|

Receipt to Joseph Nye for the services of “his Negro boy named Jack” to the Continental Army. Sandwich, July 14, 1780. |

|

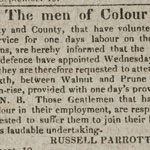

Announcement from Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser, September 27, 1814.

|

|

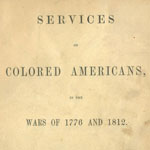

William Cooper Nell, Services of Colored Americans in the Wars of 1776 and 1812. Second edition (Boston, 1852). |

|

Letter of Cato and Petition by “the negroes who obtained freedom by the late act,” in Postscript to the Freeman’s Journal, September 21, 1781.

Pennsylvania slaveholders whose slaves were freed because they were not registered according to the provisions of the Gradual Emancipation Act urged the Pennsylvania Assembly to rescind the act for two years, effectively returning the freed slaves to bondage. In his brief letter accompanying an appeal by a group of blacks, Cato, “a poor negro,” urged the Assembly to uphold the act. “To make a law to hang us all would be merciful, when compared to this law, for many of our masters would treat us with unheard of barbarity for daring to take advantage (as we have done) of the law made in our favor.” There appeal was successful. |

|

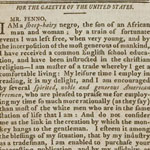

Exchange between “Rusticus” and “Africanus,” in Gazette of the United States, March 3, 1790.

Rusticus here argues against emancipation, raising fears of interracial sex leading to a generation of “great grand daughters [who] will have black muzzles and crooked figures.” Blacks, he argues are innately inferior and “when higher orders intermix with lower ones, the original character is gradually debased.”

Black respondent Africanus asserts the common humanity of all races. “The American and the African are but one species . . . And I, a sheep-hairy African negro, being free and in some degree enlightened, feel myself equal to the duties of [any] spirited, noble, and generous American freeman.” |

|

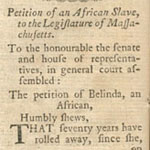

“Petition of an African Slave, to the Legislature of Massachusetts,” in The American Museum . . . for June, 1787.

In her affecting petition the aged former slave Belinda recounts her capture in Africa and her fifty years of servitude to Isaac Royal, a loyalist who fled to England. Belinda requests a portion of Royal’s seized estate, “a part of which has been accumulated by her own industry and the whole augmented by her servitude,” to sustain her in old age. Belinda’s petition was originally submitted in 1782, while the Revolutionary war still raged. |

|

“To the honourable the senate and house of representatives of the commonwealth of Massachusetts . . . the petition of a great number of blacks,” in The American Museum . . . for May, 1788.

Boston leader Prince Hall, founder of African American Freemasonry, authored this appeal protesting the kidnapping of three free black seamen, one instance of many. His appeal is also a brief against the slave trade, urging Connecticut to abolish it. In March of 1788, the Connecticut legislature did abolish the trade within the state. The three seamen were found in the French island of St. Bartholomew and returned to Boston. |

|

“To the President, Senate, and House of Representatives. The Petition of the People of Colour, free men, within the City and Suburbs of Philadelphia, humbly sheweth,” in John Parrish, Remarks on the Slavery of the Black People (Philadelphia, 1806). |

|

“Kidnapping,” stipple engraving by Alexander Rider in Jesse Torrey, Portraiture of Domestic Slavery (Philadelphia, 1817).

The practice of kidnapping free blacks to sell into slavery that Prince Hall protested in Boston was widespread in states close to slavery, like Pennsylvania, and Philadelphia’s growing black population made it a popular target for kidnappers. In this 1799 petition, Absalom Jones demands federal action against this interstate crime. “If the Bill of Rights or the Declaration of Congress are of any validity, we beseech that as we are men, we may be admitted to partake of the liberties and unalienable rights therein held forth.” Eighteen years after this petition abolitionist Jesse Torrey would write of the persistent kidnapping crisis in Philadelphia. |

|

To the Honorable the General Assembly of the State of Connecticut . . .The Memorial of Harry, Cuff, and Cato, Black Men, Now in Slavery in Connecticut, in Behalf of Ourselves and the Poor Black People of Our Nation in Like Circumstance (Hartford, 1797).

Connecticut’s Gradual Emancipation Act of 1784, like Pennsylvania’s, freed no one immediately. Connecticut slaveholders often shipped slaves south for sale rather than lose them to eventual emancipation. Finally, in 1788, the legislature passed a law forbidding the practice, but Harry, Cuff, and Cato complained it was unenforceable as the victims were scattered and difficult to find, and their testimony in court disregarded. |

![A[bsalom] J[ones] and R[ichard] A[llen], A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People during the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia in the Year 1793: And a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown upon Them in Some Late Publications (Philadelphia, 1794).](images/section6/th13-11.jpg) |

A[bsalom] J[ones] and R[ichard] A[llen], A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People during the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia in the Year 1793: And a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown upon Them in Some Late Publications (Philadelphia, 1794).

French refugees fleeing the slave revolution in Saint Domingue in the summer of 1793 brought not only themselves and many of their slaves but also the Aedes aegypti mosquito and the devastating yellow fever epidemic. In early September, as thousands were fleeing and hundreds were dying, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones mobilized free blacks to nurse the sick and bury the dead. Working the streets and visiting the homes, they were effectively an arm of the government of the stricken city.

In his popular account of the epidemic, Mathew Cary charged some blacks with extortion and theft. Though Cary was complementary to the two, Allen and Jones felt their community was insulted and shot back with their compelling account of the blacks’ efforts, while thousands of others (including Cary) fled the city in fear. Written with barely controlled anger, Allen and Jones authored the most detailed defense of a free black community yet to appear in print, including a resounding denunciation of the slavery-inspired racism that made many whites belittle and dismiss their actions. Allen and Jones gave this copy to the Library Company in 1794. |

|

Confession of John Joyce, Alias Davis, Who Was Executed on Monday, the 14th of March, 1808, for the Murder of Mrs. Sarah Cross; With an Address to the Public, and People of Colour (Philadelphia, 1808).

The black crime rate in the 1790s was very low, but grew in the next decade as the black population increased by over 4,000 people, many poor emigrants like the former Maryland slaves John Joyce and Peter Matthias, whose botched robbery of the home of Sarah Cross led to murder. Richard Allen published this account of the trial, confession, and execution of Joyce and Matthias for Philadelphia black readers with his sermon calling on blacks to reject sin for fear of their souls. “See the tendency of dishonesty and lust, of drunkenness and stealing, in the murder. While the lustful dance is delighting thee, forget not, that ‘for all these things God will bring thee into judgment.’” Allen, with Absalom Jones and others, formed a Committee for the Suppression of Vice to promote the moral behavior of the black community. |

|

Daniel Coker, A Dialogue between a Virginian and an African Minister Humbly Dedicated to the People of Colour in the United States of America (Baltimore, 1810). Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

This black Baltimore minister’s pamphlet is a unique contribution to American antislavery literature, a rational point-by-point dissection and refutation of proslavery arguments in the form of a dialogue with a white Virginian. Reasonable rather than revolutionary, Coker proposes a national gradual emancipation plan with slaves paid for labor to eventually purchase themselves. Coker challenges racist assumptions of black inferiority by introducing a cast of accomplished African Americans and, shown here, an account of the spread and progress of black churches. |

![[James Forten,] “Letters from a Man of Colour, On Late Bill Before the Senate of Pennsylvania,” in Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser, April 13, 1813.](images/section6/th13-14.jpg) |

[James Forten,] “Letters from a Man of Colour, On Late Bill Before the Senate of Pennsylvania,” in Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser, April 13, 1813.

Growing white resentment of the black community led to the introduction of a bill to restrict the immigration of any more blacks into the state, require registration of those here, impose a special tax, and require bondage of any convicted of a crime. Blacks and white abolitionists protested in a memorial to the legislature, and James Forten contributed his anonymous series of thoughtful letters serialized in the local press and later published as a pamphlet. He urged rejection of special laws for blacks as a crude throwback to slavery days, “let the motto of our Legislator be “The Law knows no distinction.’” The proposed legislation quickly died. |

|

David Walker, Walker’s Appeal, in Four Articles, Together with a Preamble to the Colored Citizens of the World, But in Particular, and Very Expressly to Those of the United States of America (Boston, 1829).

David Walker rejected the reasonable and polite temper of most black antislavery writers in favor of passionate fury at slavery, racism, white Christianity, and colonization. His audience was blacks not whites, a call to action, protest, and rebellion. Walker saw his pamphlet through three editions between this first of 1829 and the third of 1831, shortly before his death. Black seamen carried his pamphlet to slaves in the south, and its discovery by whites set off a firestorm of persecution. In several slave states antislavery literature was banned as incendiary and fomenting slave insurrection, a capital offense. Any slave found with Walker’s pamphlet faced hanging. |

|

Freedom’s Journal, March 30, 1827. Photo reproduction (Springfield, 1891).

Black writers were dependent upon sympathetic white printers to get out their message. The first publishing effort under black control was a newspaper, published in New York in 1827 by John Russwurm, a Jamaica-born mulatto who was one of the first African American college graduates (Bowdoin College, 1826).“We wish to plead our own cause,” Russwurm wrote in the first issue, “too long have others spoken for us.” The paper was outspoken in defense of black rights and resolutely opposed to the growing movement to colonize free blacks in Liberia. But after two years of struggle Russwurm concluded there was no future for black people in America and joined the colonization movement and settled for the remainder of his life in Liberia. His colleague, the Rev. Samuel Cornish of New York, continued the paper and launched its successor, The Rights of All.

Philadelphia blacks were unsuccessful in launching a lasting black press. Three appeared briefly in the 1830s, The Demothsenian Shield, The Struggler, and The Elevator. There are no known surviving copies of these early Philadelphia black newspapers. |

|

The Liberator, January 1, 1831.

William Lloyd Garrison, an unsuccessful editor of several New England newspapers, found his abolitionist destiny while working with the early antislavery editor Benjamin Lundy in Baltimore in 1828 and coming into close contact with its free black community.

He sought out black leaders in the north, enjoyed especially close contacts in Philadelphia, and was swayed by their arguments for immediate emancipation, an end to racial prejudice, and a repudiation of the colonization program. His newspaper became the most famous of the antebellum antislavery papers and helped launch the American Anti-Slavery Society as an interracial movement championing abolition and equal rights for blacks. It was black energy that converted him, and his paper amplified black abolitionism by consistently publishing black writers and news of their activities. During the first decade of the paper’s existence, northern blacks were his main supporters. The emergence of a militant and biracial antislavery movement committed to equal rights was one of the most important creations of the generation of the black founders. |

![A[bsalom] J[ones] and R[ichard] A[llen], A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People during the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia in the Year 1793: And a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown upon Them in Some Late Publications (Philadelphia, 1794).](images/section6/th13-11.jpg)

![[James Forten,] “Letters from a Man of Colour, On Late Bill Before the Senate of Pennsylvania,” in Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser, April 13, 1813.](images/section6/th13-14.jpg)