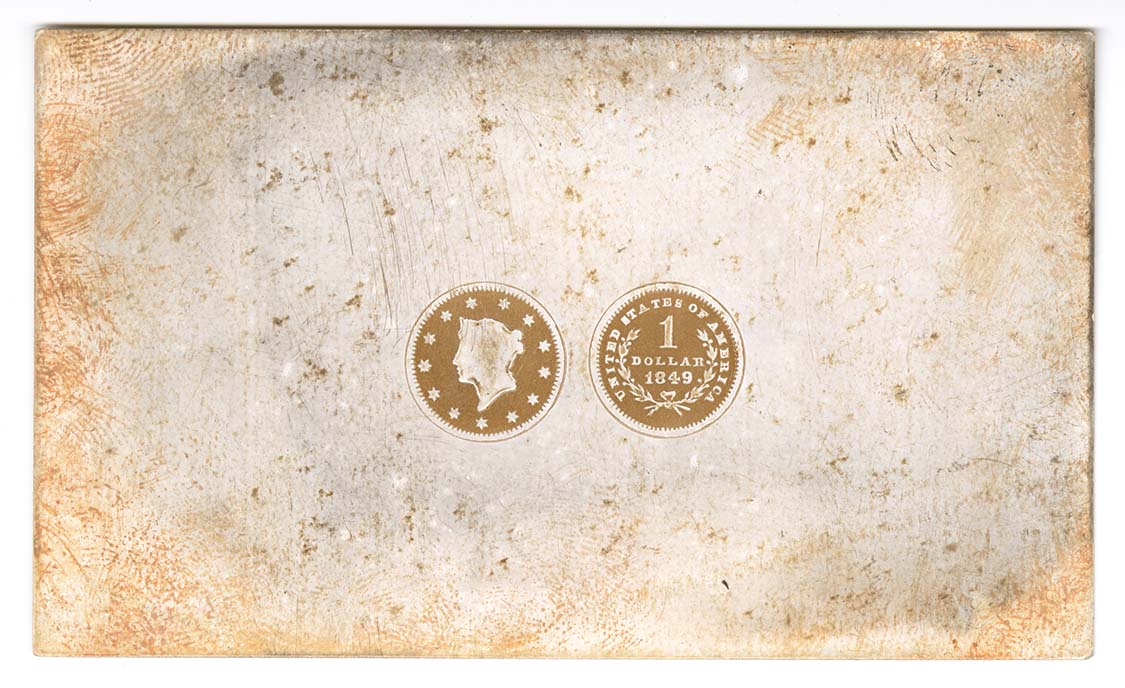

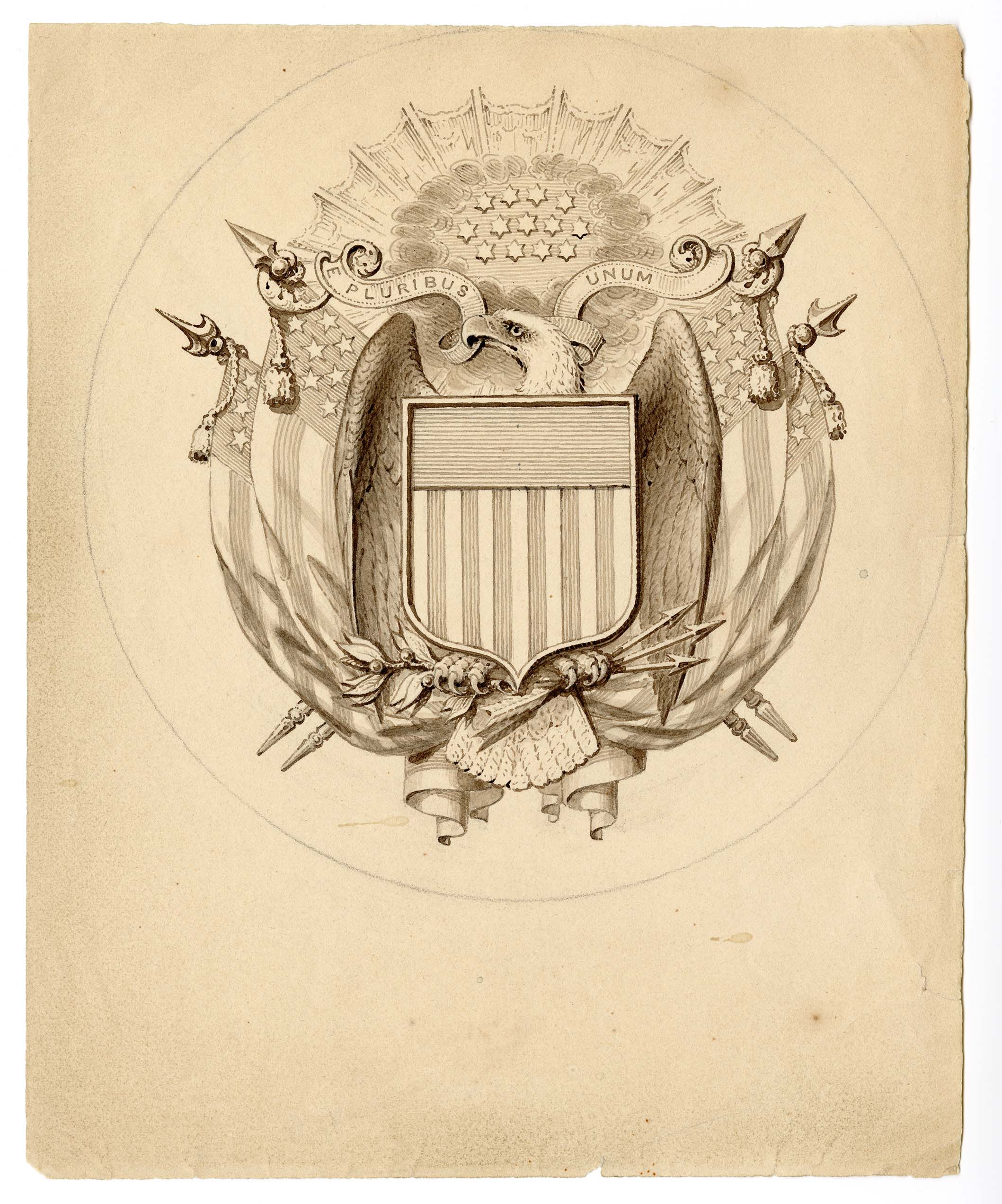

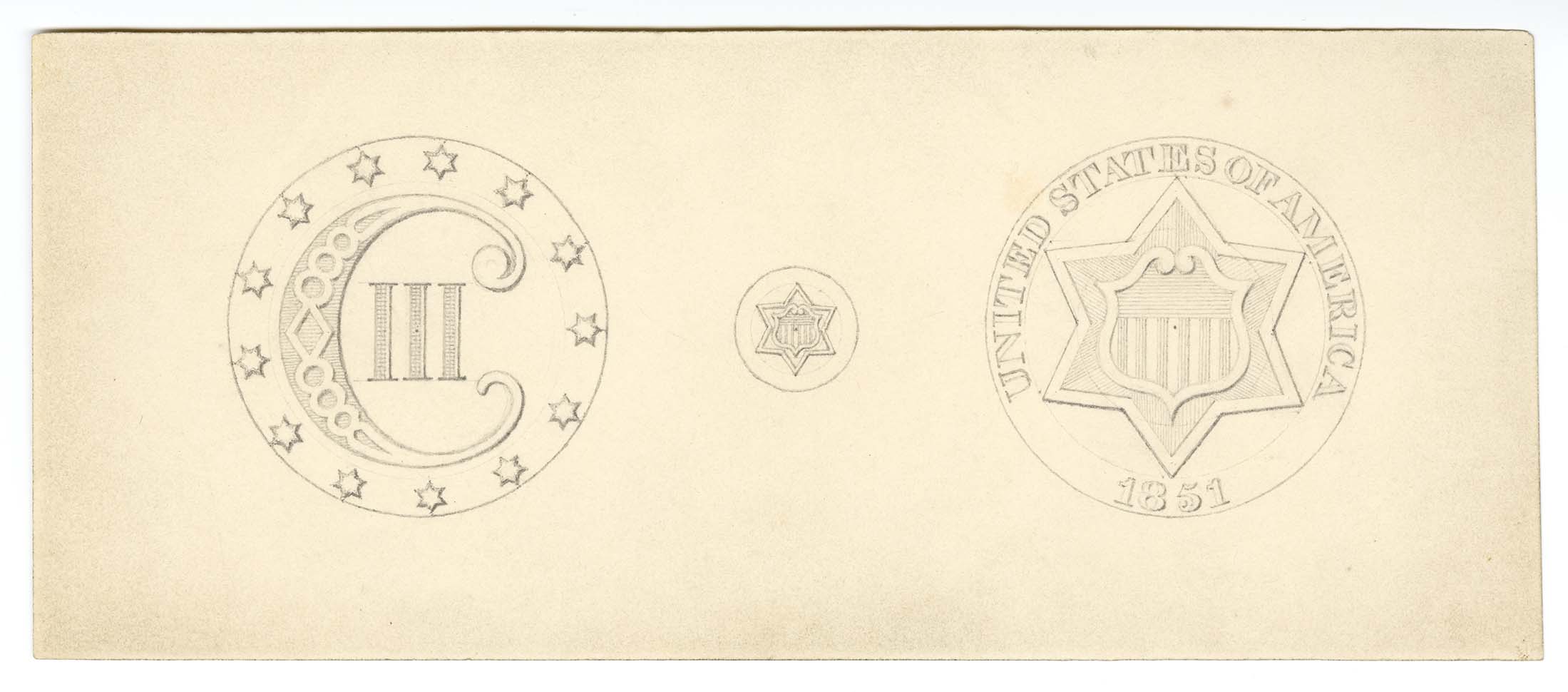

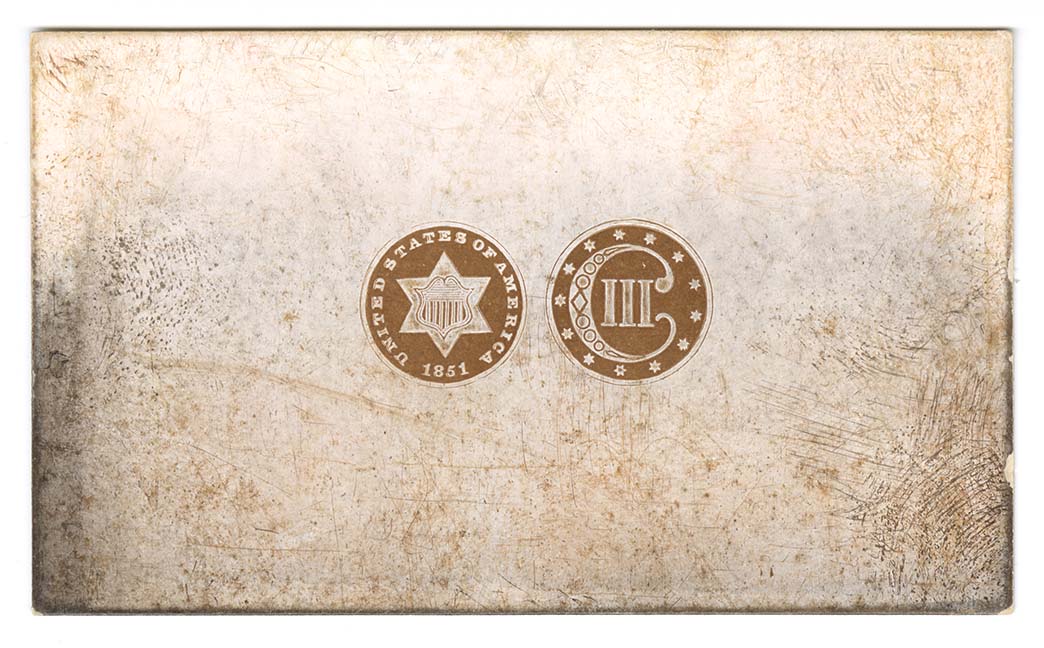

The Franklin Peale Controversy and Coins of Contention

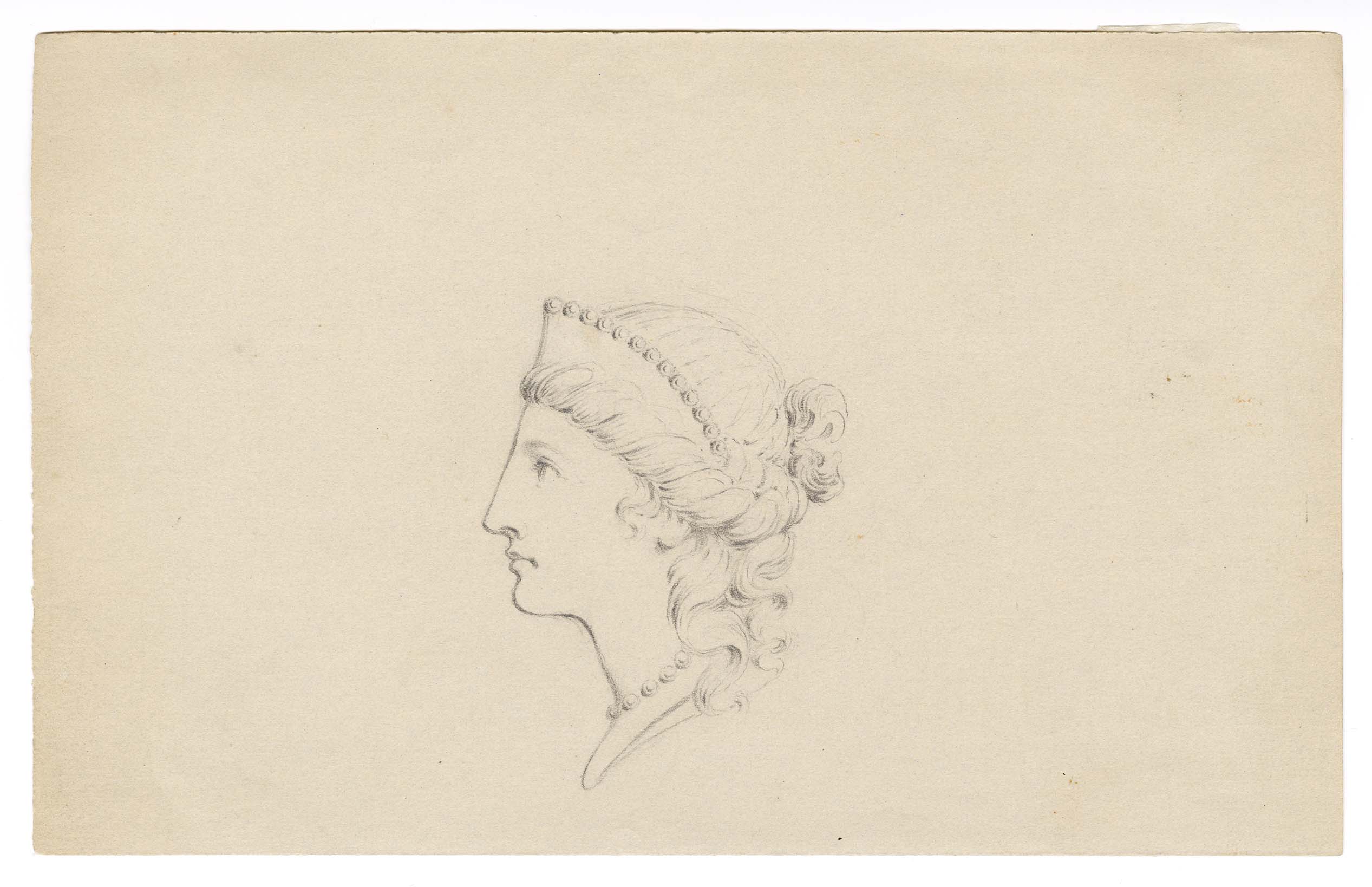

Longacre was appointed Chief Engraver of the United States Mint in 1844. Although he was a successful engraver, he lacked any experience in the art of engraving on dies. The Director of the United States Mint, Robert Maskell Patterson (1787-1854), and the Chief Coiner, Franklin Peale (1795-1870), were critical of Longacre’s inexperience. They also perceived his presence as a threat to their private business which utilized Mint resources and machinery. These two factors would cause clashes at the Mint between these men. Subsequently, Longacre’s coin designs were under constant scrutiny as long as Patterson and Peale worked at the Mint.