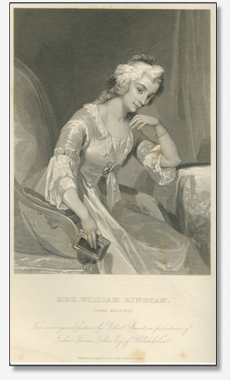

Rufus W. Griswold, The Republican Court, or, American Society in the Days of Washington. New and rev. ed. (New York, 1856), plate opposite 253. First ed., 1855.

ANNE WILLING BINGHAM (1764-1801) As one of Thomas Willing and Anne McCall’s ten children, and their eldest daughter, Anne Willing benefited from her family’s prominence in Philadelphia. With instruction from her mother, “Anne studied literature, writing, French, music, drawing, and embroidery.” At the same time, “her childhood and youth were filled with social engagements shared with children of elite families.”[1] In 1780, at age sixteen, she married William Bingham (1752-1804), one of the wealthiest of her many suitors, and, combining the Willing family prestige with her husband’s fortune, increased her ties to the Republican Court. From May 1783 to March 1786, the Binghams toured Europe and frequented many French and English courts. France’s aristocratic women, who often engaged in political dialogues in their social salons, seem to have made a strong impression on the young Mrs. Bingham. In a letter to Thomas Jefferson, a regular correspondent and friend, she describes the influence these Parisian women had, praising their ability to “interfere in the politics of the Country, and often give a decided turn to the fate of the empires.”[2] Moving throughout the social circles both in Paris and in London (where she would be presented at Queen Charlotte’s court in 1786),[3] Anne became well known for her intellect, elegance, and beauty.[4] While in London, the Binghams met regularly with John Adams and his family, who were also abroad at the time. In one letter, Mrs. Adams praises Anne:

Upon returning to America, Anne Bingham attempted to introduce a European-style court society in Philadelphia by hosting regular social gatherings.[6] Accordingly, the Binghams built one of the largest and most elegant homes in the country, Mansion House, which was fashioned after the London residence of the third Duke of Manchester. Located at the corner of Third and Spruce streets, this residence quickly became the heart of Philadelphia’s social gatherings as Anne Bingham gathered together fashionable Philadelphians and members of the new government. The Binghams’ parties had the reputation for their unprecedented extravagance[7] and in a short period of time Anne Bingham became known throughout the States as “unquestionably at the head of American society.”[8] Perhaps to emulate the Parisian salons, she often invited members of the Federalist Party to meet at the Mansion House, which became an informal center of discussion and debate for men such as George Washington, John Jay, and Alexander Hamilton. Thanks to her efforts, members of Philadelphia society mingled on a regular basis, which gave Mrs. Bingham the opportunity to display her worldliness, style, and intellect. The renowned artist Gilbert Stuart painted her at least twice; these portraits both depict her posing thoughtfully with her index finger marking a place in a book, indicating that she probably valued her education highly.[9] In 1800, after the birth of her third child, Anne contracted a serious illness, which was likely tuberculosis. Accompanied by her husband, her daughter, and her sister, she set sail for Madeira in search of a more favorable climate, but died in Bermuda on May 11, 1801, at the age of thirty-seven.[10] Her untimely death stole from Philadelphia one of its most admired citizens and contributed to the decline of the Republican Court’s reign over American society. Written by Annie Turner. ______________________ [1] American National Biography, s.v. “Bingham, Anne Willing.” [2] Notable American Women 1607-1950, s.v. “Bingham, Anne Willing.” [3] Carrie Rebora Barratt and Ellen G. Miles, Gilbert Stuart (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004), 195. [4] Rufus W. Griswold, The Republican Court, or, American Society in the Days of Washington (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1867), 296-302. [5] Ibid., 296. [6] Ibid., 297. [7] Anne Bingham’s cousin, Joshua Francis Fisher, said of his Philadelphia relatives: “certainly there never was in our country a series of such distinguished réunions. Brilliant balls, sumptuous dinners and constant receptions.” (Quoted in Barratt and Miles, Gilbert Stuart, 195.) [8] Griswold, The Republican Court, 301. [9] An engraving after one of the portraits is pictured here; the other can be found in Barratt and Miles, Gilbert Stuart, 197. [10] Ibid., 198. |