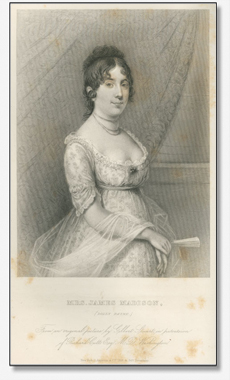

Rufus W. Griswold, The Republican Court, or, American Society in the Days of Washington. New and rev. ed. (New York, 1856), plate opposite 69. First ed., 1855.

DOLLEY PAYNE TODD MADISON (1768-1849) Dolley Payne was born in a Quaker community in rural North Carolina, the oldest daughter of John and Mary Coles Payne. There, John Payne was a planter and slave owner, but in 1783, he freed his slaves and moved his family to Philadelphia. It was in that city that Dolley was introduced to elite families, befriending Sally McKean, the daughter of the governor of Pennsylvania, and other well-to-do citizens. In 1790, Dolley Payne married lawyer and fellow Quaker John Todd Jr., and with him had two sons, John Payne and William Temple. However, in 1793, a yellow fever epidemic swept through Philadelphia, killing the infant William and his father, and leaving Dolley a widow with a young son to support.[1] Rufus Griswold writes, “becoming a widow she threw off drab silks and plain laces [typical of Quakers], and was for several years one of the gayest and most fascinating women of the city.”[2] One year after the deaths of her husband and son, Dolley’s friend, Senator Aaron Burr, introduced her to Congressman James Madison Jr. (1751-1836). Later that year, they married, but as a result of her marriage to Madison, a non-Quaker, Dolley was expelled from the sect.[3] Once shunned, she focused on her new role as the wife of a politician, and became one of the most famous women associated with the nation’s founding fathers. When Madison’s term ended, the family left Philadelphia for his family’s plantation in Montpelier, Virginia, where they remained until he was appointed secretary of state to President Thomas Jefferson in 1801.[4] The Madisons moved with Jefferson to Washington, D.C., the new capital city. There, Dolley became “official hostess” for President Jefferson, a widower,[5] when his daughter Patsy was not serving as such. Throughout Jefferson’s presidency, then into her own husband’s time as commander-in-chief, Dolley never failed to impress with her hosting abilities. While in Washington, D.C., Dolley held “soirees [which] allowed women more freedom than they had ever known in small New England towns or even cities like Philadelphia.”[6] A popular hostess with a mind for politics, Dolley dabbled in finery and high fashion, and even was known for taking snuff in her own parties, but she also attended congressional debates and Supreme Court deliberations. She invited politicians and their wives to mingle in her drawing room, where they tasted rich food and drink, listened to music, played cards, and talked with one another. Her remarkable affability made it possible for her to help her less charismatic husband achieve his political goals.[7] Dolley Madison is perhaps most famous today for saving a collection of government documents and a Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington when, in 1814, the British troops invaded Washington, D.C., and destroyed the White House. She died in 1849, thirteen years after her husband, and was survived by her son, John Payne. Written by Annie Turner. Other portraits appear in:

______________________ [1] Richard N. Cote, Strength and Honor: The Life of Dolley Madison (Mount Pleasant, South Carolina: Corinthian Books, 2004), vi. [2] Rufus W. Griswold, The Republican Court, or, American Society in the Days of Washington (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1867), 395. [3] Cote, Strength and Honor, vi. [4] “Becoming Americans: Dolley Madison,” in The Story of Virginia: The American Experience, The Virginia Historical Society, http://www.vahistorical.org/sva2003/dm.htm (accessed 15 August 2008). [5] Catherine Allgor, Parlor Politics: In Which the Ladies of Washington Help Build a City and a Government (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000), 31. [6] Ibid., 85. [7] Catherine Allgor, A Perfect Union: Dolley Madison and the Creation of the American Nation (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 2006). |