A daguerreotype is more than just an image chemically transferred to a metal plate. Both the sitter and the daguerreotypist made decisions that affected what the final product looked like. Those sitting for a daguerreotype (and the vast majority of American daguerreotypes were portraits) made choices about what to wear, what studio to patronize, how large an image they could afford to purchase, whether to have hand-coloring applied, and into what type of case the image would be placed. The daguerreotypist, in turn, made decisions about lighting, posing, and the use of props in order to create the most flattering portrait possible. Shown here are various daguerreotype sizes, poses, and case styles available to consumers from Philadelphia studios.

|

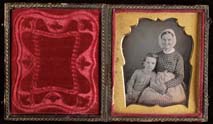

Disassembled Daguerreotype and Case, ca. 1859.

In a daguerreotype, the image appears on a highly polished and sensitized silvered copper plate. The plate is placed behind a brass mat, covered with a piece of glass. A thin brass strip known as a “preserver” helps hold the metal plate, mat, and glass together. The whole package is placed in a case which opens like a book revealing the image within. |

| |

|

|

Samuel Broadbent, attr. Wood Sisters. Whole-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1854. Gift of Wawa, Inc.

This plate is slightly smaller than the standard whole plate size (6 ½ x 8 ½″) and is a breathtakingly beautiful portrait of Caroline, Julianna, and Mary Wood, members of a prominent and prosperous Philadelphia Quaker family. The girls are framed by a wooden window opening with a crawling vine, a studio prop employed by Samuel Broadbent. The girls appear comfortable in Broadbent’s studio, perhaps because they had already sat for daguerreotype portraits on numerous previous occasions. |

| |

|

|

Collins Skylight Portraits. Unidentified Couple. Half-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1850. Gift of David Long.

Although they share an open book as a prop, this couple is not interacting with one another, with the book, or with the daguerreotypist, creating a rather odd portrait dynamic. David Collins’s brother Thomas had recently left the daguerreotype partnership, but David continued operating a studio at the prime Chestnut Street location advertised on the case’s velvet pad until 1857. |

| |

|

|

Unidentified Dickerson Family Member. Quarter-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1855.

It is possible that this daguerreotype was taken by Robert Douglass, an African-American portrait painter and daguerreotypist who had a studio on Arch Street, where he took portraits and gave daguerreotype instructions as early as the mid-1840s. The Dickerson and Douglass families moved in the same social circle among Philadelphia’s cultured, well-educated African American community. |

| |

|

|

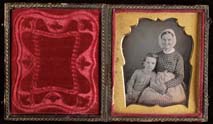

Henry Swift. Mary Barnes Swift and Grandson. Sixth-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1852.

The sixth-plate, measuring 2 ¾ by 3 ¼″, was the most popular sized plate for customers since its size made it convenient to slip out of a pocket or purse and hold in one’s hand for easy viewing. This image shows a touching lack of formality in both pose and dress, probably because the daguerreotypist was taking a picture of his mother and nephew. |

| |

|

|

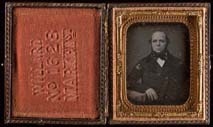

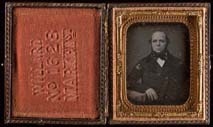

Oliver H. Willard. Unidentified Man. Ninth-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1860.

Willard was a latecomer to the Philadelphia daguerreotype profession, entering the business in the mid-1850s. At a location west of Broad Street, his studio was less centrally located than many of his competitors. |

| |

|

|

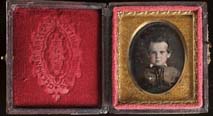

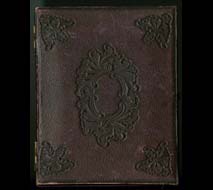

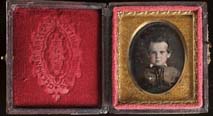

Clemons Gallery. Unidentified Boy. Sixteenth-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1853.

Although the tiny sixteenth-plate would have been the least expensive portrait size, the customer purchasing this image paid a bit more to have the child’s cheeks lightly colored. John Clemons operated a daguerreotype studio in Philadelphia at various locations from 1853 to 1860. |

| |

|

|

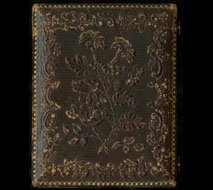

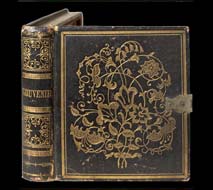

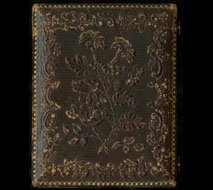

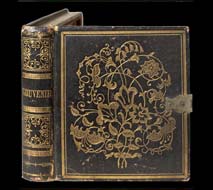

Sixth-plate Daguerreotype Case housing image by Robert N. Keely. Philadelphia, ca. 1855.

This daguerreotype is housed in a case made to resemble a beautifully bound book. With “Souvenir” stamped in gold on the spine, a gold clasp, a gold-stamped lily motif on the front and back covers, and gold edges on the text block, the daguerreotype’s housing is as eye-catching as the image itself. Unfortunately, most case makers did not mark their work. |

| |

|

|

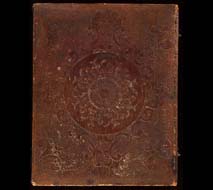

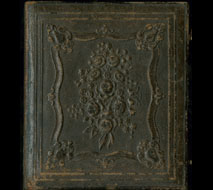

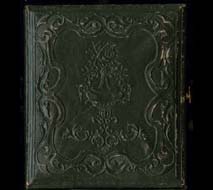

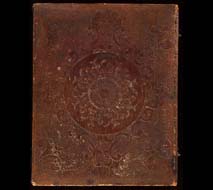

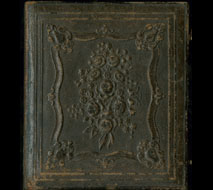

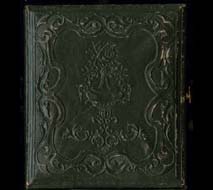

Sixth-plate Daguerreotype Case housing image by Oliver H. Willard. Philadelphia, ca. 1860. Gift of Anna S. Maier, James H. Maier, Anthony M. Maier, Marianna M. Thomas, and Cynthia C. Maier.

Wooden cases covered with embossed leather were a popular way to house daguerreotypes. With the introduction of daguerreotyping in 1839, jewel case makers, wooden box manufacturers, and others in related fields had a new outlet for their products. Decorations on the cases ranged from floral motifs, like the example shown here, to geometric designs, to elaborate scenes of buildings, animals, and people. |

| |

|

|

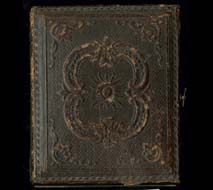

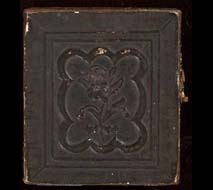

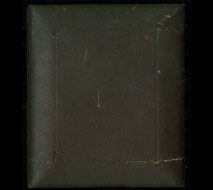

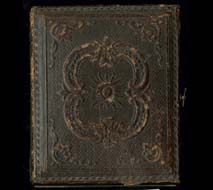

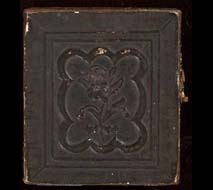

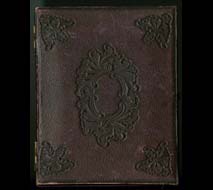

Ninth-plate Daguerreotype Case housing image of John Gummere by James E. McClees. Philadelphia, ca. 1855.

Thermoplastic cases like this example were introduced in 1852. These durable and non-porous cases helped protect the precious image inside. A number of variations of this beehive and agricultural implement motif survive. Patriotic, religious, floral, and geometric designs all appeared on thermoplastic cases. |

| |

|

|

Stereoscopic Daguerreotype of post-mortem portrait of Jonathan Williams Biddle displayed in Mascher’s Improved Stereoscope. Philadelphia, 1856. Courtesy of the Print & Picture Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia.

Inspired by an article in Scientific American, Philadelphian John F. Mascher invented a viewing device for creating a three-dimensional image out of side-by-side daguerreotypes. By June 1853, only three months after patenting the invention, the viewer was available for sale in Philadelphia, New York City, Baltimore, New Orleans, and Chicago. Scientific American praised Mascher’s viewer as “enabling us to see [loved ones] as they once were with us.” The desire to keep Philadelphia attorney Jonathan Biddle’s memory alive may have been what prompted his uncle to have this stereoscopic daguerreotype taken soon after his nephew’s death in April 1856. |