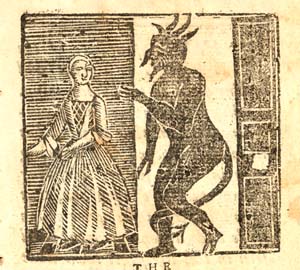

The principal character in much early American popular literature was the Devil, whether he appeared in the guise of the villain in a ballad or a tale, the seducer in a novel, the barbarous Other in a captivity narrative, the criminal, or the enemy. Even when the angels won in the end, the Devil provided the interest and drama. Quite often, though, in early American popular writing, the Devil appeared in person, and he was frequently illustrated, complete with horns, a barbed tail, and (in racist America at least) black skin. These woodcuts were fascinating even to those who could not read the text.

Cotton Mather. The Wonders of the Invisible World. Observations … upon the Nature, the Number, and the Operations of the DEVILS. Boston: B. Harris, 1693.

Cotton Mather’s account of the Salem witch trials was the first publication of the testimony in the infamous episode that added the phrase “witch-hunt” to our language. Mather was not a participant in the proceedings, and he claimed only to report them objectively, though his ulterior motive was to clear his clergymen friends of charges of judicial misconduct. Just what was going on in Salem in 1692 is still debated, but Mather’s reporting of the proceedings has preserved a great deal of information about the lives and religious practices of ordinary people of early New England.

Elisha Rich. The number of the beast found out by spiritual arithmetic. … By which is plainly discover’, some of the secret depths of Satan. Chelmsford: N. Coverly, 1775.

Rich was the minister in Chelmsford, where his sensational treatise on the nature of the Devil was published. He cites scriptural proof of the number that marks the Devil— 666— and provides bizarre type-metal illustrations showing Beelzebub ravaging the earth.

The Prodigal daughter, or A strange and wonderful relation, shewing how a gentleman of a vast estate in Bristol, had a proud and disobedient daughter, who because her parents would not support her in all extravagance, bargained with the Devil to poison them.Worcester: [Isaiah Thomas], 1787.

The prodigal daughter dressed up in revealing clothes (ineptly displayed on the title page) and stayed out all night. When “Her father he did ask her where she’ been? / She straightway answer’ what was that to him?” After that it was but a short step to striking a bargain with the Devil (here portrayed as a gentleman) to poison her parents. In the end she repents of her sin and is forgiven by God and her parents.

Nathan Culver. A very remarkable account of the vision of Nathan Culver … Shewing how he was converted to the truth, by an extraordinary and immediate revelation, Jan. 10, 1791. Boston: Printed by E. Russell, near Liberty-Pole. 1795. (With privilege of copy-right.) (Price 3s. per dozen, and six pence single.) Where is now for sale, Mary and Martha’s dialogue, and several other serious pamphlets.

Nathan Culver doubted the existence of heaven and hell, until one night he had a dream in which Christ gave him a tour of heaven and a horrifying glimpse of the Devil tormenting souls; and so his life was changed. In early America many books of prophecy were published, and many sermons in which God’s plan was revealed, almost all written by ordained clergymen. Nathan Culver was an obscure man whose personal revelation was reprinted at least six times. It was so popular that the publisher of this edition even went to the trouble of claiming a copyright on it. The imprint indicates that it was sold to peddlers cheaper by the dozen, along with Mary and Martha’s Dialogue, another religious pamphlet by an obscure layperson, a copy of which is in the On the Margins section.

The Indian’s Pedigree. [Boston]: Printed for the Purchaser [by E. Russell], 1794.

This blatantly racist doggerel poem argues that Indians are “one half hog, the other Devil.” The woodcut of the Devil at the upper right was also used on an inside page of The Devil; or, the New-Jersey Dance (also displayed here), published by Ezekiel Russell, near the Liberty Pole in Boston. Many of his imprints are in this exhibition. Printers like Russell who supplied country peddlers were often located at the edge of town, so their clients did not need to venture too far into the urban maze. The Liberty Pole, on the site of the Liberty Tree cut down by the British in 1775, was on the main road into Boston from the south, just where the first city streets began to cross it. see image below

The Devil. Or, the New-Jersey Dance. A horrid relation of facts which took place a few weeks ago … Published at the request of many people. Boston: Printed and sold at Russell’s, near Liberty-Pole, 1797.

This attack on dancing and other licentious behavior is cast as a news report about a satanic visitation. Three young couples in New Jersey decided to spend the evening dancing, and they hired a fiddler to provide the music. When the musician left after a few hours, the intoxicated dancers were so frustrated that one of them swore he “would have a Fidler, if he went to hell for him and danced to eternity!” Immediately, another fiddler appeared “who seemed to be a black man.” He began to play, and the dancing “has continued without intermission, for more than thirty days.” Strangely, no one was able to break down the doors of the house, but eyewitnesses reported seeing the couples through a keyhole “dancing on the stumps of their legs to infer-nal music, their feet being worn off, and the floor streaming with blood.” see image below

The Wonderful appearance of an angel, devil & ghost, to a gentleman in the town of Boston.Boston: J. Boyle, 1774.

A Tory gentleman is convinced of the error of his ways by supernatural visitations. The Devil is particularly persuasive, arguing that opposition to the patriot cause amounts to treason, for which he will be condemned to hell. In the woodcut (which may be by Paul Revere) the Devil carries a folio book and a halter, the two main tools he uses to lure people to perdition. The Devil is not only the subject of much popular literature, he is also its purveyor.

Jacob Green. A vision of hell, and a discovery of some of the consultations and devices there, in the year 1767. By Theodorus Van Shemain. Boston: J. Boyle, 1773 [and] West-Springfield: E. Gray, 1798.

The narrator has a vision of a sort of cabinet meeting of chief devils in which ways to deceive the people are debated. They decide to wage a campaign of disinformation, spreading the word that ministers are too worldly, that Sunday is a good day to visit friends and have a good time, etc. The woodcuts are by Paul Revere. see image below