Robert Cornelius’s background in metallurgy, William Mason’s experience as an engraver, and Paul Beck Goddard’s and Walter Rogers Johnson’s knowledge of chemistry made all of these men typical of the early tinkerers with daguerreotyping. Through individual experimentation based on information gained from published accounts and attendance at lectures and demonstrations, these early daguerreotypists mastered and improved Daguerre’s process.

|

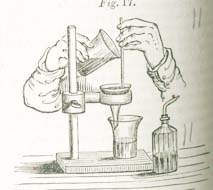

Louis Daguerre. History and Practice of Photogenic Drawing. Translated by J. S. Memes. London: Smith Elder and Company, 1839.

Memes dated the preface of this book September 13, 1839, only a few weeks after Daguerre’s discovery was made public. The Library Company acquired this copy around the time of its publication. |

| |

|

|

Joseph Saxton. View of Central High School. Philadelphia, September or October, 1839. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Saxton took this view from the U.S. Mint, where he was employed, possibly on a plate provided by Robert Cornelius. Credited as the oldest extant American daguerreotype, the original is in the collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. |

| |

|

|

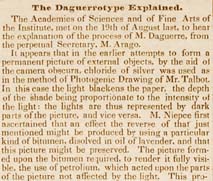

“The Daguerreotype Explained,” in United States Gazette, September 25, 1839.

University of Pennsylvania professor Alexander Dallas Bache provided this factual account of the basic steps to making a daguerreotype, the first mention of daguerreotyping to appear in a Philadelphia newspaper. |

| |

|

|

Walter Rogers Johnson. Ezra Otis Kendall. Sixth-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, October or November 1839. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

In late December 1839 and in February 1840 Walter Johnson gave public lectures and daguerreotype demonstrations in Philadelphia. Although a pioneering daguerreotypist in his own right, Johnson modestly drew attention to the work of his peers. “My own are not by any means the only pieces which have been produced in this country,” Johnson stated in the National Gazette. “It is due to Mr. Joseph Saxton, Dr. Paul B. Goddard, Mr. Robert Cornelius and Mr. James Swain, to mention that each has made a number of successful attempts in the execution of the process of M. Daguerre.” This portrait of Ezra Kendall, a teacher of mathematics and astronomy at Philadelphia’s Central High School, may be the earliest daguerreotype portrait taken in Philadelphia. |

| |

|

|

Paul Beck Goddard. View from the roof of the University of Pennsylvania. Half-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1839. Courtesy of the Museum Collections of The Franklin Institute, Inc., Philadelphia, Pa.

Philadelphia physician and chemist Paul Beck Goddard’s interest was piqued by news of Daguerre’s successful experiments. Goddard’s personal library included at least five French pamphlets detailing Daguerre’s work. Goddard’s discovery that sensitizing the daguerreotype plate with bromine drastically reduced exposure times to as little as ten to sixty seconds made commercial portraiture a realistic possibility, and he became a silent partner in Robert Cornelius’s studio. This daguerreotype shows the view from the University of Pennsylvania when it was located on 9th Street between Chestnut and Market Streets. |

| |

|

|

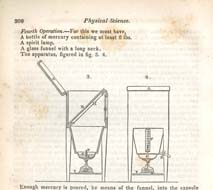

“Practical Description of the Process called the Daguerreotype,” in the Journal of the Franklin Institute, November 1839.

University of Pennsylvania professor of chemistry and Franklin Institute member John Fries Frazer translated Daguerre’s detailed instructions on how to make a daguerreotype into English for the Journal’s November issue, but references to Daguerre’s work appeared as early as September 1839. Copies of the Journal went to subscribers as far away as Florida and New Orleans as well as to many Philadelphia institutions including the American Philosophical Society, the Mercantile Library, the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, and the West Philadelphia Institute, ensuring that news of Daguerre’s discovery and later improvements would spread far and wide. |

| |

|

|

Robert Cornelius. Robert Davidson. Sixth-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, May 1840.

Davidson, a Philadelphia exchange broker, sat for this daguerreotype during Cornelius’s first month of business, making it the earliest in our collection. Perhaps Davidson had seen the recent Daily Chronicle article assuring readers of the ease of having one’s daguerreotype taken. “All you have to do,” stated the article, “is place yourself in an easy, well-cushioned chair, assume the position in which you desire to be perpetuated, and look steadfastly at a given object for the matter of half a minute.” Cornelius probably charged Davidson $5.00 for this image. |

| |

|

|

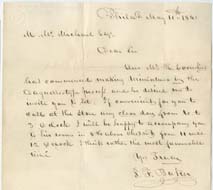

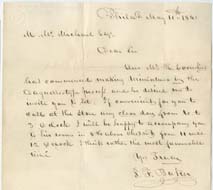

Letter Soliciting Business for Robert Cornelius’s Studio, May 11, 1840. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Robert Cornelius opened one of America’s first (and Philadelphia’s first) daguerreotype studios on May 6, 1840, after more than seven months of experimentation. He had obtained a lens from the city’s leading optician John McAllister, built a camera, and in October 1839 purchased seven pounds of “Rich Plate for the daguerreotype business.” John McAllister became Cornelius’s first paying customer. In this letter, Cornelius’s brother-in-law and future partner in the lamp manufacturing business encourages journalist and future Philadelphia mayor, Morton McMichael, to visit the studio for a portrait. In addition to personal solicitations, Cornelius took out many newspaper advertisements touting his new venture. His promotional efforts likely paid off since only a month after the studio’s opening, the United States Gazette reported being “astonished at the excellent likenesses of many well known citizens which Mr. Cornelius has taken.” |

| |

|

|

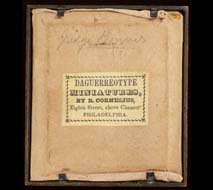

Robert Cornelius Studio Label, ca. 1840.

Cornelius attached this paper label to the back of his framed daguerreotypes. |

| |

|

|

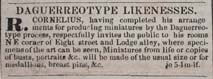

“Daguerreotype Likenesses,” in North American and Daily Advertiser, June 12, 1840. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Only a month after opening his studio, Robert Cornelius ran advertisements in at least two different Philadelphia newspapers inviting the public’s patronage. |

| |

|

|

Robert Cornelius. John Bouvier. Sixth-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1840.

After serving an apprenticeship in the printing and bookselling business, Bouvier, a French immigrant, opened his own printing shop. He also became a member of the Pennsylvania bar in 1818. By the time of this daguerreotype, Bouvier was a municipal judge and had just published a legal dictionary which became a classic in the field. Bouvier’s portrait, like many of Cornelius’s early daguerreotypes, is housed in a brass frame, probably made in the family’s lamp manufactory. |

| |

|

|

Robert Cornelius. Grandma Toppan. Sixth-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1841.

Little is known about this sitter who most likely had her portrait taken at Cornelius’s new Market Street studio, into which he moved in June 1841. By then, Cornelius had purchased a new lens which permitted him to shoot half-length poses and had begun to place the finished plates in simple wood and leather cases. |

| |

|

|

Robert Cornelius. Martin Hans Boyé. Sixth-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, December 1843. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Although Robert Cornelius apparently closed his studio in 1842 and returned to his family’s brass lamp manufacturing business, he did not completely turn his back on daguerreotyping. In late 1843 he took several portraits of Boyé, who along with Paul Goddard worked with Dr. Robert Hare, a University of Pennsylvania chemistry professor. The portions of these daguerreotypes showing Boyé’s hands and chemical apparatus were reproduced as engraved illustrations in Boyé’s article on “analysis” in The Encyclopedia of Chemistry (1850). |

| |

|

|

James Curtis Booth. The Encyclopedia of Chemistry, Practical and Theoretical. Philadelphia: Henry C. Baird, 1850. Reproduction. |

| |

|

|

William G. Mason. Chestnut Street at Strawberry Alley. Sixth-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1843. Gift of John A. McAllister.

Mason, an engraver and amateur daguerreotypist, took this image outside his Chestnut Street shop. Although he never had his own studio, Mason acted briefly as a Philadelphia agent for a New York City daguerreotype plate maker. |

| |

|

|

| |

|

1. Daguerreotype Camera, 1839. Courtesy of the Museum Collections of The Franklin Institute, Inc., Philadelphia, Pa.

Scientific instrument maker Joaquim Bishop constructed this camera for physician and chemist Paul Beck Goddard. Goddard’s professional responsibilities, however, soon prevented him from actively pursuing daguerreotyping. According to late-19th-century antiquarian Julius Sachse, Goddard sold this camera to prominent Philadelphia engraver John Sartain, who reportedly took only one successful daguerreotype, an image of the Masonic Hall, which was later lost.

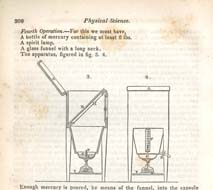

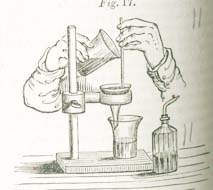

2. Daguerreotype Developing Box, 1839. Courtesy of the Museum Collections of The Franklin Institute, Inc., Philadelphia, Pa.

After exposure in a camera, a metal plate was placed in a developing box. This particular box is believed to have been made by Joaquim Bishop for Paul Beck Goddard. Through the action of heated mercury in the box, the latent image on the plate became visible in two to four minutes. The plate then went through a fixing bath, a rinsing, and then gilding to strengthen the image’s tones and make it more durable on the plate. With one final rinse, the plate was ready for hand-coloring, if desired, and placement in a case.

3. Daguerreotype Plate Holding Box, ca. 1850. Courtesy of the Museum Collections of The Franklin Institute, Inc., Philadelphia, Pa.

This wooden box holds the silvered copper plates on which daguerreotyped images would appear. The box, along with the sensitizing box, pumice, and rouge, all exhibited here, came to the Franklin Institute from the estate of Philadelphia daguerreotypist David C. Collins in 1939, to mark the 100th anniversary of the invention of the daguerreotype.

4. Glass Bottles of Rouge and Pumice, ca. 1850. Courtesy of the Museum Collections of The Franklin Institute, Inc., Philadelphia, Pa.

Pumice, or more accurately rotten stone, was mixed with water and alcohol, and then applied in a circular motion as an abrasive in polishing a daguerreotype plate. Finally the plate was buffed with powdered rouge followed by lampblack.

5. Daguerreotype Sensitizing Box, ca. 1850. Courtesy of the Museum Collections of The Franklin Institute, Inc., Philadelphia, Pa.

Cleaned, polished, and buffed plates were made light- sensitive by exposure to various chemicals in a sensitizing box. Nearly all the chemicals in this process –chlorine, iodine, bromine, potassium cyanide, and mercury – were toxic, a fact at least some daguerreotypists suspected. The February 15, 1855, issue of Humphrey’s Journal of the Daguerreotype & Photographic Arts included a survey requesting information from daguerreotypists about what effects exposure to “vapors of iodine” had on their health. |

| |

|