Creating a Profession

The success of the early experimenters in reducing the exposure time paved the way for daguerreotyping as a profession. With the basic technology mastered, daguerreotypists could turn to creating a market for their works. As America’s fourth largest city, Philadelphia had a large enough population to support this new profession. Public exhibitions and advertising were two ways to introduce the public to and spark their interest in daguerreotypes. By 1846 Philadelphia supported over a dozen daguerreotype studios including those of the Langenheim brothers and Montgomery P. Simons whose careers would extend far beyond the daguerreian era.

Click images below for larger view in a new window.

W. & F. Langenheim. Exhibition of the Institute of American Manufactures at the Chinese Museum, October 1844. Salted paper print of a daguerreotype, Philadelphia, ca. 1855. Gift of John A. McAllister.German immigrant brothers William and Frederick Langenheim opened their Philadelphia studio on January 1, 1841, launching successful photographic careers that lasted until the mid 1870s. 1844 was the first year their daguerreotypes won an award at the Franklin Institute-sponsored exhibition. |

|

Report of the Committee on Exhibitions in Journal of the Franklin Institute, December 1844.Daguerreotypes were first exhibited at the Franklin Institute’s American Manufactures exhibition in 1840, when Joseph E. Parker, a Philadelphia dentist, won a certificate of honorable mention. Philadelphia daguerreotypists soon recognized the value of exhibiting as more of their colleagues entered the competition. “Rely upon it,” declared a speaker at the close of the Franklin Institute’s Twelfth Exhibition in 1842. “These exhibitions and the premiums awarded at them, have a powerful action upon the consumer, the vender [sic], and the manufacturer, and through them upon the arts.” |

|

Philadelphia Mercantile Directory, or, Business Man’s Guide. Philadelphia: H. Orr, 1846. Gift of Charles A. Poulson.Montgomery P. Simons may have taken out this full-page advertisement to celebrate ownership of his own studio following the recent dissolution of his partnership with Thomas Collins. The other daguerreotypists in the directory have opted for more modest advertisements, but all are eye-catching with their decorative borders and bold red printing. |

|

W. & F. Langenheim. Unidentified Woman. Sixth-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1845.The Langenheim brothers opened a studio in Philadelphia’s Merchants’ Exchange building, an ideal location with its daily turnover of people visiting its commodities exchange, reading room, offices, post office, and restaurant. By the time this woman sat for the Langenheims in the mid 1840s, their studio was well established. Cash books covering five weeks during May and June 1845 indicate that the studio took 269 daguerreotypes for a total of $1,160.75, approximately double the amount they had made in a similar period the previous year. |

|

W. & F. Langenheim. North-east corner of Third & Dock Street. Girard Bank, at the time the latter was occupied by the military during the riots May 9, 1844. Oversize half-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, 1844. Gift of John A. McAllister.A crowd of men and boys gathered in front of the First Bank of the United States, which served as the militia’s temporary headquarters during Philadelphia’s anti-Catholic riots. The excitement happening right outside the window of the Langenheim brothers’ Merchants’ Exchange studio was too important not to be recorded for posterity, and they used their camera to capture Philadelphia’s earliest “news photograph.” The use of a reversing mirror or prism mounted in front of the lens ensured that signs on the nearby buildings would read correctly. Most daguerreotypes are laterally reversed. |

|

W. & F. Langenheim. Caroline and Mary Wood. Half-plate daguerreotype, Philadelphia, ca. 1846. Gift of Wawa, Inc.This delicately hand-colored portrait may have been taken during the Wood family’s May 1, 1846, visit to the Langenheim studio. A number of different and competing techniques existed for coloring daguerreotypes. In early 1846 Frederick Langenheim bought the American patent rights on a coloring technique invented by a Swiss daguerreotypist. Another Philadelphia daguerreotypist, John J. E. Mayall, had a patent on a similar coloring process, launching a fierce competition between the men. |

|

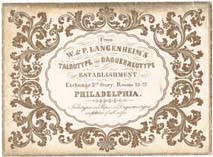

Langenheim Advertising Envelope, ca. 1849.In 1849 the Langenheim brothers purchased the American patent rights to the talbotype, a paper negative process named after its British inventor William Henry Fox Talbot. This advertising envelope with its Merchants’ Exchange address quickly became obsolete since in the autumn of 1850 the Langenheims moved their studio to a more centrally located block of Chestnut Street. After the move they continued to give equal prominence to both their talbotype and daguerreotype business, advertising that “talbotype portraits can be procured from daguerreotypes, in all the different sizes, thus affording a desirable opportunity to procure life like portraits of deceased persons.” |

|

Montgomery P. Simons. Julianna Randolph Wood. Quarter-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1847. Gift of Radclyffe F. and Maria M. Thompson.Although posing with a book is a common portraiture convention, it may have been particularly appropriate for Julianna R. Wood. In her memoirs, she fondly recalled that during her early years of marriage to Richard Wood, “we read together in the evening the entire Bible regularly through, and also many other works.” Juliana sat several times for daguerreotypes, including at least one other session at Simons’s Chestnut Street studio. |

|

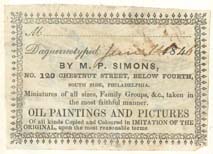

Montgomery P. Simons Studio Label, 1846. |

|

Montgomery P. Simons. Two Unidentified Young Women. Half-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1846.It is not known from whom Simons learned daguerreotyping, but he reminisced about visiting Robert Cornelius’s and the Langenheim brothers’ studios in the early 1840s and being fascinated by the process. Upon opening his own studio in 1846, he was able to attract famous sitters including Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and Jefferson Davis, as well as more ordinary Philadelphians. The unknown sitters in this daguerreotype present an interesting contrast to one another in both dress and demeanor. |

|

Montgomery P. Simons. Photography in a Nut Shell. Philadelphia: King & Baird, 1858. Gift of John A. McAllister.In an advertisement, Philadelphia daguerreotypist Marcus Root praised this book written by his competitor Montgomery Simons. Writing at the end of the daguerreian era, Simons clung to the belief that neither ambrotypes nor paper prints would ever take the place of daguerreotypes. Simons, however, did embrace paper photography later in his career. |

|

Please click on each image in the below frame for a larger view. |

|

|

|

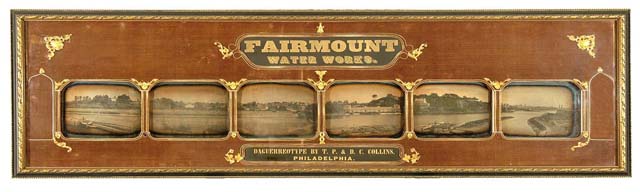

Thomas P. and David C. Collins. Panoramic View of Fairmount Water Works. Six half-plate daguerreotypes. Philadelphia, ca. 1846. Courtesy of the Museum Collections of The Franklin Institute, Inc., Philadelphia, Pa.The view around the Fairmount Waterworks has always attracted artists, so it is not surprising that daguerreotypists also tried to capture the scene. Philadelphia daguerreotypist John J. E. Mayall made a panoramic view, as did Cincinnati daguerreotypist William Southgate Porter. In addition to the waterworks building seen from the west bank of the Schuylkill, the Collins brothers’ panorama also includes the Schuylkill Navigation Company’s canal and the Fairmount Suspension Bridge down river. This masterpiece is the “superior landscape daguerreotype” for which the brothers won a silver medal at the 1846 American Institute Fair held in New York City. |

|