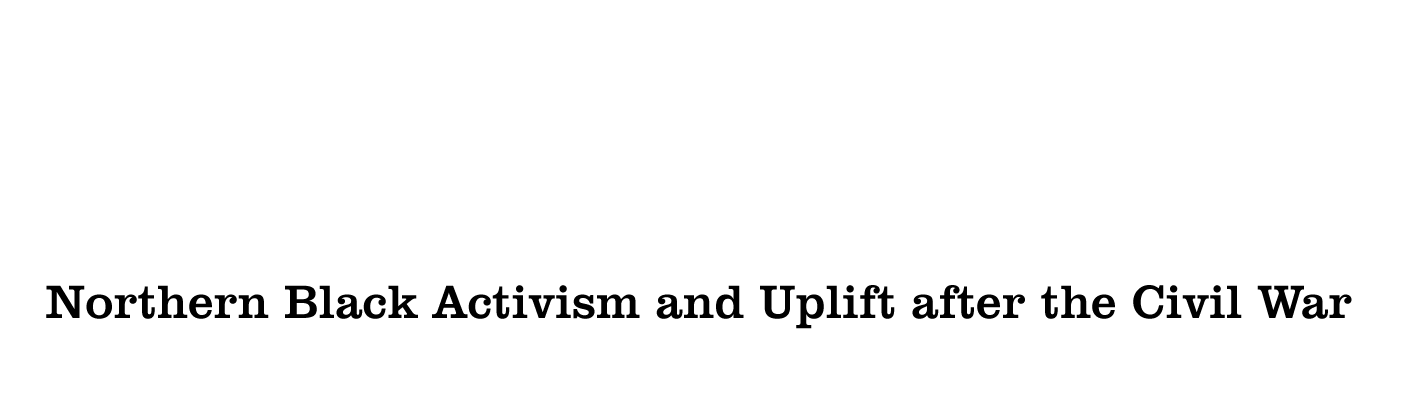

Constitution of the American Society of Free Persons of Colour, for Improving Their Condition in the United States. Philadelphia: J. W. Allen, 1831.

African Americans held their first large-scale convention in 1830 when forty delegates congregated in Philadelphia to consider the future of the race. The meeting was partly precipitated by events in Ohio, where the state’s courts had reaffirmed racially discriminatory laws and mobs had expelled black residents from the state. The convention led to the formation of the American Society of Free Persons of Colour, whose constitution is displayed here. The Society was intended to function as the parent organization of state and regional auxiliaries that would coordinate civil rights activities locally.

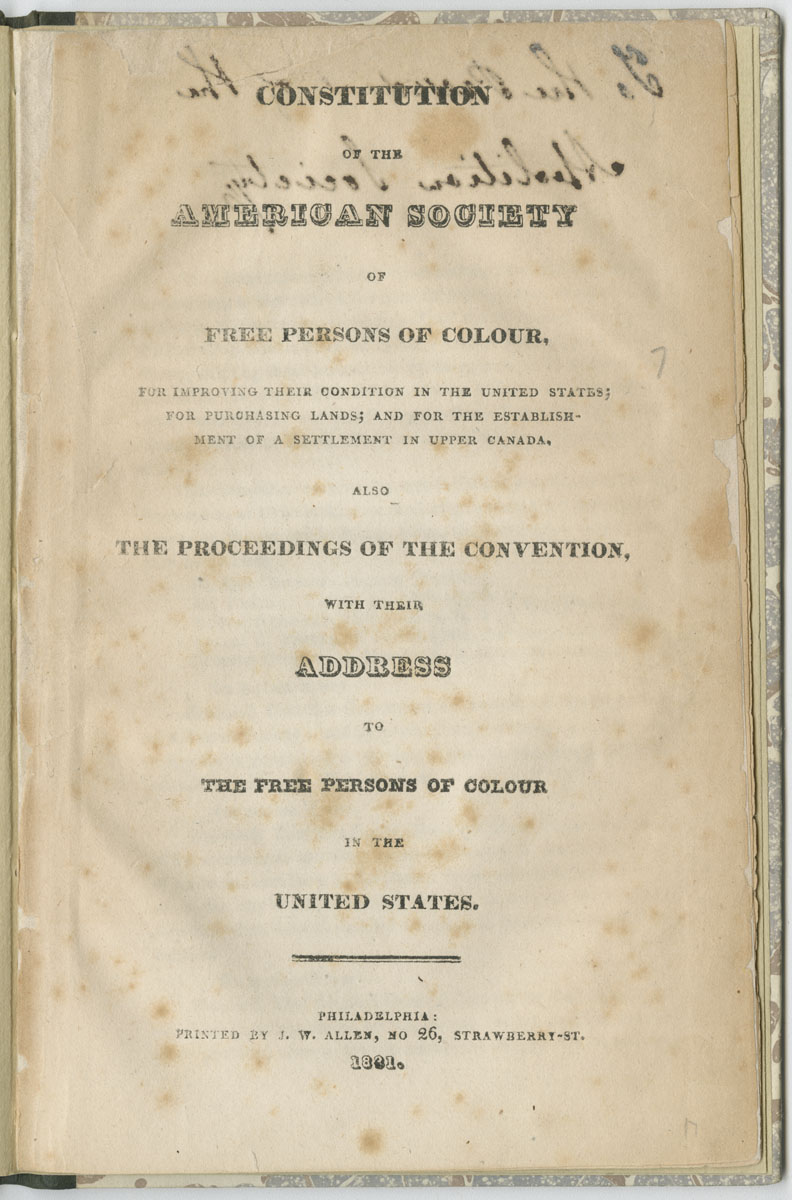

Proceedings of the National Convention of Colored Men, Held in the City of Syracuse, NY, October 4, 5, 6, and 7, 1864. 1864. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

One hundred and forty-four delegates from 18 states convened in Syracuse in October 1864. Black Tennesseans sent two delegates to learn from their Northern counterparts in anticipation of holding a state convention. The most significant accomplishment of the Syracuse convention was the establishment of the National Equal Rights League, an organization that would create a unified agenda for civil rights activism in both the North and the South. The convention stressed racial solidarity, resolving that “we extend the right hand of fellowship to the freedmen of the South, and … we desire further, to assure them of our co-operation and assistance.”

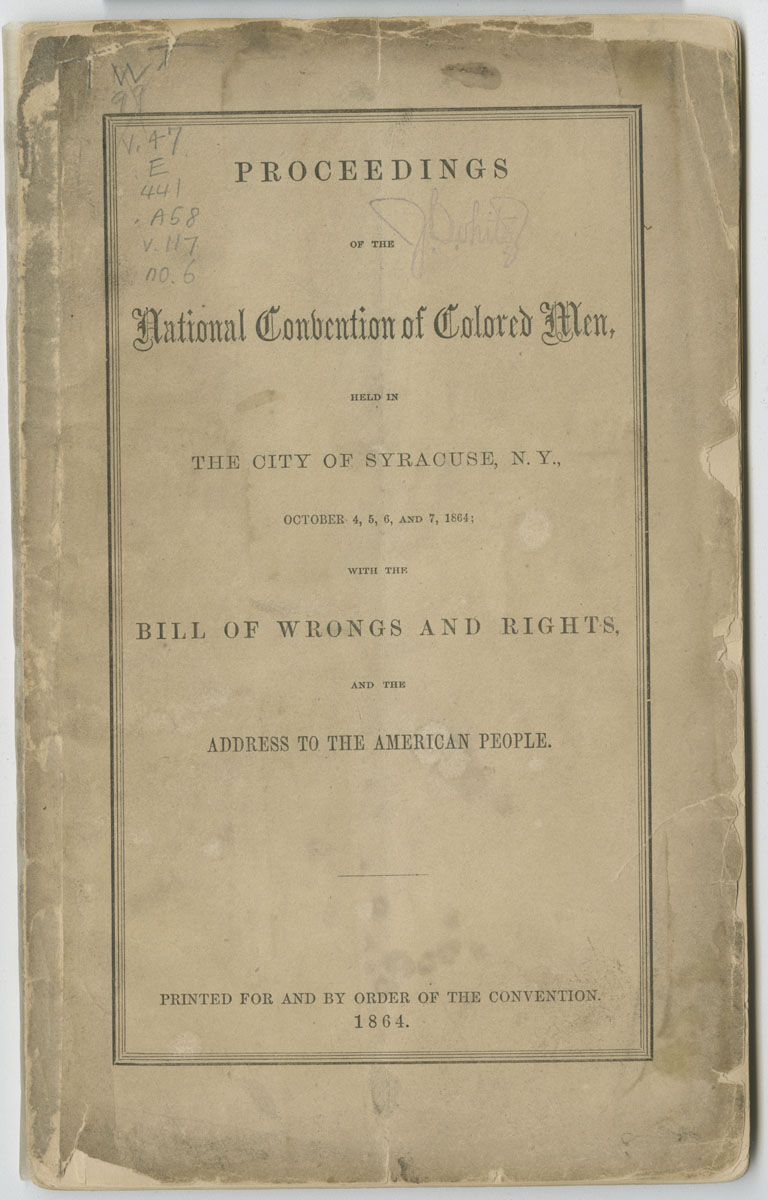

“Declaration of Wrongs and Rights” in Proceedings of the National Convention of Colored Men, Held in the City of Syracuse, NY, October 4, 5, 6, and 7, 1864. 1864. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

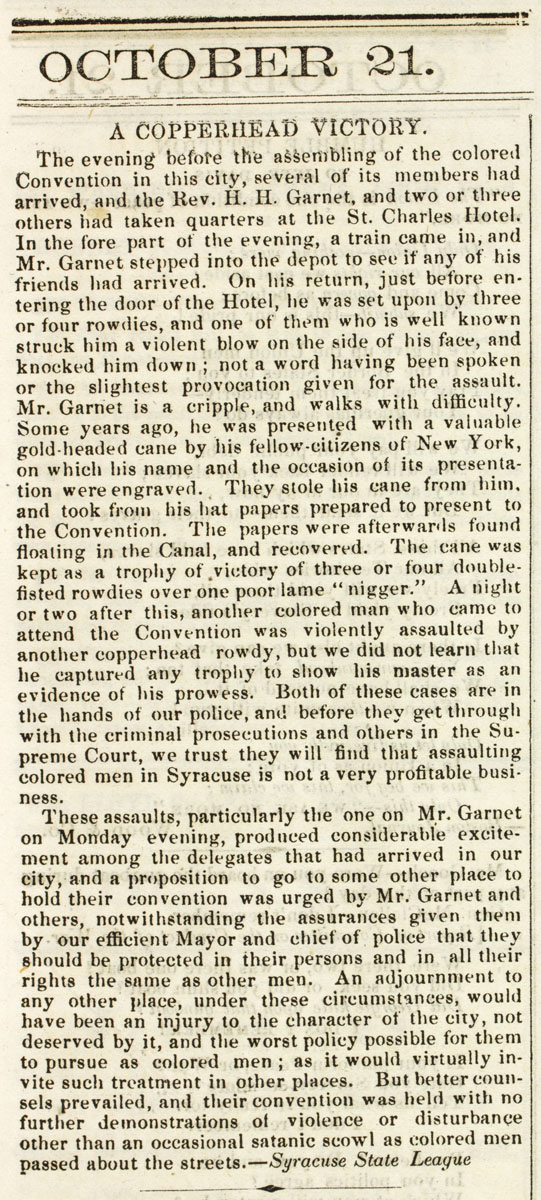

“A Copperhead Victory.” The Liberator (October 21, 1864).

Free blacks in the North remained targets of violence by white Northerners who believed in black inferiority or sympathized with the Confederacy. Black politicking, in particular, aroused hostility from this group. As described in this article, Henry Highland Garnet, who walked with a cane due to an amputated leg, was the victim of a racially motivated attack while in Syracuse for the convention. During his address to the convention, Frederick Douglass also noted overhearing people on the street asking, “Where are the d–d niggers going?” in response to the increased numbers of African Americans in town.

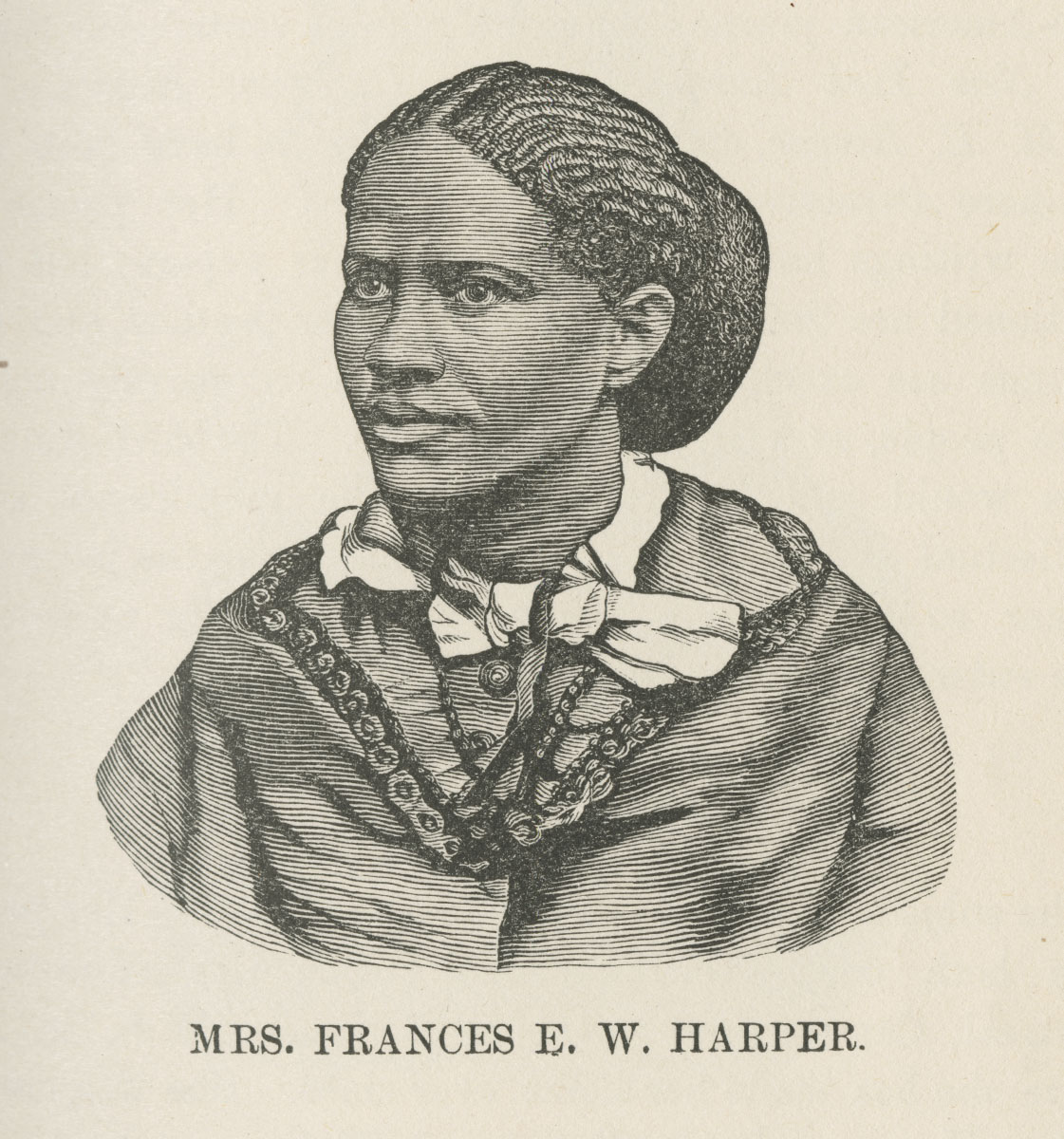

Portrait of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper from The Afro-American Press and Its Editors. Springfield, MA.: Willey & Co., 1891.

With few exceptions, the antebellum colored conventions were restricted to male delegates and speakers. Unusually, two women, teacher Edmonia Highgate (1844-1870) and abolitionist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-1911), were held in such high regard that they were permitted to address the Syracuse convention. Nevertheless, their remarks were not recorded for the proceedings, likely a reflection of the era’s marginalization of women.

Despite their absence from most pre-Civil War conventions, black women contributed in other ways, such as raising funds to sponsor convention travel and registration fees for male delegates. In some places, women were allowed to vote for the delegates who would represent their communities at the state or national level.

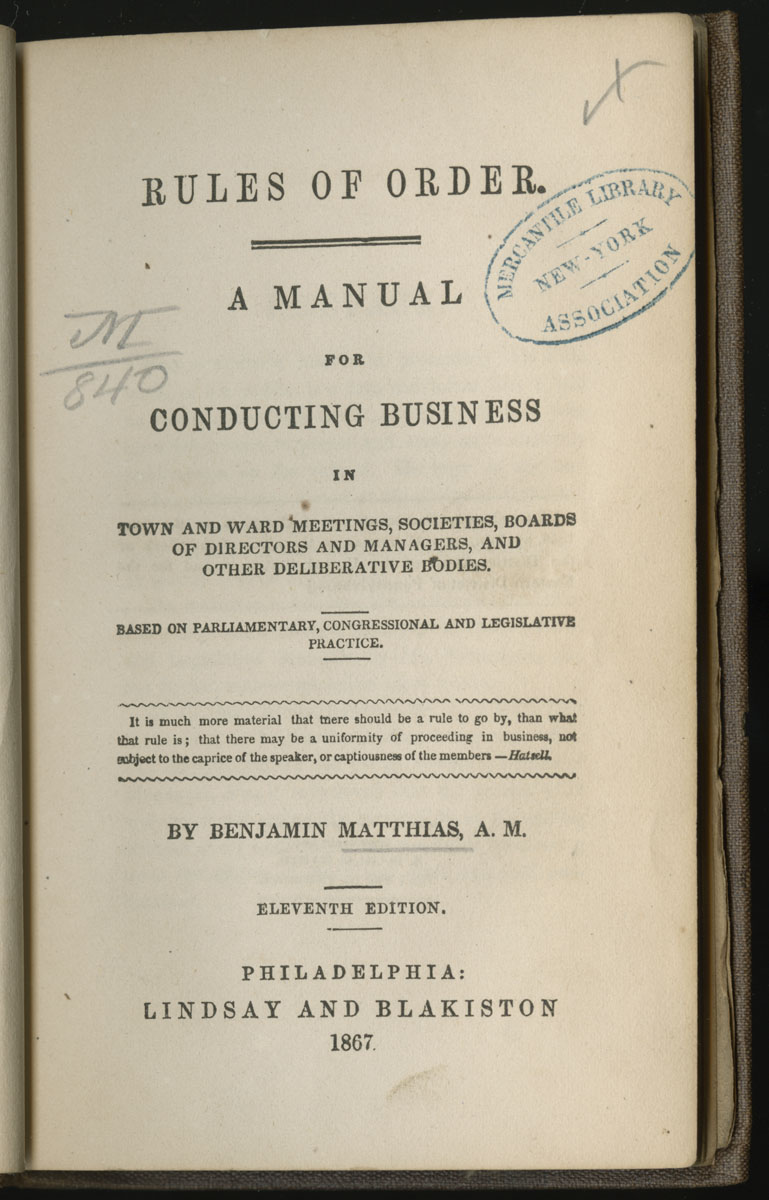

Benjamin Matthias. Rules of Order: A Manual for Conducting Business in Town and Ward Meetings, Societies, Boards of Directors and Managers, and Other Deliberative Bodies. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1867.

Colored conventions were formal events, requiring delegates to present credentials to show that they were rightfully elected or appointed by their local constituencies. In addition, delegates selected a standard for rules of order to govern the conventions, such as recognizing who held control of the floor and authenticating the proposal and passage of resolutions. For the Syracuse convention, Matthias’s Rules of Order was selected. The 1867 edition is shown here.

Jason T. Fields. Rally Round the Flag. Boston: Oliver Ditson & Co., 1862. Gift of Clarence Wolf.

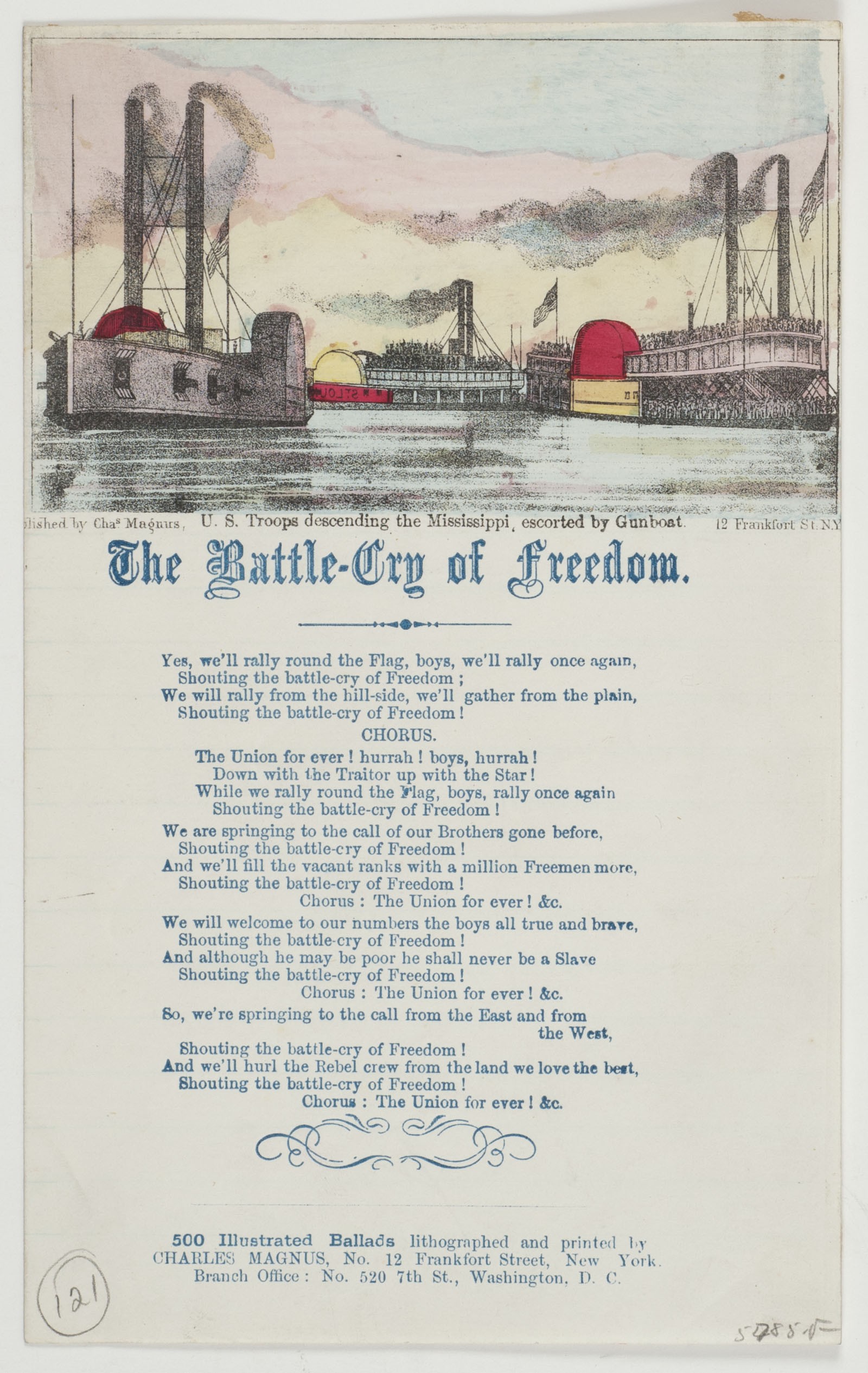

Battle-Cry of Freedom. New York: Charles Magnus, circa 1860.

Rituals helped build esprit de corps among colored convention delegates. Each day began with a prayer, and sessions often began or ended with a delegate leading the entire body in patriotic song. The songs seen here are among those sung at the Syracuse convention.

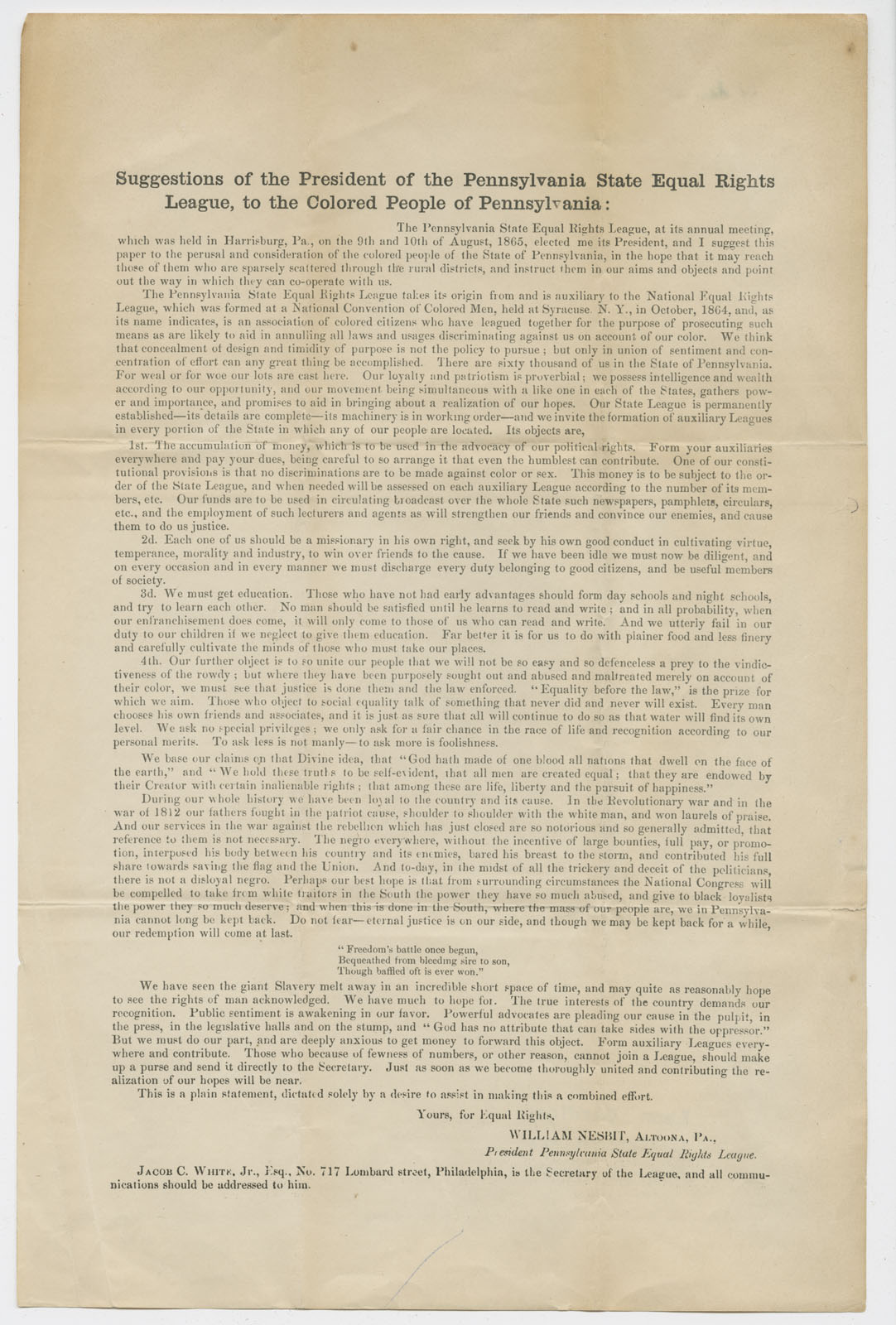

William Nesbit. Suggestions of the President of the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League, to the Colored People of Pennsylvania. Altoona, PA, 1865. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

The Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League was a state chapter of the National Equal Rights League, whose objectives included securing political rights, supporting education, and protecting blacks from racial prejudice and violence. In this address to promote the state league, president William Nesbit traced the lineage of the organization back to the Syracuse Convention. While he noted the importance of funding the League’s work through membership dues, he cautioned chapter leaders to keep the dues affordable in order to garner the broadest possible participation from the black community. Nesbit took to the road to help new auxiliaries form, and, by early 1866, forty-three had been established throughout the state.

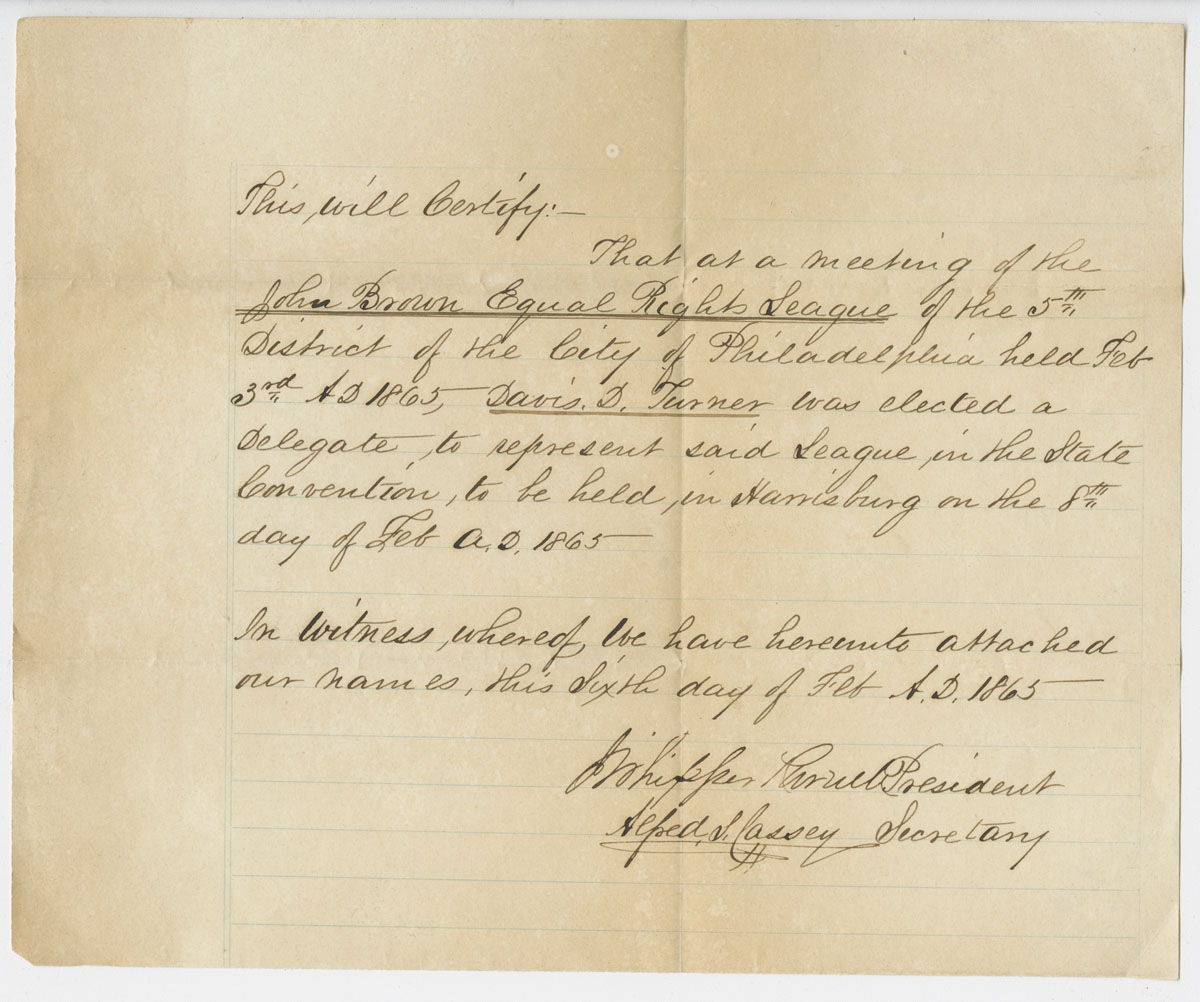

James Purnell. This Will Certify: That at a Meeting of the John Brown Equal Rights League. Altoona, PA, 1865. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

This note certifies the election of a delegate to represent black Philadelphians at the state convention of the Pennsylvania Equal Rights League. Such a note would comprise part of a delegate’s credentials package. The name of this local chapter suggests the high regard that Northern African Americans still held for abolitionist John Brown, who was executed after attempting to instigate a slave rebellion at Harpers Ferry.

Proceedings of the First Annual Meeting of the National Equal Rights League, Held in Cleveland, Ohio, October 19, 20, and 21, 1865. Philadelphia: Markley & Son, 1865.

When the National Equal Rights League convened its first meeting, the Thirteenth Amendment, the constitutional amendment abolishing slavery, was still being debated by the states. Of the forty-one delegates, only eight were from Southern states. Nevertheless, in anticipation of the amendment’s ratification, the members of the League prioritized the civil rights issues which would comprise the national agenda. However, the proceedings reveal tensions within the black community. League President John M. Langston “earnestly exhorted all colored men to regard each other in a civil and just manner” and denounced the racial discrimination of black barbers, restaurateurs, and waiters, who chose to limit their clientele to white customers for economic reasons.

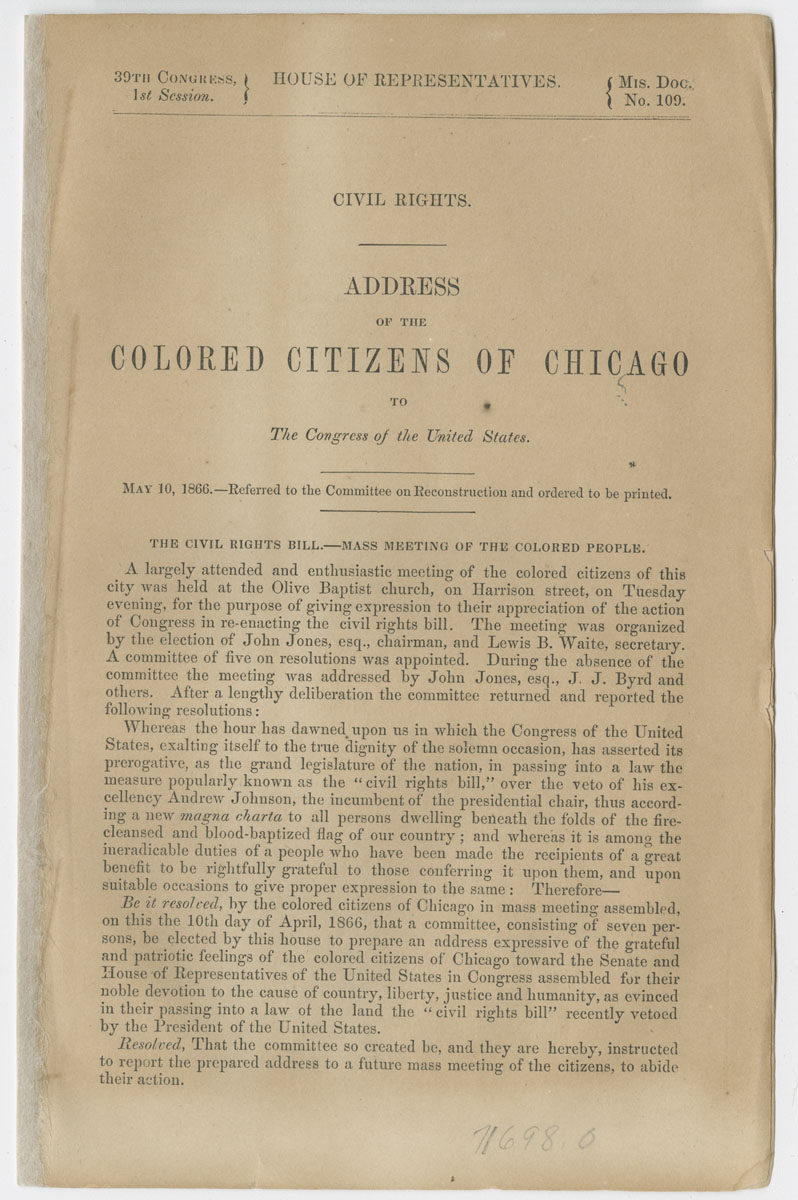

Civil Rights: Address of the Colored Citizens of Chicago to the Congress of the United States, May 10, 1866. Washington, DC, 1866.

Although formally organized conventions were important forums for raising civil rights issues, smaller bodies also made their voices heard, as in the case of this address which was included in the Congressional record. Black Chicagoans praised Congress for overturning President Andrew Johnson’s veto to pass the 1866 Civil Rights Act, which gave citizenship and other rights to people born in the United States without regard to race, color, or previous condition of slavery. Presiding over this Chicago meeting was John Jones, an experienced lobbyist against Black Codes, who understood the importance of commending lawmakers in order to encourage future support for civil rights legislation.

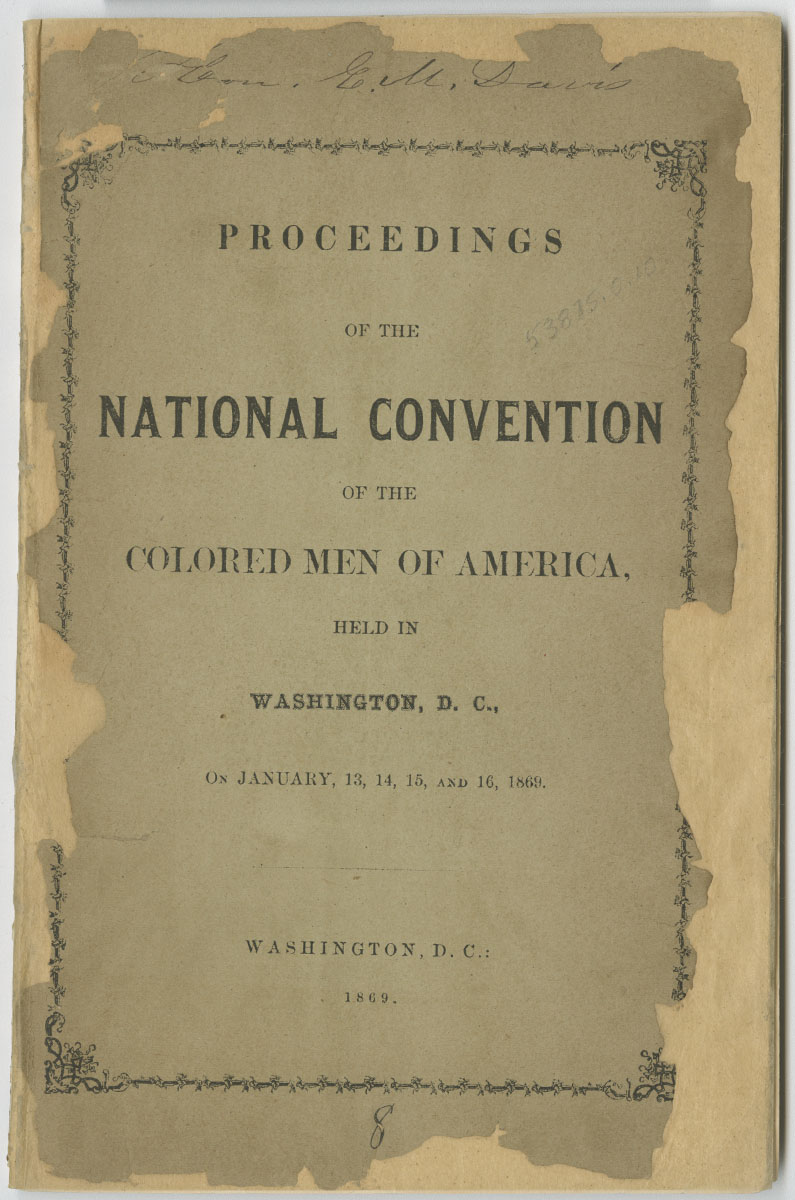

Proceedings of the National Convention of the Colored Men of America: Held in Washington, DC, on January 13, 14, 15, and 16, 1869. Washington, DC: Great Republic Book and Newspaper Printing Establishment, 1869.

Pennsylvania delegates dominated the offices of a convention held in Washington, DC, in 1869. One of the primary concerns of this convention was that the Fourteenth Amendment had not guaranteed all civil rights for African Americans, particularly the right to vote. The convention created a standing National Executive Committee, based in Washington, DC, whose charge included petitioning Congress to pass an amendment supporting black suffrage, campaigning against racial prejudice, and supporting educational opportunities for African Americans. Auxiliary committees in each state would support the executive committee through funding as well as grassroots organizing efforts.

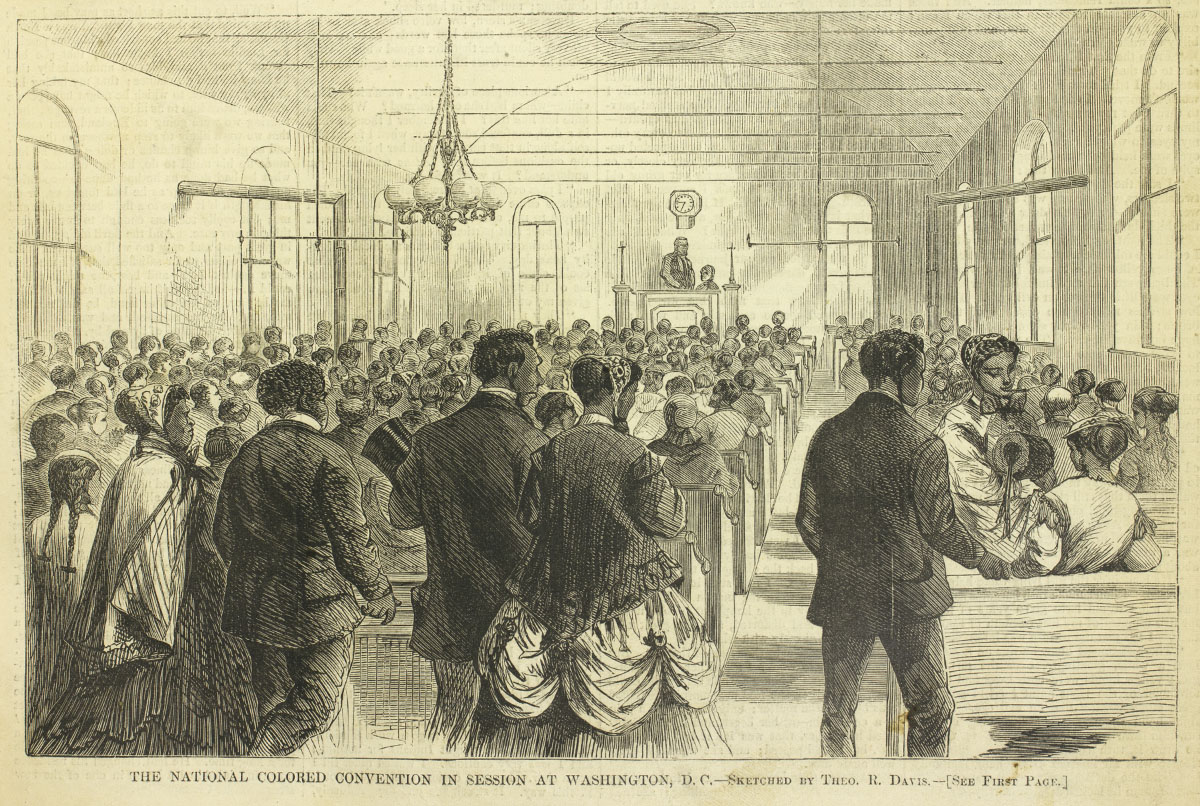

“The National Colored Convention in Session at Washington, DC.” Harper’s Weekly (February 6, 1869).

The acceptance of women delegates and speakers continued to be an issue during conventions. One delegate at the Washington, DC, convention noted that he owed his election to the convention to fifty Philadelphia ladies. Drawing connections between racial and gender discrimination, a motion to admit women was finally carried because “to exclude them from seats in this Convention would be too much like the actions of the occupants of the White House, who had excluded the colored race for two hundred years.”

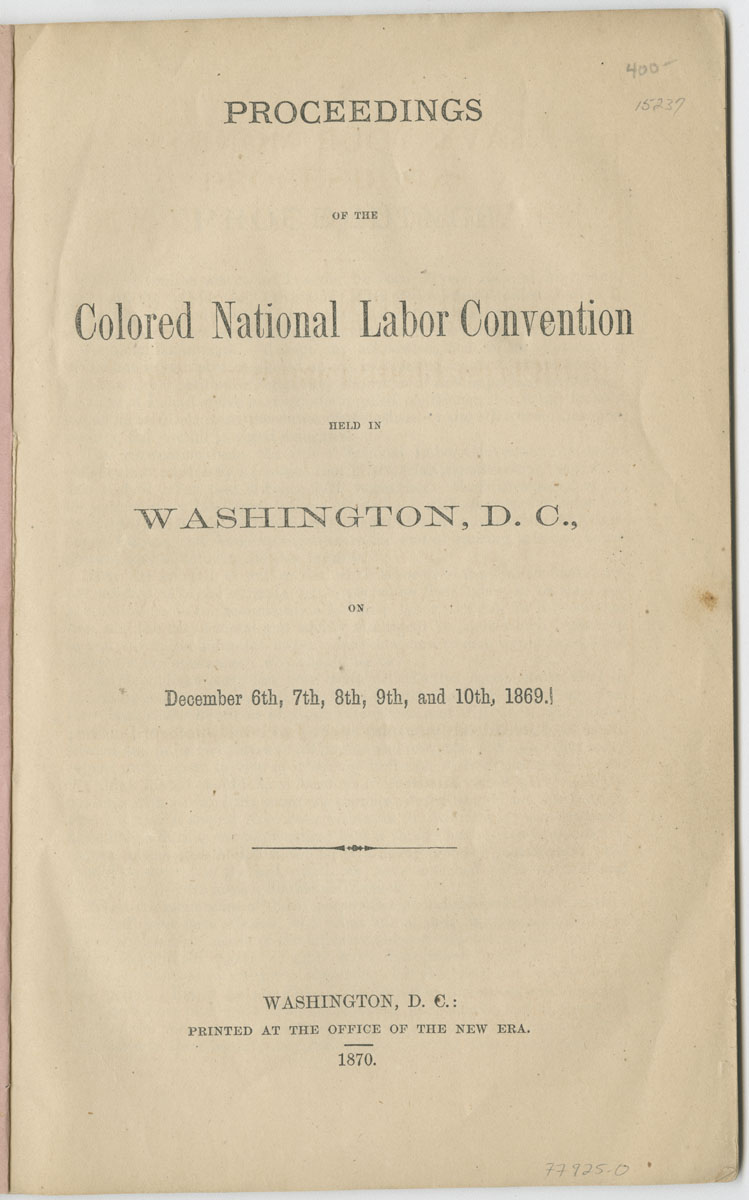

Proceedings of the Colored National Labor Convention: Held in Washington, DC, on December 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th, 1869. Washington, DC: Printed at the Office of the New Era, 1870.

Southerner Isaac Myers and Northerner George T. Downing convened this meeting to organize black labor from a variety of occupations. Attendees documented incidents of prejudice and exclusion in trades such as printing and engineering. Mrs. M. A. S. Carey addressed women’s labor issues, speaking about the lack of positions available to black women beyond teaching and domestic service. Delegates approved her report, which recommended broadening employment opportunities for women in entrepreneurial occupations. The convention led to the creation of the National Labor Union, which hoped to consolidate labor advocacy through interracial labor alliances but collapsed in 1872 due to opposition from other labor unions.

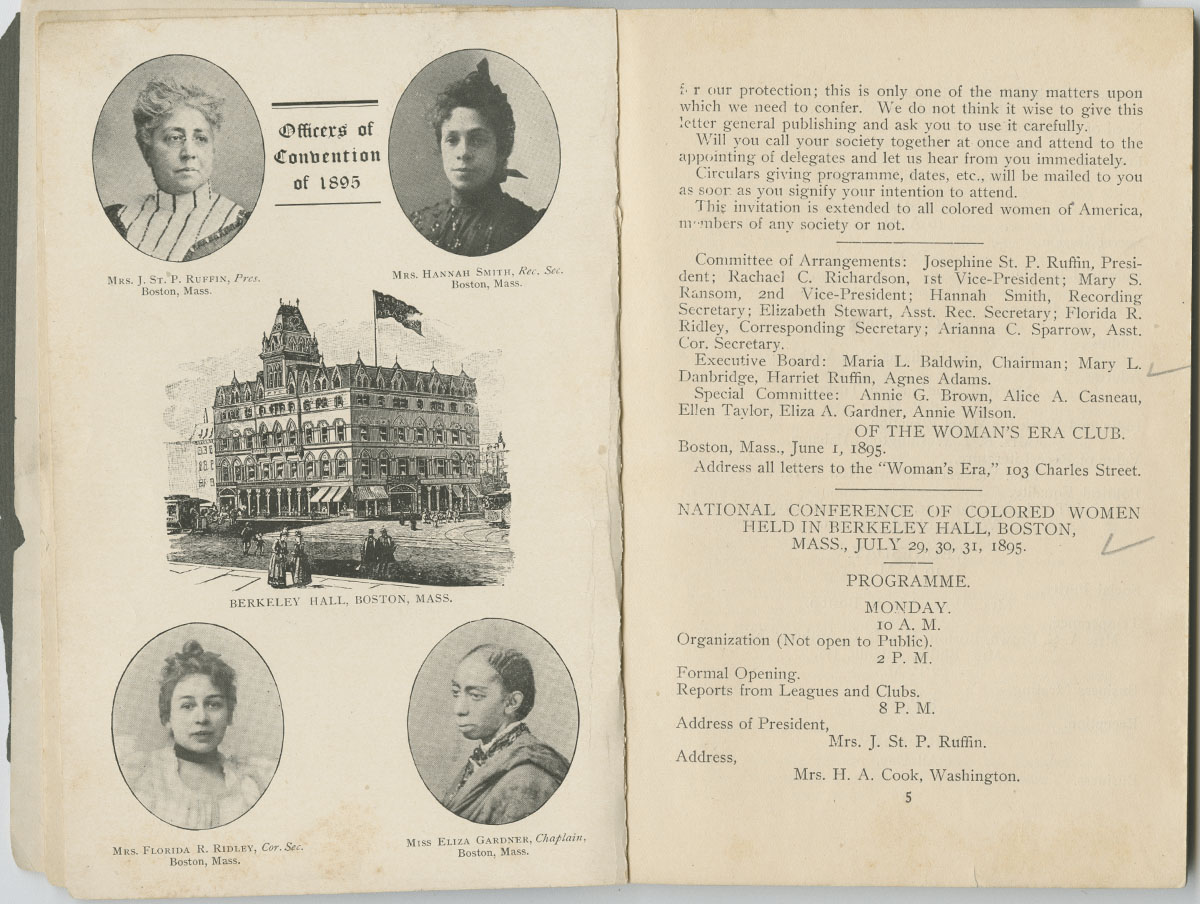

National Association of Colored Women. A History of the Club Movement among the Colored Women of the United States of America. 1902.

Black women continued to be shut out of most national forums for political debate and discussion. In 1895, they formed their own organization, a federation of women’s clubs already in existence around the country. Much of the early leadership at the national level was drawn from the North. At the first meetings featured in this history, convention delegates adopted resolutions on issues including expanding temperance campaigns and petitioning against lynching laws, railroad car segregation, and convict leasing.