Supplying the Profession

Philadelphia daguerreotypists needed high quality supplies in order to produce first-rate daguerreotypes. Initially, American practitioners relied on imported goods, but domestic manufacturers soon rose to meet the need. Foreign and domestic supplies could be purchased through Philadelphia wholesalers and some items such as cases were produced in the city.

“Our brother in law, Mr. Voightlander in Vienna, appointed us his Agents, for the Sale of his Daguerreotype and other optical instruments. We have sold more than 1500 of them, and this has made us more or less acquainted with every operator in the Country. This would not only show that we are acquainted with the way of opening a market to something or real merit, but it will also show, how extensively the Daguerreotype has been fostered and appreciated in this country, for such a number of instruments could never have been sold by us, if the operators had no need of them and the public had not patronized them.”

Letter from W. & F. Langenheim to William Henry Fox Talbot, February 5, 1849. Collection of the National Museum Photography Film & Television (Bradford, UK)

Click images below for larger view in a new window.

South Side of Chestnut Street. Albumen print of an 1843 daguerreotype by William G. Mason, Philadelphia, 1862. Gift of John A. McAllister.John McAllister’s optician’s shop was prominently featured in Mason’s view of Chestnut Street. McAllister was not only Robert Cornelius’s first paying customer, he was also one of the city’s earliest suppliers of daguerreotype goods. An August 12, 1843, newspaper advertisement announced that he had “just received a few sets of Daguerreotype Lenses according to Dr. Goddard’s arrangements, for sale low,” as well as “plates of various sizes – French and American.” |

|

Henry A. Eickmeyer. Ninth-plate Case housing a daguerreotype of Sallie Sherrel Bonnell Houston. Philadelphia, 1856. Gift of Charlotte Dallett.Eickmeyer first appeared as a daguerreotype case maker in Philadelphia city directories in 1852. He received a patent for this distinctive style case in 1855 and marked his cases with that designation on the lower inside margin of the front cover. The daguerreotype housed in this case celebrates the recent marriage of Sallie Bonnell to Henry Howard Houston, a prominent Philadelphia businessman. |

|

Robert Jennings. Sixth-plate Daguerreotype Case. Philadelphia, ca. 1852.Robert Jennings was listed as a case maker in Philadelphia directories in the early 1850s, although at a different location than the one noted on this paper label. By the mid 1850s he had switched careers and become a veterinary surgeon. Few examples exist of cases with maker’s labels. |

|

Montgomery P. Simons. Quarter-plate Daguerreotype Case. Philadelphia, ca. 1845.From about 1843 through 1847 Montgomery Simons made daguerreotype cases while also practicing daguerreotyping both on his own and in partnership with others. Simons produced plain, floral, and geometric cases as well as the scenic design of this case. |

|

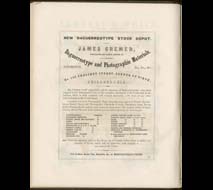

“James Cremer, Wholesale and Retail Dealer in Daguerreotype and Photographic Materials,” in Byram’s Illustrated Business Directory. Philadelphia: J. H. Byram, 1856.After working as a daguerreian supplier in New England and New York City, Cremer opened a supply depot in Philadelphia in 1855 serving both daguerreotypists and those working with paper photography. Conveniently located on Chestnut Street, Cremer offered goods including cameras, cases, plates, and chemicals. |

|

Daguerreotype Plate Buffer with James Cremer Label, ca. 1855. Courtesy of the Museum Collections of The Franklin Institute, Inc., Philadelphia, Pa.After cleaning and polishing, obtaining a well-buffed plate was the next essential step in the creation of a pleasing daguerreotype. “The point to be aimed at is, the production of a surface of such exquisite polish as to be itself invisible, like the surface of a mirror,” wrote S. D. Humphreys in American Hand Book of the Daguerreotype (New York, 1853). “In all cases, very light and long continued buffing is productive of the greater success, since by that means a more perfect polish can be obtained.” |

|

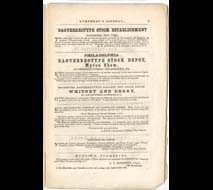

“Myron Shew, Philadelphia Daguerreotype Stock Depot Advertisement,” in Humphrey’s Journal of the Daguerreotype & Photographic Arts, February 15, 1855.Perhaps realizing that competition was about to increase with the establishment of James Cremer’s supply depot, Shew placed this advertisement in Humphrey’s Journal, the first periodical in the world devoted strictly to photography and reaching approximately 2,000 subscribers. With goods more readily available locally, daguerreotypists would no longer have to travel to New York City, as James McClees did in September 1851, to purchase his “winter’s supply of materials.” |