Most early historical works by black authors were biographies or autobiographies, which usually described a few exemplars of the race to counterbalance the omission or denigration of blacks in many white-authored works. The late 19th century saw the emergence of a new black historiography devoted to demonstrating that contributions by African American individuals and groups were essential to the course of American history and culture. African American historians conducted extensive primary source research to support their historical analyses. Other writers compiled long encyclopedic works, often delving into subfields such as religion, music, and journalism. Despite being further removed from slavery, Northern black leaders and parents affirmed the need for these historical works in promoting racial uplift in their communities. Greater access to education and publishing resources put Northern black writers at the forefront of the new historiography.

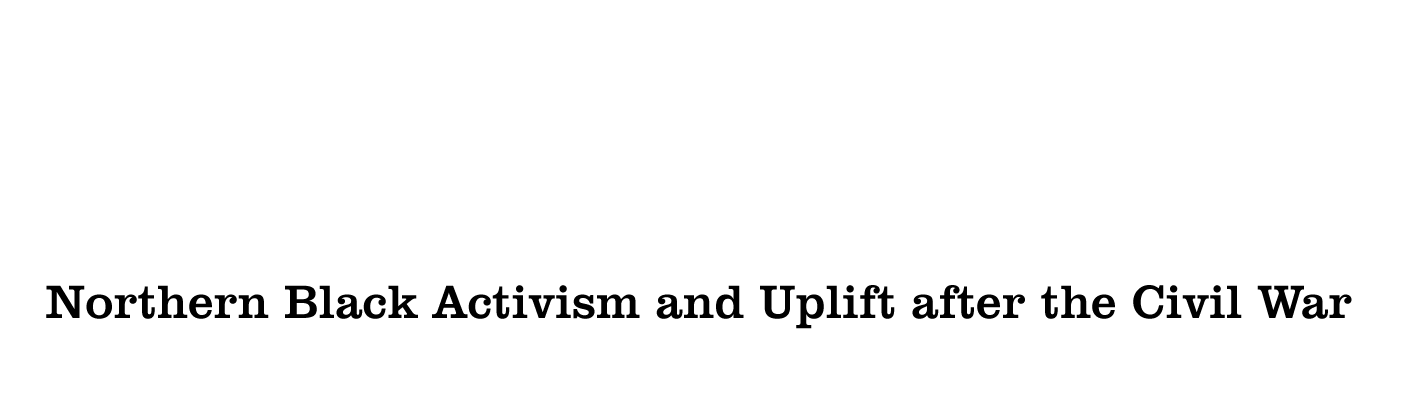

The Colored Volunteer: Marching into Dixie. New York: Currier & Ives, 1863.

During the Civil War, publishing firms such as Currier and Ives responded to the patriotic fervor in the North by producing lithographs which celebrated black soldiers’ military contributions in preserving the Union. Such inclusion was abandoned in the decades after the war as African Americans were notably absent from books about Civil War history.

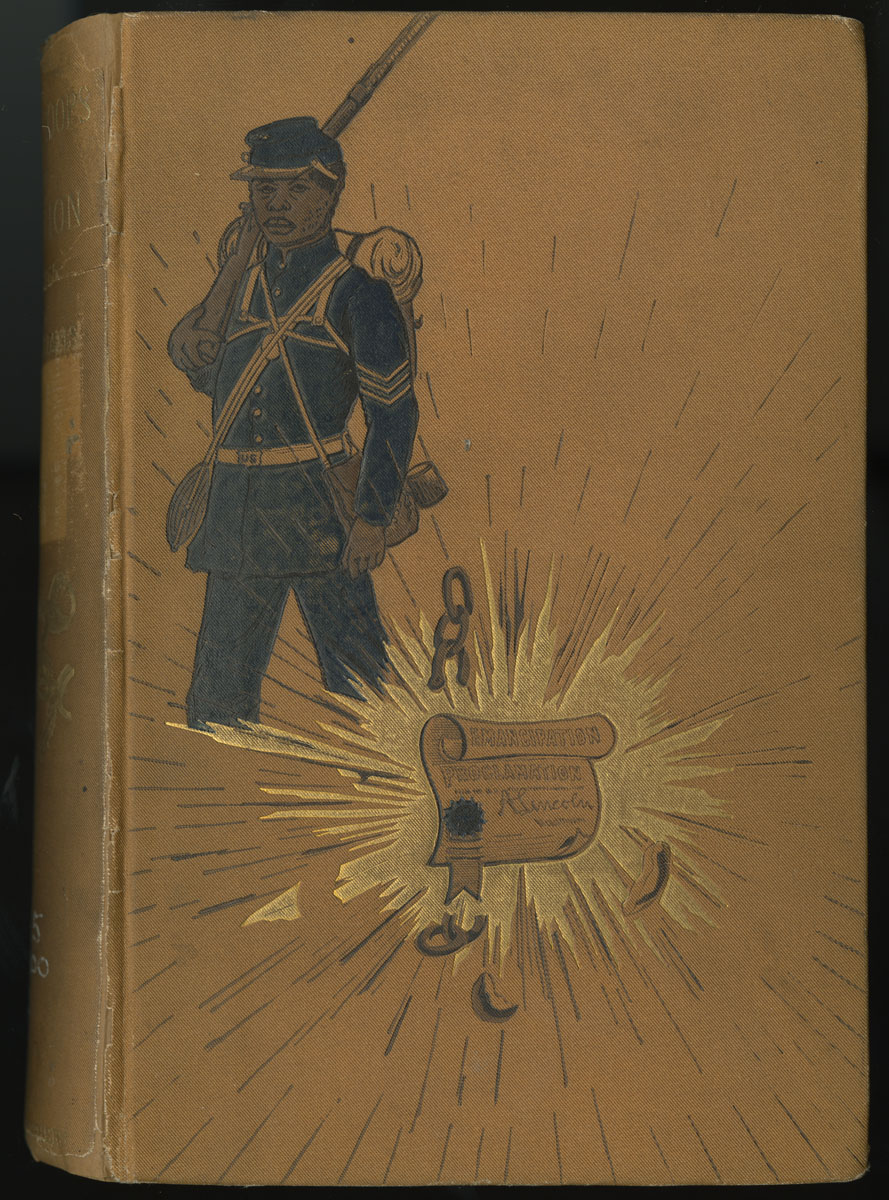

William Wells Brown. The Negro in the American Rebellion: His Heroism and His Fidelity. Boston: Lee & Shepard, 1867.

William Wells Brown’s The Negro in the American Rebellion was one of the first works by a black author to situate African Americans within the broad sweep of American history. Although the majority of the work is devoted to the Civil War, the first sections describe slave uprisings and early black military service in American wars. Primary sources such as newspaper accounts and government documents were reproduced at length in the work, providing evidence of African American heroism. For much of the interpretive narrative, Brown supplied no named sources or citations, a historiographical practice that was not unusual for the era. Published amidst Reconstruction debates, Brown argued that their wartime patriotism and valor warranted granting black Americans full citizenship rights, including black male suffrage.

George Washington Williams. A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1888.

A generation after the end of the Civil War, George Washington Williams (1849-1891) discovered that African Americans were largely absent from the growing body of histories of the conflict, spurring him to research and write this book. Williams was himself a veteran of the war, having enlisted in Pennsylvania under an assumed name and age when he was fourteen years old. Nevertheless, Williams decided against writing a history solely on his recollections, basing his analysis instead on archival research and interviews with veterans.

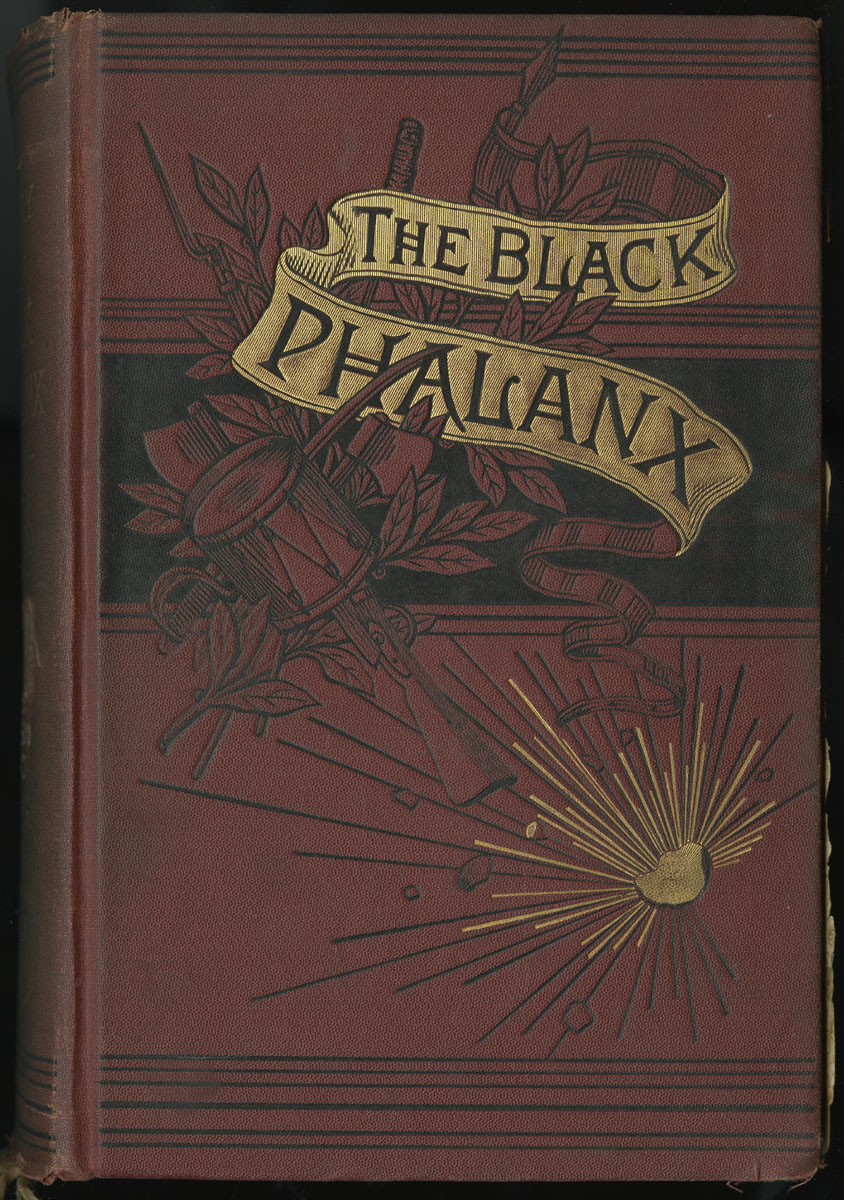

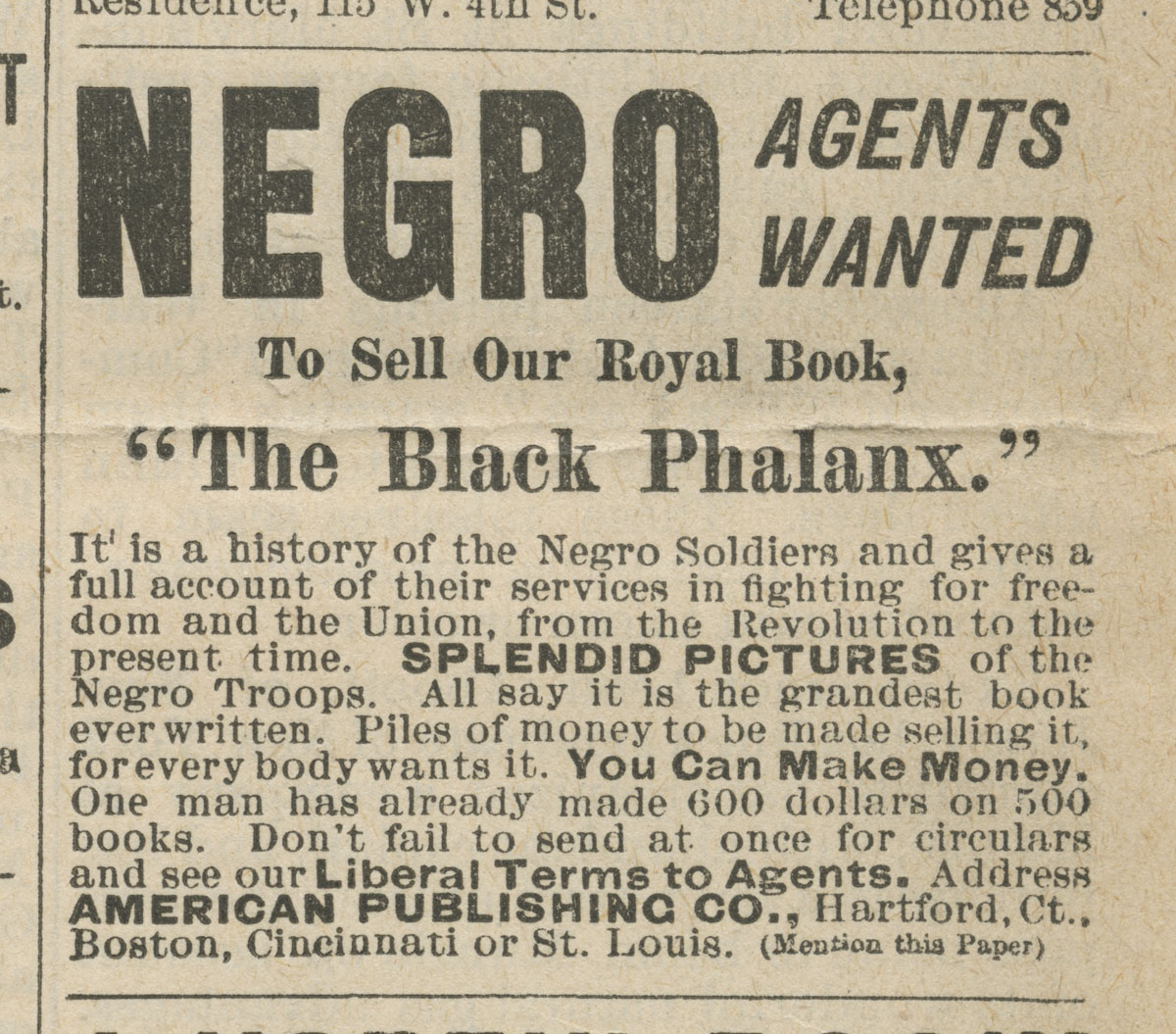

Joseph T. Wilson. The Black Phalanx: A History of the Negro Soldiers of the United States in the Wars of 1775-1812, 1861-’65. Hartford: American Publishing Company, 1888.

“The Black Phalanx.” The Freeman: The National Colored Weekly Newspaper (February 16, 1889).

Born in Virginia, Joseph T. Wilson (1836-1891) grew up in New Bedford, Massachusetts. In 1882, as a veteran of the Civil War and already a successful author of race literature, his local chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic encouraged him to write a history of African American soldiers. Similar to George Washington Williams, Wilson was a self-taught historian who embraced the use of archival records. Wilson “exhumed the bones of that noble Phalanx” of black soldiers by conducting research in the public libraries of Boston, Cincinnati, New Bedford, and New York, as well as by consulting private papers and the records of the U.S. War Department. Sold by subscription, The Black Phalanx was a popular work. By 1900, seven editions had been published.

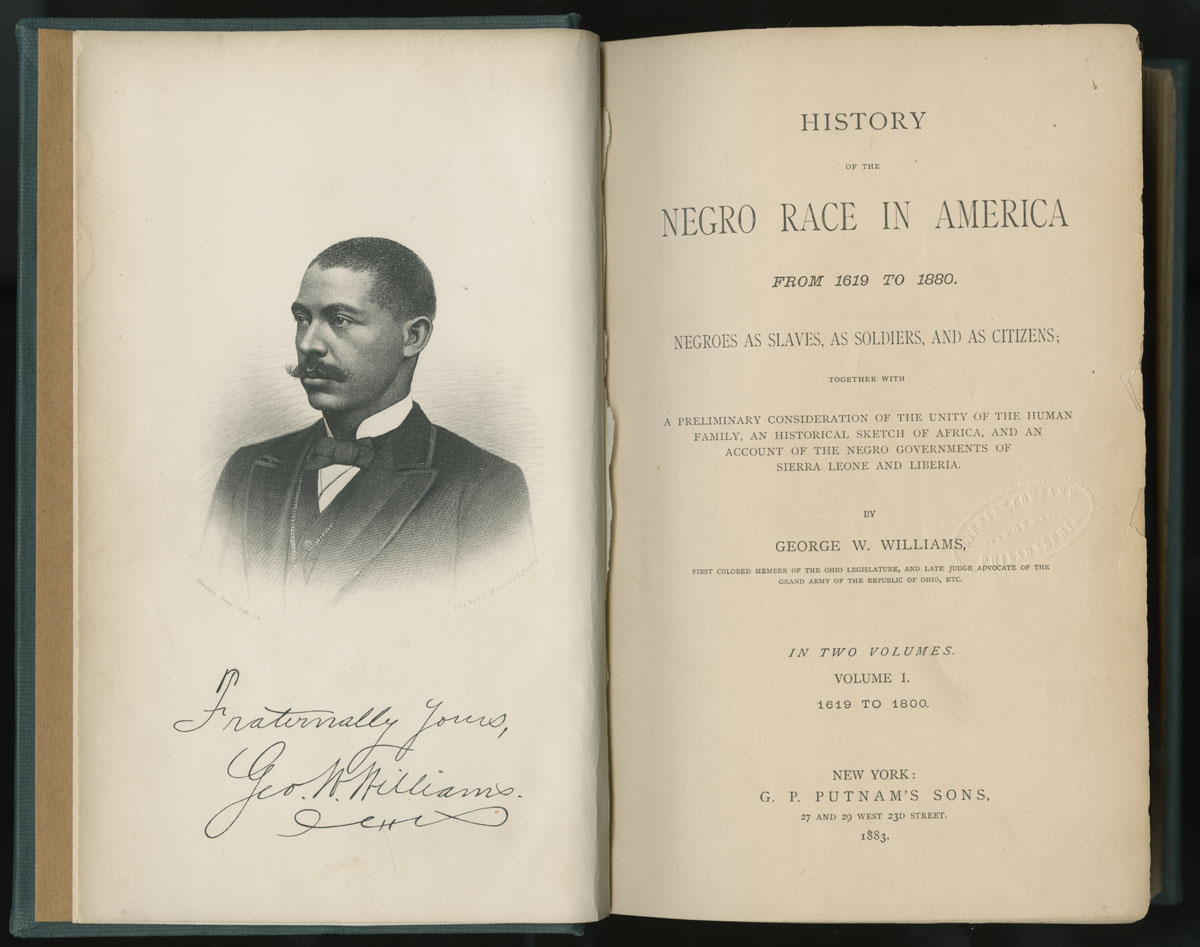

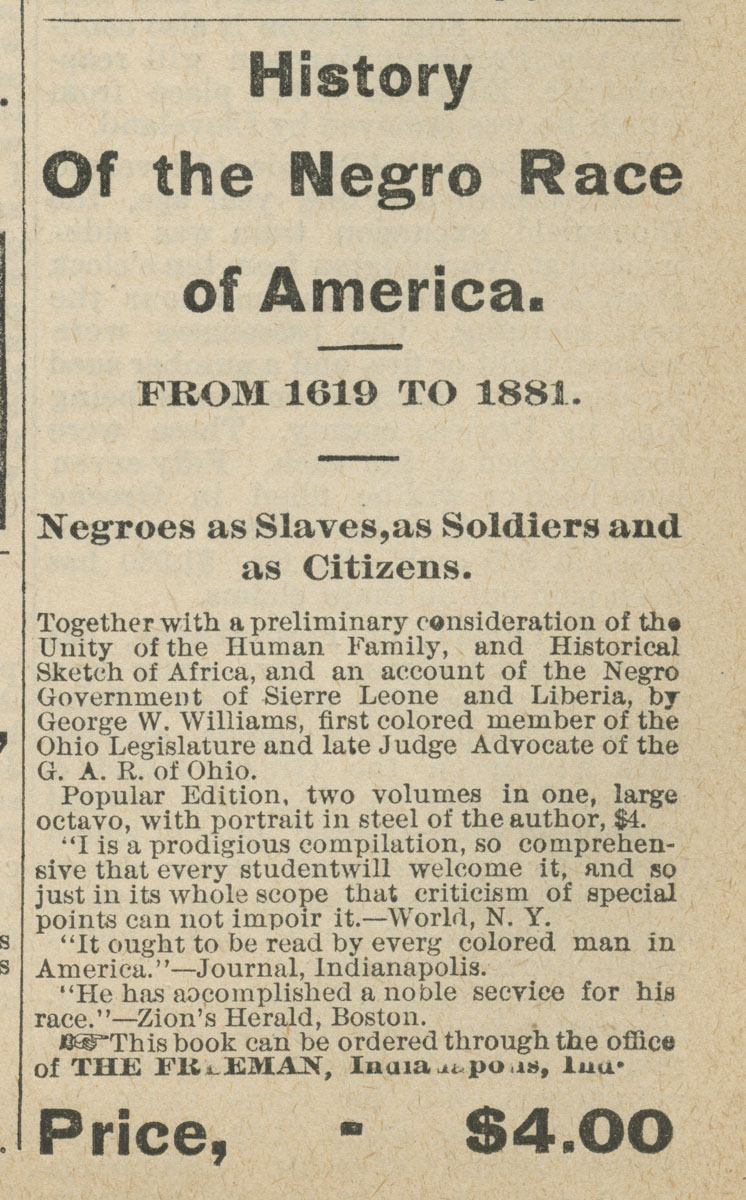

George Washington Williams. History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1883.

George Washington Williams served a term in the Ohio state legislature but chose not to continue in a political career so that he could devote his time to researching and writing. Although not trained as a historian, Williams employed a number of newly embraced historical methodologies, including the analysis of archival materials and the documentation of sources through citations and footnotes. The Massachusetts Historical Society and the Library of Congress were among the many archives in which he conducted research. To find sources that were absent from traditional archives, Williams placed advertisements in newspapers around the country, soliciting materials such as the minutes of black churches and statistics on black schools.

“A History of the Negro Race in America.” The Freeman: The National Colored Weekly Newspaper (February 16, 1889).

George Washington Williams’s A History of the Negro Race in America was widely reviewed by both the white and black press. He received overwhelmingly positive reviews from most sources, and black luminaries such as Booker T. Washington and Frederick Douglass recommended his History as essential reading for black Americans. One of the lone exceptions was William Calvin Chase, the editor of the black newspaper The Washington Bee, who seemed to have a personal vendetta against Williams and delighted in printing negative reviews week after week.

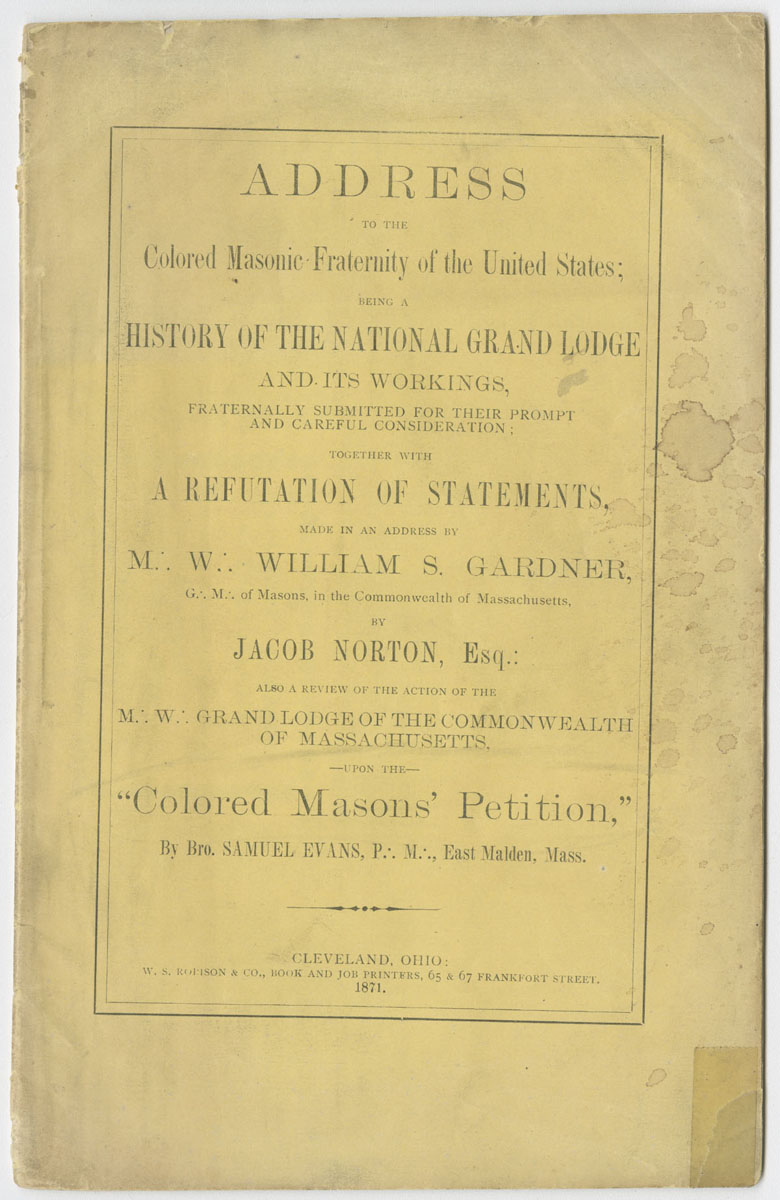

Address to the Colored Masonic Fraternity of the United States: Being a History of the National Grand Lodge and Its Workings. Cleveland: Robinson & Co., 1871.

William S. Gardner, a white mason from Massachusetts, wrote a history of American lodges, describing African American lodges as “illegal,” or unrecognized by the parent body, the National Grand Lodge. According to Gardner, African Americans made improper use of the masonic affiliation to solicit money. Peter H. Clark and other members of the Colored Masonic Fraternity compiled this history of black masonry in response, noting that they could not “afford to be idle or indifferent spectators” to this fiction about black masonry. Citing historical records tracing back to the establishment of black masonry by Prince Hall of Boston in 1784, the Colored Masonic Fraternity insisted on their legitimacy.

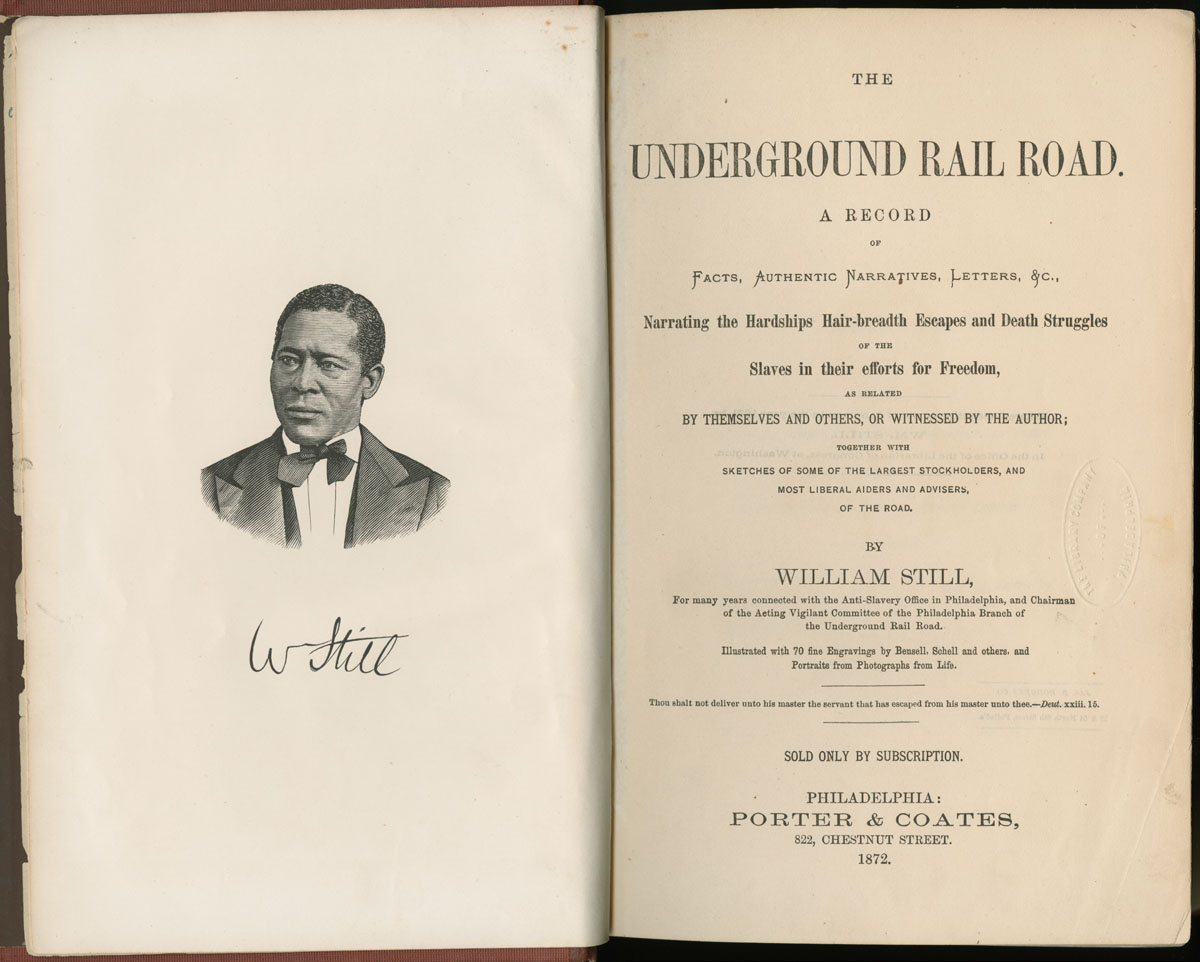

William Still. The Underground Rail Road. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872.

William Still (1821-1902) based The Underground Rail Road on the financial accounts and records from his tenure as Chair of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society’s Vigilance Committee, which assisted runaway slaves passing through Philadelphia. Although it was dangerous to keep records of what was then a federal crime, Still believed that the risks were outweighed by the benefits of potentially reuniting black families separated by slavery, of recording the bravery of freedom-seekers, and of documenting the cruelty of slavery.

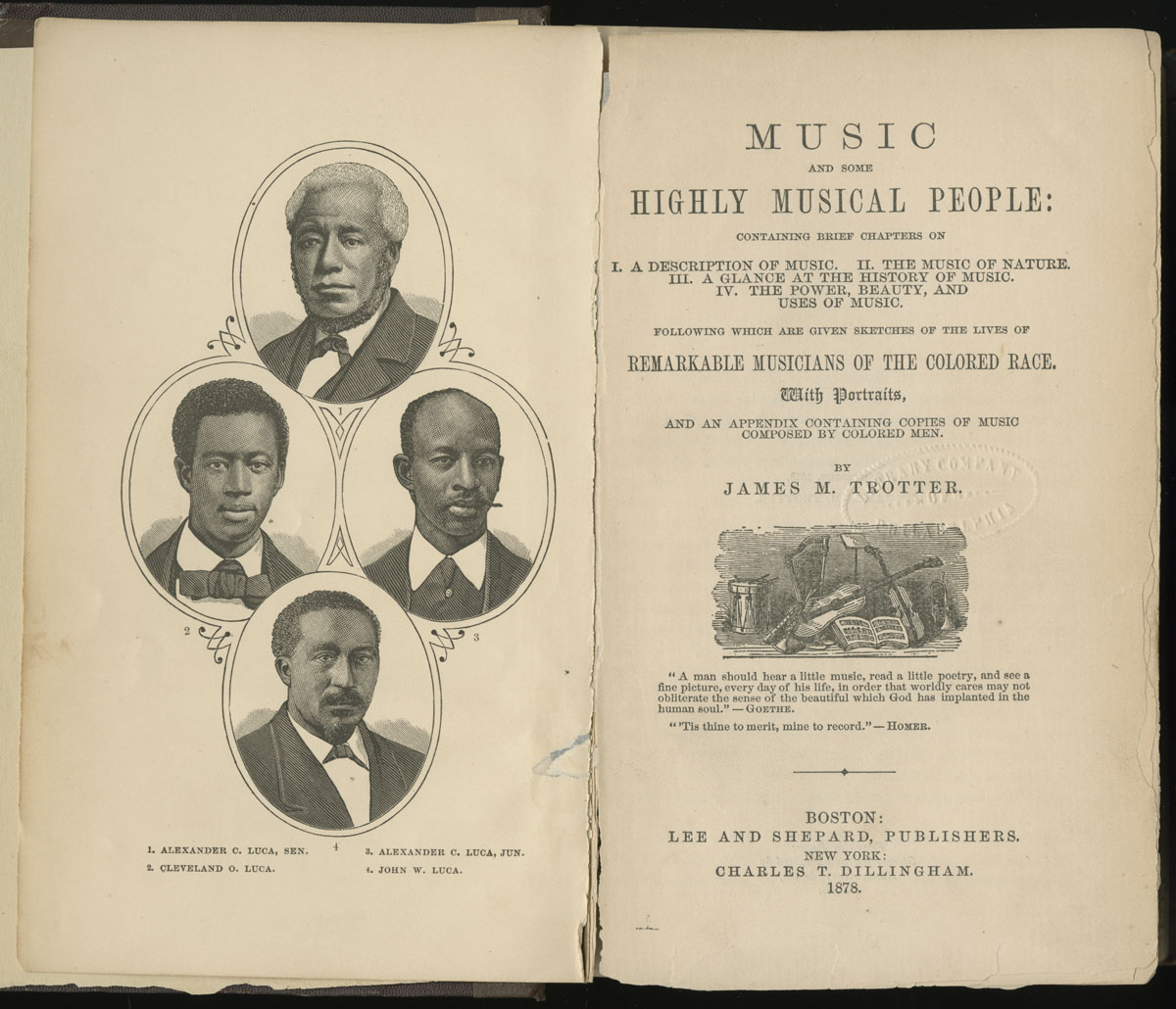

James M. Trotter. Music and Some Highly Musical People. Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1878.

In an age of Jim Crow minstrel shows, James Monroe Trotter (1842-1892) wrote this survey to counteract the “haze of complexional prejudice,” which dismissed the accomplishments of black musicians. Beginning with a description of music in the ancient world, Trotter described black musicians as talented performers of classical Western music as well as innovators. Trotter’s book featured sketches of dozens of African American musicians and musical genres including band leader Frank Johnson, concert singer Elizabeth Greenfield, enslaved pianist and composer “Blind Tom,” the Jubilee Singers, and the legacy of “slave-songs” or spirituals. Trotter conducted his research using a variety of sources, including scrapbooks, newspaper articles, and books.

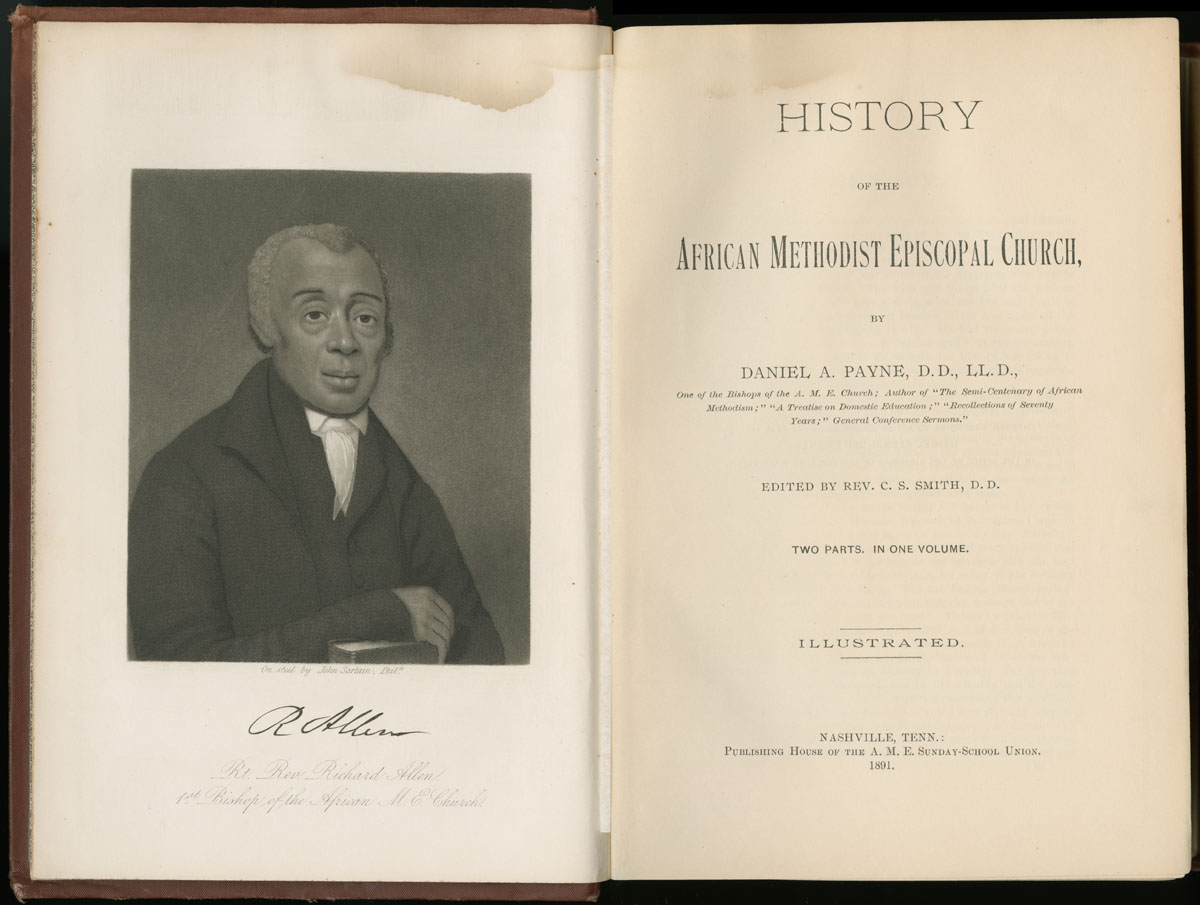

Daniel Alexander Payne. History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Nashville: Publishing House of the AME Sunday School Union, 1891.

Daniel Alexander Payne (1811-1893) was one of the AME Church’s most influential bishops during the 19th century. Although he was appointed the church historiographer in 1848, his duties delayed the writing and publication of this history until 1891. Deliberate in his research methods, Payne sought out conference proceedings and annual reports, interviewed church elders, and unearthed official records, including a trunk of documents that had belonged to Richard Allen. In his preface, Payne discusses historiographical methods and the need to maintain reliable records. He urges church secretaries and elders to keep comprehensive records and personal journals so that an accurate history will be preserved for the future.

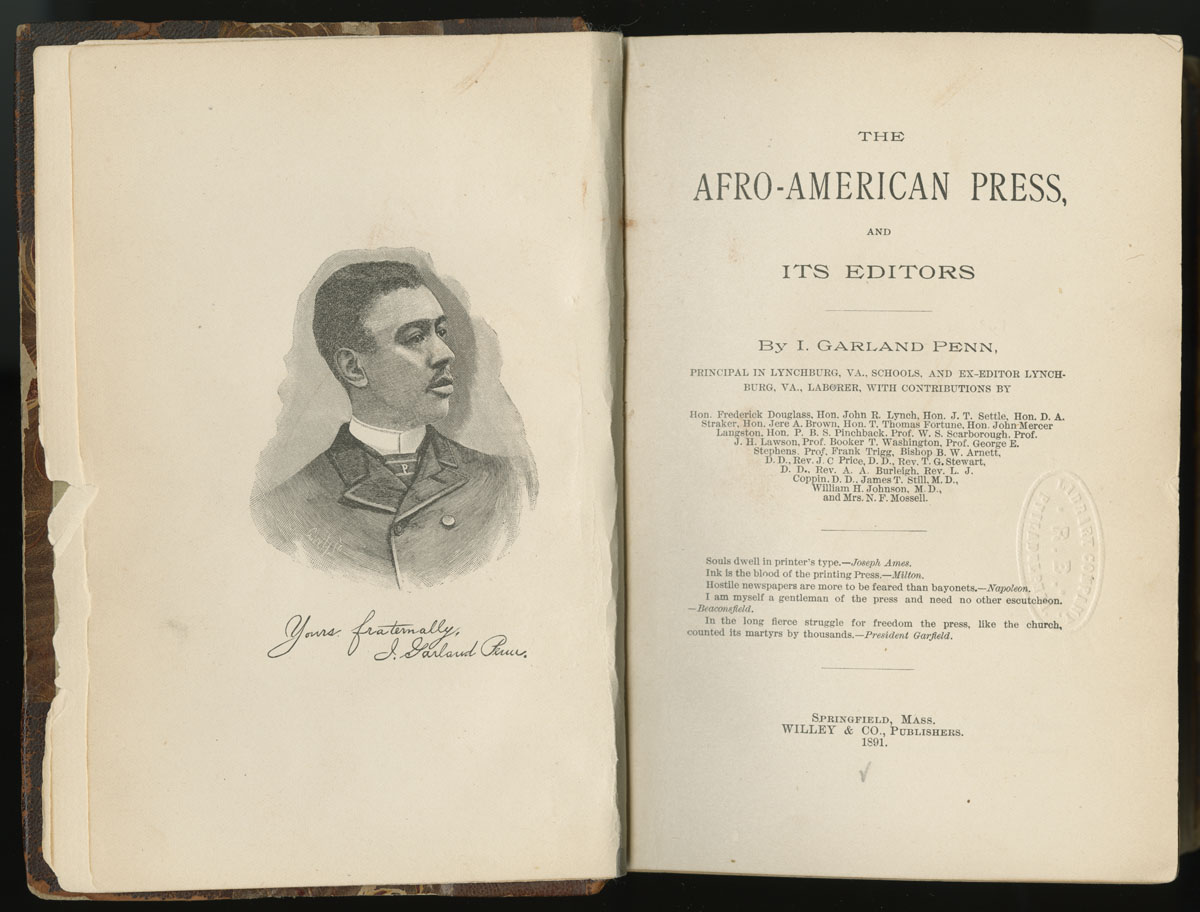

I. Garland Penn. The Afro-American Press and Its Editors. Springfield, MA: Willey & Co., 1891.

Part history, part encyclopedia, The Afro-American Press took a retrospective look at the black press in addition to documenting its current figures. Unlike many of the era’s historians, Irvine Garland Penn (1867-1930) gave women journalists and writers their due. Penn also recorded the activism of organizations such as the Afro-American League, which used newspapers to recruit members and disseminate information about its goals.

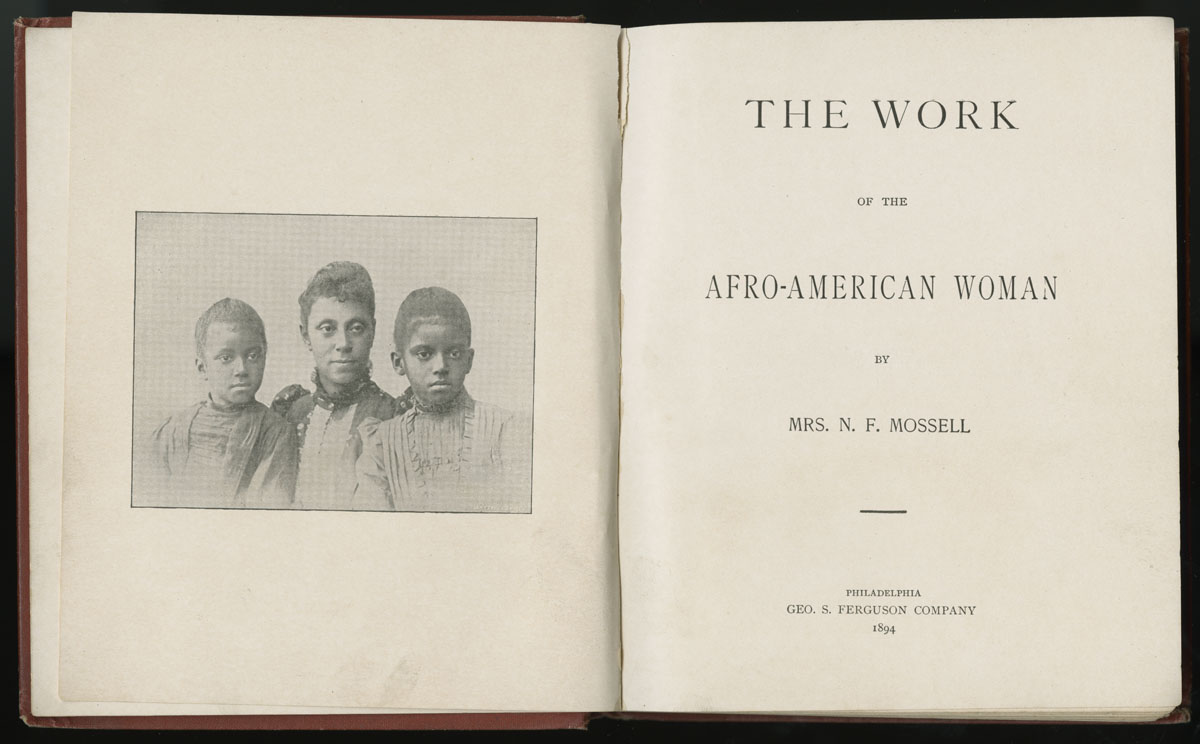

Mrs. N. F. Mossell. The Work of the Afro-American Woman. Philadelphia: Geo. S. Ferguson Company, 1894.

The Work of the Afro-American Woman was the rare work that examined black women’s contributions to African American history. The wife of prominent Philadelphia physician Dr. Nathan Mossell, Gertrude Bustill Mossell (1855-1948) had pursued a career in journalism prior to her marriage. Proud of marriage and of motherhood, as attested to by the use of her husband’s name and the frontispiece picturing her with her daughters, Mossell nevertheless believed that women could successfully continue their careers after marriage. Her book records the achievements of African American women doctors, nurses, teachers, and artists but focuses particularly on women in literary and journalistic fields.

The Success of the Season–Mrs. N. F. Mossell’s Book. Philadelphia, 1895.

The Work of the Afro-American Woman was praised in both the white and black press. It went into multiple printings, further attesting to its popularity. Mossell sold the book by subscription, using travelling agents who worked on commission to sell copies, a not uncommon method of the era.

John Stephens Durham. To Teach the Negro History: A Suggestion. Philadelphia: David McKay, 1897.

A graduate of the Institute for Colored Youth and the University of Pennsylvania, John Stephens Durham (1861-1919) had a varied career, which included serving as editor of Philadelphia’s Evening Bulletin and U.S. ambassador to Haiti, as well as practicing as an attorney in Philadelphia. To Teach the Negro History is a condensed version of a series of talks that he gave to students at Hampton Institute and Tuskegee Institute. Though he detailed the history of African Americans from the beginnings of enslavement to the present, he also urged his readers to ignore centuries of racial prejudice and to focus on self-improvement as a method of winning the sympathy of whites.

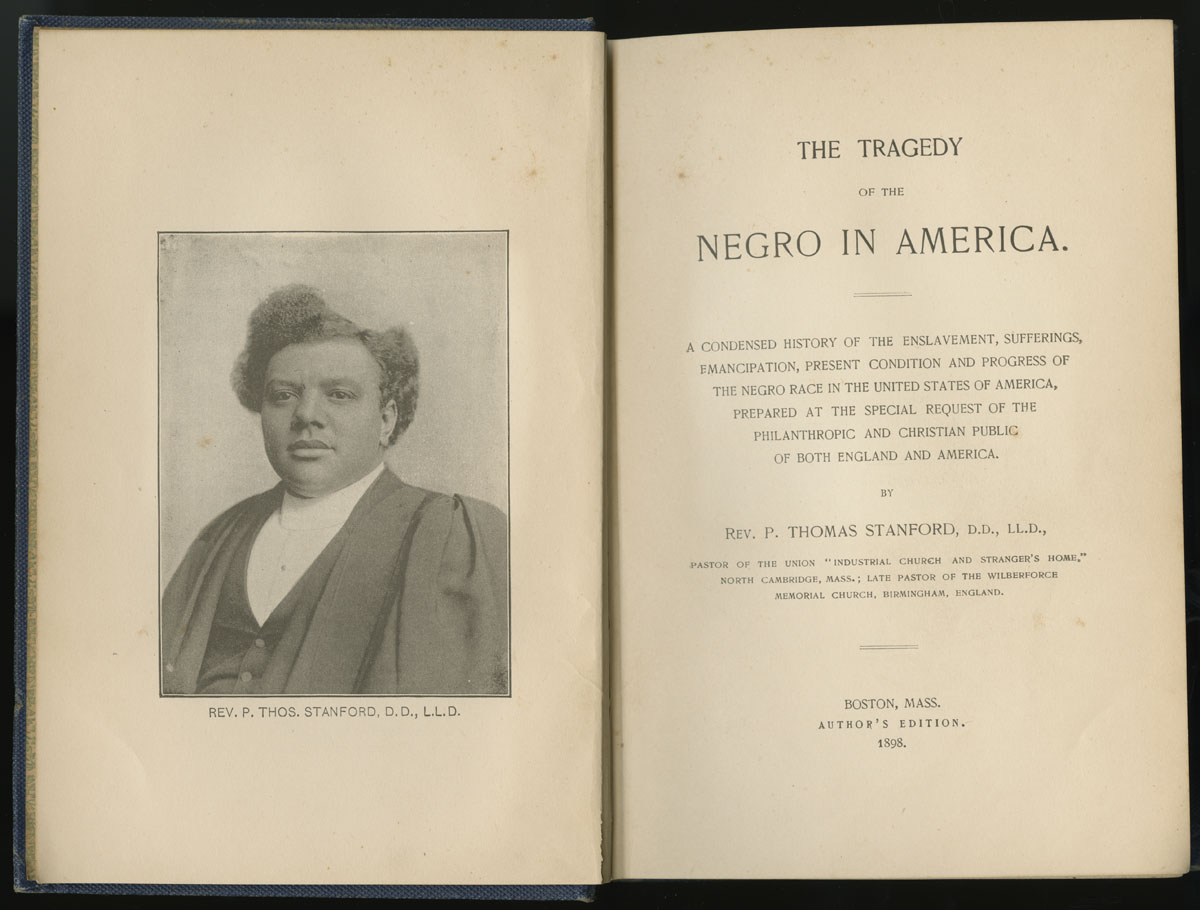

P. Thomas Stanford. Tragedy of the Negro in America: A Condensed History of the Enslavement, Sufferings, Emancipation, Present Condition and Progress of the Negro Race in the United States of America. Boston, 1898.

Peter Thomas Stanford (1858-1909) was born enslaved in Virginia but was adopted by a white Boston family after his parents died. He became an ordained minister, leading congregations in London, Ontario; Birmingham, England; and Haverhill, Massachusetts. Horrified by Southern lynching and the convict-leasing system, Stanford wrote this history in order to galvanize Christian activism by showing that “the outrages of to-day are merely repetitions of previous outrages.” Although Stanford consulted a number of histories and other firsthand accounts, his book uses this documentary evidence in the service of a religious condemnation of slavery and the Christians who helped perpetuate the institution.