|

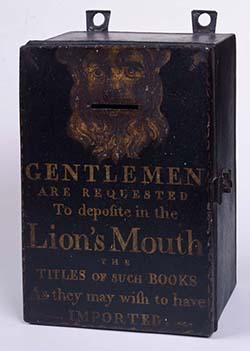

Lion’s Mouth Suggestion Box (American, ca. 1750). Meant to be hung on the wall, this suggestion box solicited members to submit their recommendations for books the Library Company should acquire. Founded by Benjamin Franklin and like-minded aspiring artisans and tradesmen who hoped to improve themselves, the Library Company’s collection reflected their needs and wants, including a large number of architectural and design books. [Catalog Record] |

|

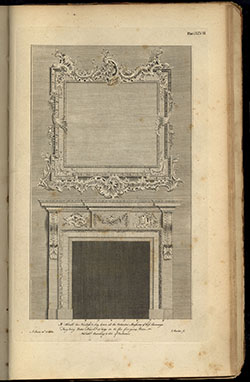

Abraham Swan, The British Architect: or, The Builder’s Treasury of Stair-Cases (London, 1758). The Library Company, by the time of the Revolution, owned the largest collection of architectural books in the colonies. Valued and popular, these design books and manuals provided instructions and models. Swan’s book with sixty plates furnished designs of various orders, patterns for ornamental work, and practical directions for building roofs and staircases. It helped popularize the Rococo in America. |

|

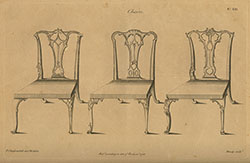

Thomas Chippendale, The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (London, 1755). Reproduction. Born 300 years ago, Thomas Chippendale’s (1718-1779) name is synonymous with style. |

|

Thomas Chippendale, The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (London, 1755). The ranks of the Library Company’s members included a number of prominent cabinetmakers: Benjamin Randolph, William Savery, and James Gillingham to name a few. They had access to Chippendale’s Director, which the Library Company acquired sometime between 1764 and 1769. Philadelphia cabinetmakers embraced the Chippendale or Rococo style and created sophisticated pieces that testify to their skill and artistry. |

|

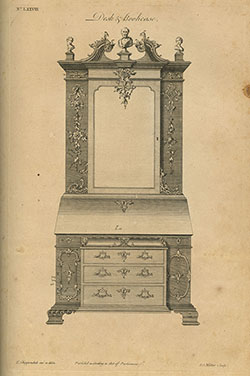

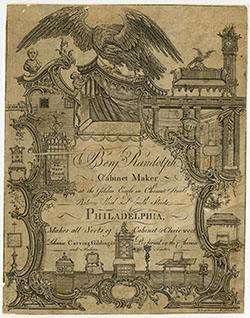

James Smither, engraver, Benjn. Randolph Cabinet Maker, at the Golden Eagle in Chesnut Street (Philadelphia, 1769). Copperplate engraving. Benjamin Randolph (1721-1791), a prominent and successful cabinetmaker, produced elegant, Chippendale-style furniture in Philadelphia. He became a Library Company member in 1766. This engraved advertisement celebrated the substantial house and shop he built on Chestnut Street in 1769. The influence of Thomas Chip-pendale’s Director, a copy of which was in the Library, can clearly be seen in his tradecard. Notice the similarities of the secretary bookcase at the bottom and the bust at the top left. [Catalog Record] |

Reading and Writing Stand (Philadelphia, ca. 1770s). Gift of Albanus C. Logan, 1870. Owned by John Dickinson. This delightful four-sided, mahogany reading and writing desk, provides multiple surfaces for books and papers. To function as a standing desk, it can be raised or lowered by turning along the pole. A locked compartment allows for storing correspondence or other valuables. Slots on each side pull out that can hold an inkwell. Founding father, John Dickinson (1732-1808), known as the “Penman of the Revolution” for his numerous publications supporting the American cause, owned this desk, and his great-grandson gave it to the Library Company. Notice the Chippendale- style carved cabriole legs that end in ball-and-claw feet and the carved finial at the top. [Catalog Record] |

|

|

London Society of Cabinet Makers, The Cabinet-Makers’ London Book of Prices and Designs of Cabinet Work, (London, 1793). Prices for over two hundred designs of furniture are listed in this London edition. Only the most ornate pieces were illustrated as the “more common work” could be made “without the assistance of a drawing.” Of twenty-nine total plates, six were signed by the renowned George Hepplewhite (1727-1786), including the “serpentine cabinet” shown here. Elegant and graceful, his designs reflected classical motifs and decorations, such as the urns, inlay, and paintings seen in this example. |

Thomas Sheraton, The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (London, 1793). Cabinetmaker Thomas Sheraton (1751-1806) created one of the most significant pattern books. Inspired by classical design, the furniture has a geometric look with slender lines and a lighter and more delicate overall appearance. In America, this style, known as Federal, became aligned with the spirit of the new Republic. Though clearly influential in Philadelphia, the book did not enter the Library Company’s collection until the 20th century. |