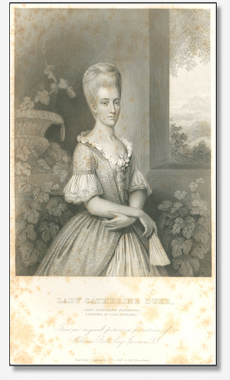

Rufus W. Griswold, The Republican Court, or, American Society in the Days of Washington. New and rev. ed. (New York, 1856), plate opposite 27. First ed., 1855.

CATHERINE ALEXANDER DUER (1755-1826) Catherine Alexander was born to William Alexander, known as Lord Stirling, and Sarah Livingston of New York. As a Livingston, her mother was a member of the prominent Hudson Valley family, and a sister of Philip Livingston, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Alexander, a major general in the American Revolution, was a self-proclaimed Scottish earl (although his title was never recognized officially), and for this reason Catherine gained the nickname “Lady Kitty.”[1] Lady Kitty grew up in the company of celebrated generals, revolutionaries, and their families. On several occasions, George Washington himself visited the Alexander home in Basking Ridge, New Jersey, and gave Lady Kitty away at her 1779 wedding to Colonel William Duer (1747-1799).[2] Her new husband, with whom Kitty would have seven children, became a leading businessman and stockbroker, and his wealth made it possible for his wife to host extravagant parties. The Rev. Manasseh Cutler, after attending a dinner party in 1787 at the Duer household in New York City, observed:

Directly related to Sarah Livingston Jay (the two women were first cousins), and more distantly to Alexander Hamilton, Lady Kitty and Colonel Duer were on the guest lists for New York City’s most prestigious social gatherings, including George Washington’s first Inauguration Ball.[4] She also helped outfit one of New York City’s finest mansions for use by the president and his famiy. In a letter dated April 30, 1789, Sally Franklin Robinson writes:

In addition to her roles as hostess, socialite, and even interior decorator, Kitty Duer also participated in family financial matters. Surviving correspondence indicates that she occasionally handled bank transactions for her husband: in one letter she notes borrowing 1,100 dollars on Duer’s behalf, and also explains that she will have to pay for some expenses while he is away.[6] Duer (who had, while secretary of the Board of Treasury during the Revolution, helped Robert Morris finance the war) borrowed extensively on credit that he could not repay, and when the stock market bubble burst in the spring of 1792, he was left with a debt of about $3,000,000—more than $40,000,000 today.[7] Arrested and thrown into debtors’ prison that March, where he would die in 1799, Duer left Lady Kitty with virtually nothing. His actions as a speculator set off the Panic of 1792, the first real economic crash for the new nation. With her life of luxury ended, Lady Kitty and her eight children moved from their grand home on Broadway to a small brick house on Chambers Street, where she took in boarders. With her subsequent marriage to merchant William Neilson, several more children joined the household. Despite her straitened circumstances, Lady Kitty did not fall out of contact with members of the Republican Court. [8] Written by Annie Turner. ______________________ [1] Edith Tunis Sale, Old Time Belles and Cavaliers (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1912), 152. [2] Charles R. Geisst, Wall Street: A History, From Its Beginnings to the Fall of Enron (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 12. [3] Robert Francis Jones, The King of the Alley: William Duer, Politician, Entrepreneur, and Speculator, 1768-1799 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1992), 96. [4] Rufus W. Griswold, The Republican Court, or, American Society in the Days of Washington (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1867), 156. [5] Sally Robinson to Kitty Wistar, April 30, 1789, quoted in Anne H. Wharton, “Washington’s New York Residence in 1789,” Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine 43 (May 1889):742. [6] Catherine Duer to William Duer, undated, quoted in Robert E. Wright, “Women and Finance in the Early National U.S.” in Essays in History (Charlottesville: The University of Virginia, 2000), vol. 42, http://etext.virginia.edu/journals/EH/EH42/Wright42.html (accessed June 30, 2008). [7] Bruce H. Mann, Republic of Debtors: Bankruptcy in the Age of American Independence (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2002), 114. [8] Eric Homberger, Mrs. Astor’s New York: Money and Power in a Gilded Age (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 48-52.

|