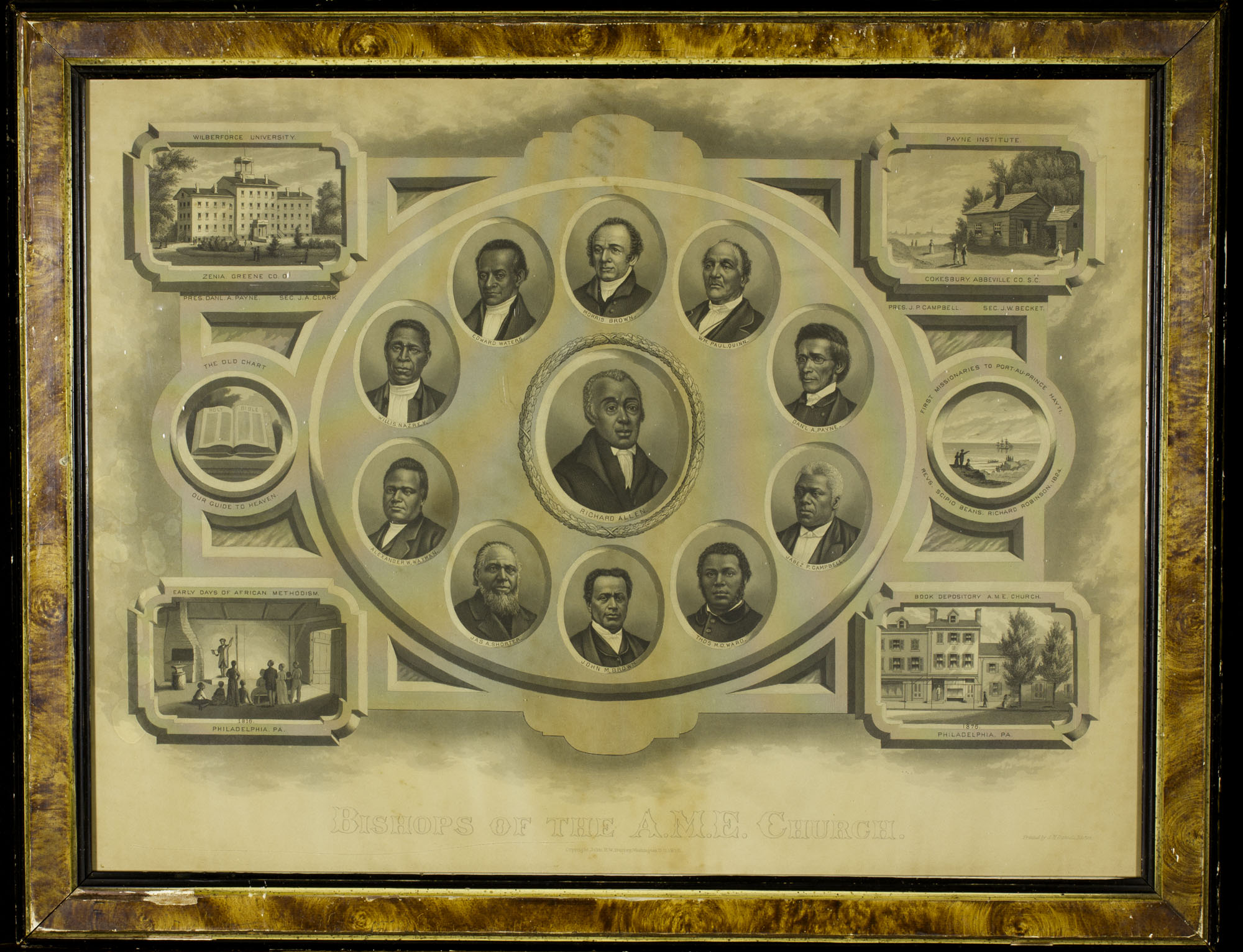

Bishops of the AME Church. Boston: J.H. Daniels, 1876. Gift of Roger Stoddard.

In 1794, Philadelphian Richard Allen founded the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, which was the first independent black church denomination in the United States. The church frequently commissioned printed works, from church histories to lithographs, to help spread its message and to provide examples of proper religious and social behavior. This print was commissioned in commemoration of America’s centennial, thus inserting the church and black Americans into the narrative of the nation’s development. The print’s six vignettes depict important events, sites, and symbols in the church’s history.

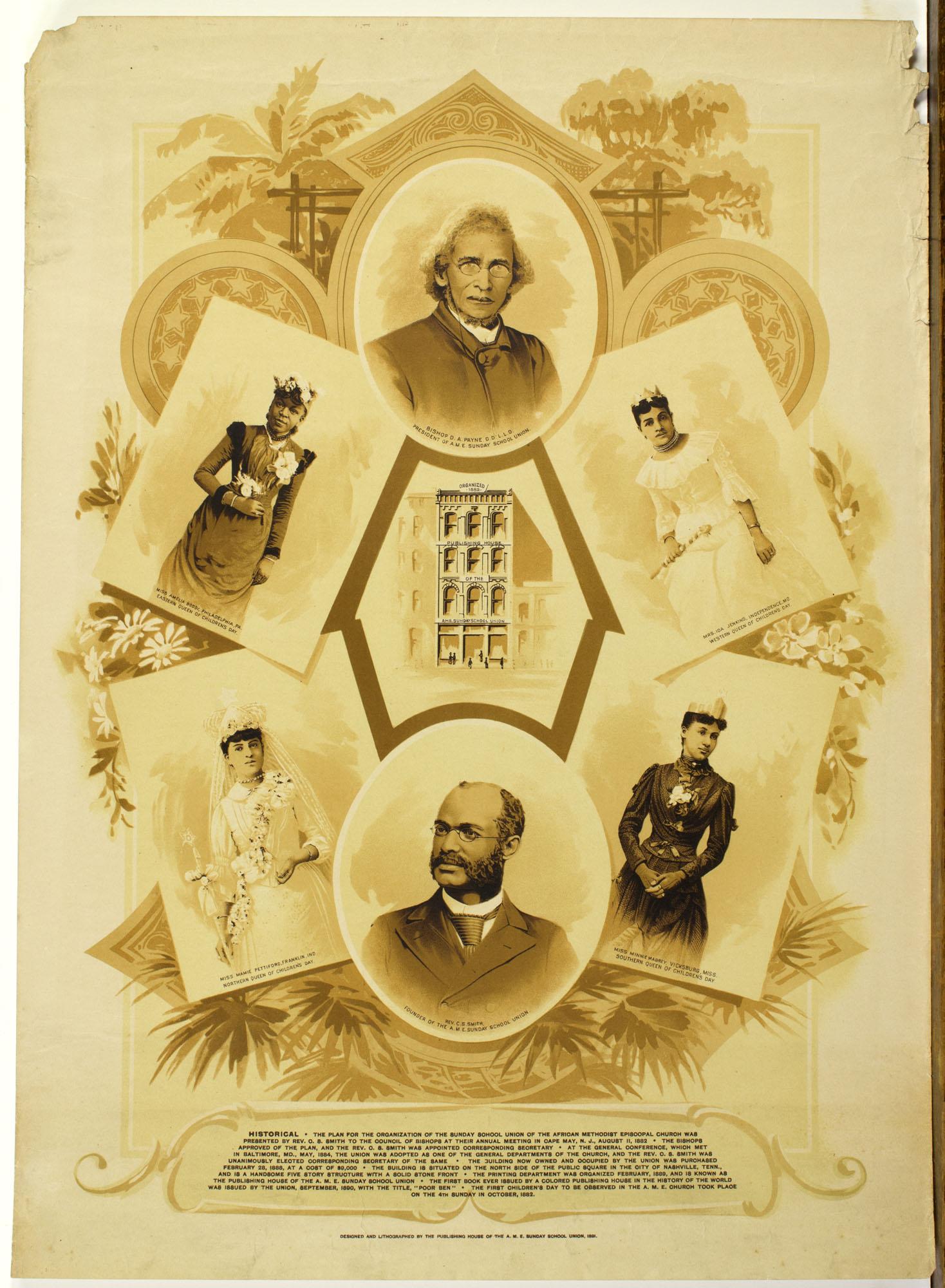

Children’s Day lithograph. Nashville: AME Sunday School Union, 1891.

The AME Sunday School Union was founded in 1882 by Charles S. Smith, who is featured in one of the vignettes. This lithograph celebrates Children’s Day, a fundraising event when Sunday school students donated small sums of money to support the Sunday School Union. While the AME Church was headquartered in Philadelphia, Nashville was chosen as the site for the new publishing arm, being well situated to disseminate material to the recently freed people of the South and to westbound settlers founding churches in new territories of the United States. Despite the shift of operations, African Americans in the North still sought out the church’s symbolic representations of black uplift. Absalom Arter, a resident of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, purchased this print.

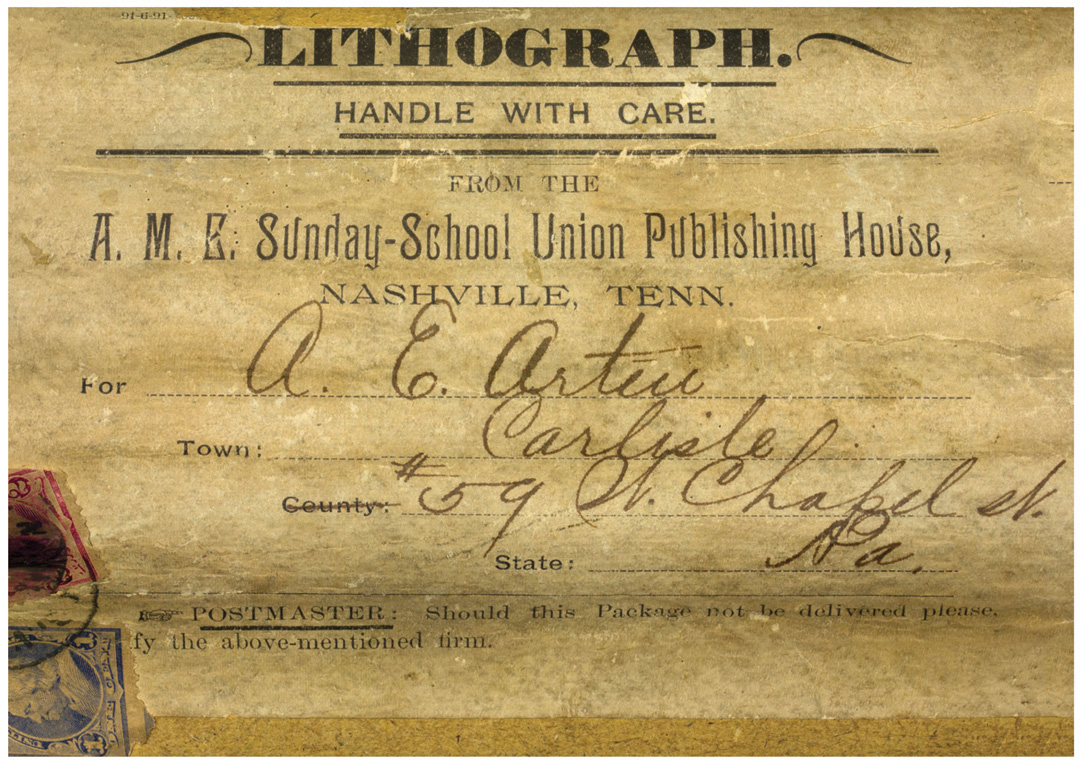

AME Sunday School Union mailer tube. Nashville: AME Sunday School Union, 1891.

The AME Sunday School Union lithograph displayed above was sent to Absalom Arter in this mailer tube. Born in Virginia, Arter (1839-1923) served in the U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War. Working as a laborer and gardener, he lived in various places in western and central Pennsylvania, including Carlisle. He had at least four children with his wife Henrietta. At the time that he purchased this print, he was well into middle-age and married to his third wife Ellen, with whom he eventually had ten children. Although the Arters were not wealthy and probably lived in tight quarters, they likely displayed this print prominently in their main living room.

Portrait of Johnson al-Jube, ca. 1870, in Portrait Album of Well Known [19th-century African American Men of Philadelphia].

This photographic portrait was included in an album featuring 18 black Philadelphian men from a variety of occupations, including a janitor, musicians, and barbers. Although it is not known who compiled the album or when, each portrait was labelled with the sitter’s name. Little is known about Johnson al-Jube. He wears modest, ill-fitting clothing and carries a basket, which likely signifies that he was a peddler. Despite his low status occupation, Al-Jube’s inclusion in this album, which may have been displayed in the owner’s parlor, indicates that he was of some renown in black Philadelphia.

Portrait of Taylor Aldridge, 1883, in Portrait Album of Well Known [19th-century African American Men of Philadelphia].

Taylor Aldridge was a waiter and caterer, both of which were well-paid, respectable trades for black men during the 19th century. In 1886, a few years after this portrait was taken, Aldridge was living at 1231 Locust Street, only one block from here. Aldridge’s pocket watch and ring indicate that he had achieved a level of prosperity. Toward the end of the century, opportunities for black men in the food industry, as waiters, caterers, and bakers, declined due to competition from European immigrants and an increase in large-scale catering businesses.