Marcus Aurelius Root

More than any other Philadelphia daguerreotypist, Marcus A. Root strove to raise the quality of work produced by daguerreotypists and the public’s appreciation and recognition of that work as art. Root exhibited his daguerreotypes both nationally and internationally and wrote extensively about the history and aesthetics of photography.

Click images below for larger view in a new window.

Marcus A. Root. Persifor Frazer. Half-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1852.Root wrote extensively about the need to create a comfortable environment for sitters, so that those entering a studio “may inhale a spirit which shall illuminate their faces with the expression desired.” He recommended filling the lobby with paintings, sculpture, and books so that customers would elevate their thoughts prior to sitting. To reveal the lively nature of a spirited boy, Root provided Persifor with an 18th-century costume, complete with sword and wig. |

|

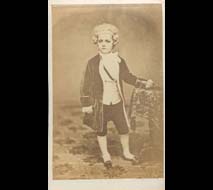

Montgomery P. Simons. Persifor Frazer. Albumen print carte-de-visite. Philadelphia, ca. 1857. Gift of Rebecca Norris.A major drawback of the daguerreotype process was the lack of a negative that would allow multiple copies to be made from one exposure. When the customer desired multiple images, the daguerreotypist took several different shots, as Root did during his session with young Persifor Frazer. Some years later, Simons copied a different daguerreotype than the one displayed here, resulting in this paper print. |

|

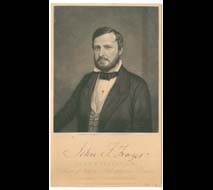

Marcus A. Root. John Fries Frazer. Half-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1852.John Frazer, University of Pennsylvania professor of natural philosophy and chemistry and the father of Persifor (whose daguerreotype is also shown in this case), was intrigued by daguerreotypes from their earliest days. He translated Louis Daguerre’s instructions on how to take a daguerreotype for publication in the Journal of the Franklin Institute in 1839, and he donated a copy of Daguerre’s book to the Franklin Institute’s library in 1842. John Frazer is credited with creating a daguerreotype himself, although it was later lost. |

|

Adam B. Walter. John Fries Frazer. Engraving. Philadelphia, ca. 1852. Gift of John A. McAllister.Marcus Root’s daguerreotype of John Frazer served as the basis for this engraving. Engravers frequently relied on daguerreotype images in order to produce multiple copies of an image. |

|

Marcus A. Root. Captain George C. Stouffer, Half-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1854. Courtesy of the Print & Picture Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia.Philadelphia’s major daguerreotype studios competed to obtain portraits of celebrities passing through the city. Celebrities known to have sat for Root include Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and Edgar Allan Poe. Although not as famous as those men, Captain Stouffer was hailed as a national hero for leading the rescue effort to save the hundreds of passengers on board the wrecked steamship San Francisco in January 1854. The United States Congress awarded Stouffer a gold medal and $7,500 for his good work. |

|

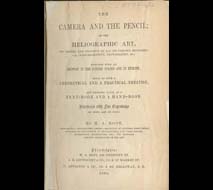

Marcus Root. The Camera and the Pencil, or, The Heliographic Art. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1864.“Why (I queried with myself) should not Heliography be placed beside Painting and Sculpture, and the Camera be held in like honor with the Pencil and the Chisel?” wrote Root in this book’s introduction. According to Root, a daguerreotypist’s studio should be “a temple of beauty and grandeur,” an appropriate setting in which an artist could create images worthy of the designation of fine art. For more than a decade Root wrote on these themes, submitting numerous articles to the Photographic Art Journal and writing the book shown here, which was intended to be published as a two-volume set. The second volume, however, was destroyed in a fire at the printer’s shop. |

|

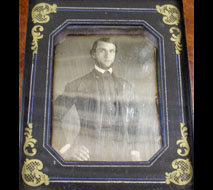

Marcus Root. Caleb C. Roberts. Quarter-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1847. Courtesy of the Museum Collections of The Franklin Institute, Inc., Philadelphia, Pa.A later inscription on the back of this piece declared that Root won first prize at the 1847 Franklin Institute exhibition with this daguerreotype, but the judges’ report indicated that they chose to not award any prizes for daguerreotypes that year. Probably much to Root’s distress, the judges that year also wrote that they did not consider daguerreotypes “as strictly belonging to the Fine Arts” but conceded that “good collections of specimens are attractive and add to the interest of our exhibitions.” Whether a prize winner or not, Root took a fine portrait of the young Philadelphia merchant Caleb Roberts confidently gazing at the camera with hand on hip. |

|

Root’s Gallery. Unidentified Militia Man. Whole-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1848.Although the sitter’s identity is unknown, Root has captured his air of power and authority in this striking portrait. |

|

Advertising broadside for Marcus Root, Philadelphia, ca. 1852.Marcus Root claimed to have spent $20,000 on advertising during his career, and the numerous newspaper announcements, broadsides, and other advertising ephemera in existence today make his assertion seem plausible. Here he utilized testimonials from well-known artists to bolster his claim that daguerreotyping belonged in the realm of fine arts. |

|

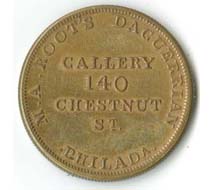

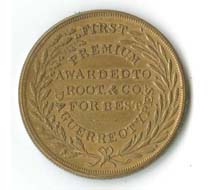

Advertising Token for M. A. Root Daguerrian Gallery, ca. 1850. Gift of Christine Dallett Smith.Marcus Root widely exhibited his daguerreotypes. In addition to regularly displaying them at the Franklin Institute’s fairs, he also exhibited in London in 1851 and 1854, and was the only Philadelphia daguerreotypist whose work appeared in the Fifth Exhibition of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association in 1847 and New York’s 1853 Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations. The first premium touted by this token may refer to Root’s award “for unrivalled excellence” given at the Franklin Institute’s 1849 exhibition. |

|

V. B. Palmer’s American Newspaper Subscription and Advertising Agency. Advertising Copy for M. A. Root’s Gallery of Daguerreotypes, 140 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, 1847. Gift of David Doret.This printer’s proof provided text for two separate newspaper advertisements. The one on the left extolled Root’s daguerreotypes and ran every other week for six months, while the one on the right urged visitors coming to Philadelphia during the Christmas holiday season to patronize Root’s gallery. |

|

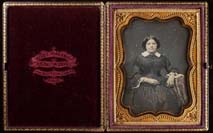

George S. Cook. Unidentified Woman. Quarter-plate daguerreotype. Philadelphia, ca. 1857.In 1856 Marcus Root had closed his Philadelphia gallery and made plans to open a New York City gallery when disaster struck. Critically injured in a horrific train accident, Root spent the late 1850s recovering from his injuries and writing The Camera and the Pencil. Daguerreian George Cook became either a partner of Root or the owner of the business, which continued to be known as Root’s Gallery. |

|

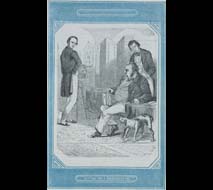

T. S. Arthur. “Sitting for a Daguerreotype,” in Sketches of Life and Character. Philadelphia: J. W. Bradley, 1850.This engraving illustrated the fictional satirical story of a farmer who came to Philadelphia to have his daguerreotype taken for his family. He visited Marcus Root’s gallery but was so disturbed by the unfamiliar surroundings and apparatus that he bolted from the studio and refused to return. |