A Walk along Chestnut Street

“Among the most notable things in Chestnut-street,” declared The New York Tribune in late 1848, “are the multitudinous daguerreotype establishments, with the walls of the entrances and the passage-ways stuccoed with these transfixed reflections of substantial flesh and blood.” As the blocks around Independence Hall filled with hotels, banks, and stores, daguerreotype studios could rely on a steady stream of potential customers moving through the area.Such close proximity among practitioners also led to intense competition as daguerreotypists sought to elevate the quality of their work above that of their neighbors.

Click images below for larger view in a new window.

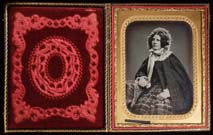

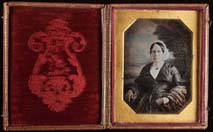

D. C. Collins and Company. Margaret Griscom McCord Smith. Half-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1854.The Collins brothers opened their Chestnut Street studio in June 1846, only five days after Marcus Root’s nearby gallery opened. Although Thomas Collins privately expressed his annoyance at customers who visited their studio only because they grew tired of waiting at Root’s popular establishment, the Collins studio took more than 9,500 daguerreotypes over a five-year period, certainly not indicative of a struggling business. After Thomas left Philadelphia, David continued on his own, and his studio work includes this lovely daguerreotype of Betsy Ross’s great-niece. |

|

North American and United State Gazette, February 12, 1848. |

|

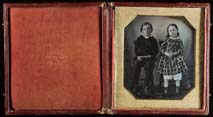

Van Loan & Mayall. Unidentified Boy and Girl. Oversize quarter-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1846.Englishmen Samuel Van Loan and John Jabez Edwin Mayall formed a short-lived daguerreotype partnership in Philadelphia in 1845-1846. Van Loan probably learned daguerreotyping in England, while Mayall studied under Martin Hans Boyé and Paul Beck Goddard in Philadelphia. In 1846 Marcus Root took over Van Loan and Mayall’s studio at 140 Chestnut Street and Mayall returned to England, where he opened the American Daguerreotype Institution in London, hoping to capitalize on the perceived superiority of American daguerreotypes. |

|

Van Loan Gallery. Mary Housekeeper. Sixth-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1852.In the early 1850s Samuel Van Loan worked with C. H. Housekeeper, who identified himself in the 1850 census as an artist. Undoubtedly this little girl, who is rather casually posed in front of a stylized scenic backdrop, was a relative of Van Loan’s partner. |

|

Van Loan Gallery. Unidentified Family Group. Half-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1850.Samuel Van Loan’s advertisement urged customers to obtain a daguerreotype because “the connecting link between the past and the future is with you and yours.” That sentiment is embodied by this multi-generational family portrait with the youngest family member propped up between its great-grandmother and grandmother. |

|

|

|

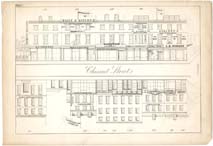

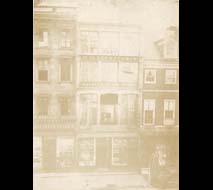

Julio H. Rae. Julio H. Rae’s Philadelphia Pictorial Directory & Panoramic Advertiser. Plate 7 and corresponding page. Philadelphia: Julio H. Rae, 1851. Gift of J. Fisher.Rae’s directory documented the 200 to 900 blocks of Chestnut Street, an area filled with daguerreotype studios. By subscribing to the directory, one’s business would be identified in the façade image of that block and a corresponding advertisement would be included on the adjoining page. In this portion of the 400 block, Marcus Root, Van Loan & Co., and Broadbent & Co. are all represented. Other plates in the volume indicate that D. C. Collins and Company, Frederick De Bourg Richards, Thomas Ennis, and Langdon & Company also took advantage of this advertising opportunity. |

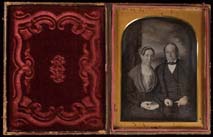

S. G. Hewes. Unidentified Couple. Half-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1852.Sally Garrett Hewes, one of the few female daguerreotypists in Philadelphia, learned the art from either her brother, Wilmington daguerreotypist Ellwood Garrett, or Samuel Broadbent, the Philadelphia daguerreotypist with whom she worked starting in 1851. As a widow with three young children and few financial resources, Hewes probably turned to daguerreotyping for economic reasons, but the quality of this image indicates that she had a genuine talent for her chosen profession. Her gender was clearly identified in newspaper advertisements for Broadbent & Co., perhaps an effort to capitalize on the novelty of a female daguerreotypist. |

|

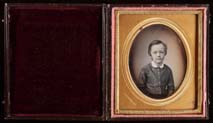

Samuel Broadbent. Walter Wood. Sixth-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1858. Gift of Wawa, Inc.Although by the late 1850s Broadbent was undoubtedly offering other photographic formats besides daguerreotypes, the Wood family of Philadelphia chose to have their young son documented the same way as their older children. The plain case and simple mat style suited their Quaker beliefs. |

|

Samuel Broadbent, attr. Miriam Good. Quarter-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1851.Samuel Broadbent initially trained as a portrait painter, and he frequently employed a painted landscape backdrop for his daguerreotypes. “Beautiful Landscape, Picturesque or Plain Backgrounds, at the option of the Sitter,” read an 1853 Broadbent & Co. newspaper advertisement. In the 1860s Broadbent returned to painting while still maintaining a photographic studio with various partners. |

|

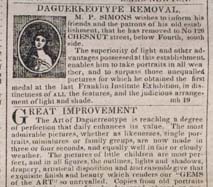

Daguerreotypists’ newspaper advertisements in the November 3, 1846, issue of North American. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.Four Chestnut Street daguerreotypists compete for attention on just one newspaper page. By including an image of a daguerreotype, Montgomery P. Simons’s advertisement is certainly the most eye-catching. |

|

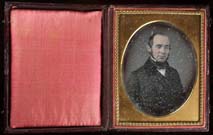

P. B. Marvin. Unidentified Man. Quarter-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1855.Marvin had a Chestnut Street studio for five years during the 1850s, but little is known about his career. The pride he took in his work, however, is evident in his unusual decision to etch his name and address into the daguerreotype plate. |

|

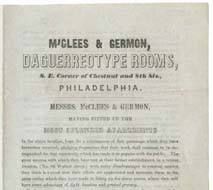

Advertisement for McClees & Germon Daguerreotype Rooms. Philadelphia: G. S. Harris, 1848. Gift of David Doret.Issued to announce McClees & Germon’s recent studio relocation, this advertisement invited the public to stop in any time between 8 a.m. and dark at the studio patronized “by the best Painters and Engravers in the city.” McClees and Germon had become partners in 1846 when James McClees ended his business relationship with Montgomery Simons, and rather than follow his initial plan of joining Thomas P. Collins’s studio, instead joined forces with his friend Washington Lafayette Germon, who was struggling in an unsuccessful daguerreotype business with lithographer John Frampton Watson. |

|

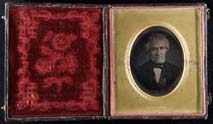

McClees & Germon. John Bouvier. Sixth-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1850.This daguerreotype of Philadelphia judge and author John Bouvier was taken not long before his death in 1851. Bouvier is known to have sat for at least one other daguerreotype, a portrait by Robert Cornelius taken a decade earlier and also on display in this exhibition. |

|

McClees & Germon. Two Unidentified Women. Sixth-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1850.In addition to portraits such as the lovely one exhibited here, the partners advertised that they took views of “public buildings, store fronts, &c.” Beginning in 1848 McClees & Germon’s daguerreotype work received recognition in the Franklin Institute’s exhibitions. The partners also entered into a national daguerreotype competition in 1852, losing out to two New York City daguerreotypists. |

|

McClees & Germon Daguerreotype Studio. Salted paper print. Philadelphia, ca. 1853. Gift of John A. McAllister.The two partners, visible in the large second floor window, operated this studio in the 700 block of Chestnut Street for about two years. The continued growth of their business prompted a move to an even larger space a block east on Chestnut Street. Despite their success, the men amicably dissolved their partnership by 1855. |

|

Frederick De Bourg Richards. Charlotte Conarroe and Daughter Ellen. Quarter-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1857. Gift of Hugh P. Brinton.Frederick De Bourg Richards continued his career as a painter even after he became a professional daguerreotypist around 1846. Richards’s ties to Philadelphia’s artistic community may have influenced the Conarroe women’s choice of what studio to patronize since the family patriarch, George, was also an artist. “Richards is a man of artistic sentiment,” declared The Photographic and Fine Art Journal in April 1856, “and it would be indeed strange if he were second to any in the art he has espoused.” Richards’s daguerreotypes consistently won top honors at the Franklin Institute’s exhibitions throughout the 1850s despite the controversy stirred up by Marcus Root’s assertion that Richards in 1853 won for the largest, not the best, daguerreotype. |

|

“The daguerreotype art we believe has been brought to as high a state here [Chestnut Street in Philadelphia] as in any other place, and the male portraits are generally very authentic and acceptable likenesses of the originals. But with the ladies the case is different. We profess that we have never yet seen a daguerreotype of a lady which gave us any sort of satisfaction. The shadows and the strong points of the face alone seem to stick to the magic plate; while the false focus of the arms and hands always presents those indispensable elements of female grace in an enlarged and awkward shape. While the exquisite and indescribable softness and grace of the features are invariably lost, the hands and arms constantly appear as if they had been cooked and had swelled in boiling. If we were a pretty woman they should take our life sooner than our daguerreotype. These daguerreotype saloons are, however, constantly crowded by ladies, chiefly from the country who go away happy, with a miniature of their precious selves safely stowed in their work-bags, and which was painted in a minute and cost a dollar.”

“Philadelphia in Slices”

New York Tribune, December 28, 1848