A Fancy Soldier

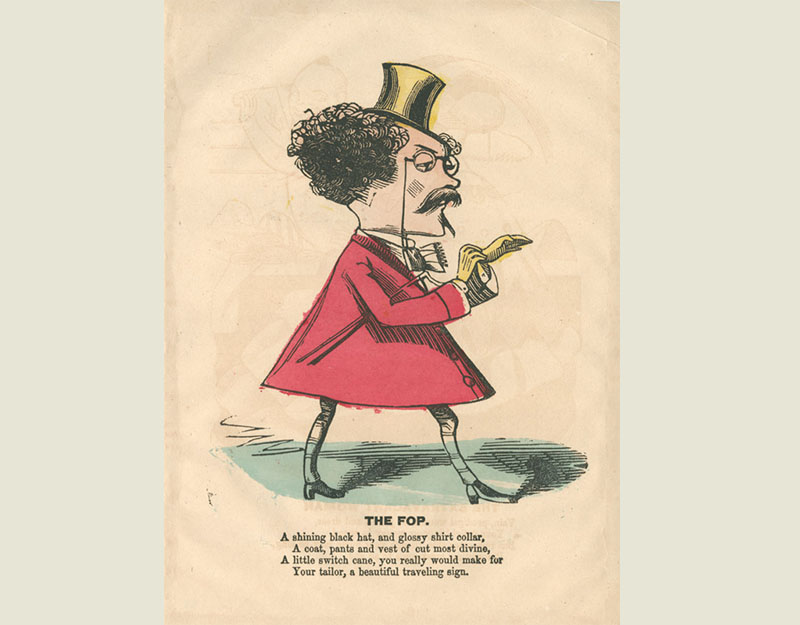

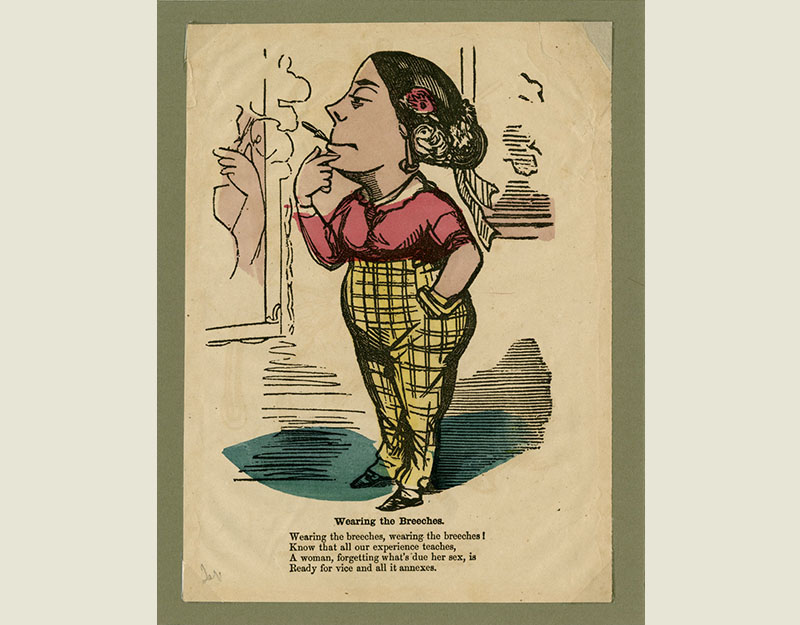

Comic Valentines from the McAllister Collection

In the 19th and early-20th century, comic valentines provided a not-so-subtle way to ridicule people for their personal traits and behaviors. Sent anonymously, many of these caricatures and the accompanying verses poke fun of people's failure to conform to gender norms. For men, comic valentines equate long hair, vanity, and unwillingness to serve in the military with effeminacy. Such men were often labeled "fops" or "dandies." Similarly, for women, wearing trousers or participating in "masculine" activities could lead to being labeled "tomboys." The verse often suggests that an effeminate man or a masculine-seeming woman (or a woman who is involved in the suffrage movement) will fail to attract a mate of the opposite sex. Meant to be offensive, such suggestions may have missed the mark entirely for some of the recipients.

Cushmania

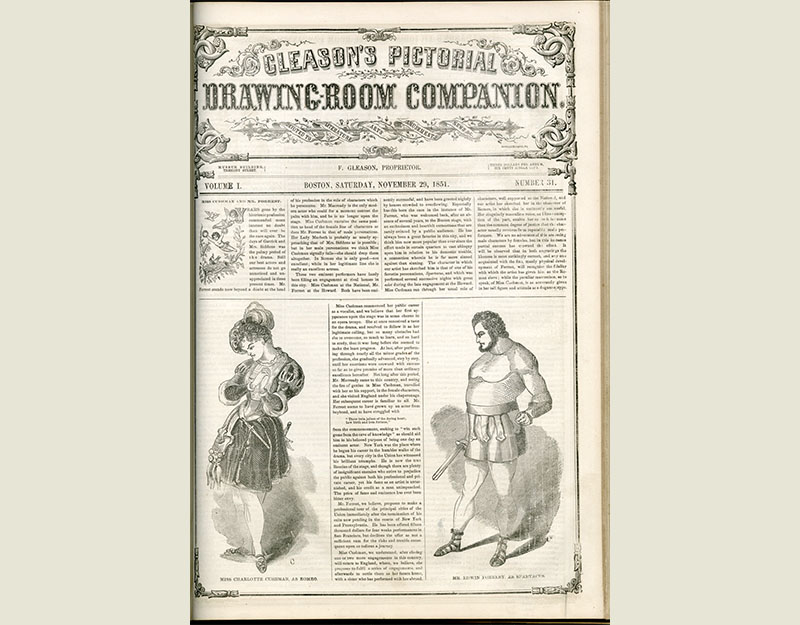

"Miss Cushman and Mr. Forrest," in Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion (November 29, 1851).

According to this article, "[Charlotte Cushman's] singularly masculine voice, and fine conception of the part [of Romeo], enable her to do it far more than the common degree of justice that the character usually receives from reputable male performers. We are no advocates of this assuming male characters by females, but in this instance partial success has crowned the effort."

The juxtaposition of American actress Cushman with the actor Edwin Forrest – the epitome of 19th-century manliness – is striking.

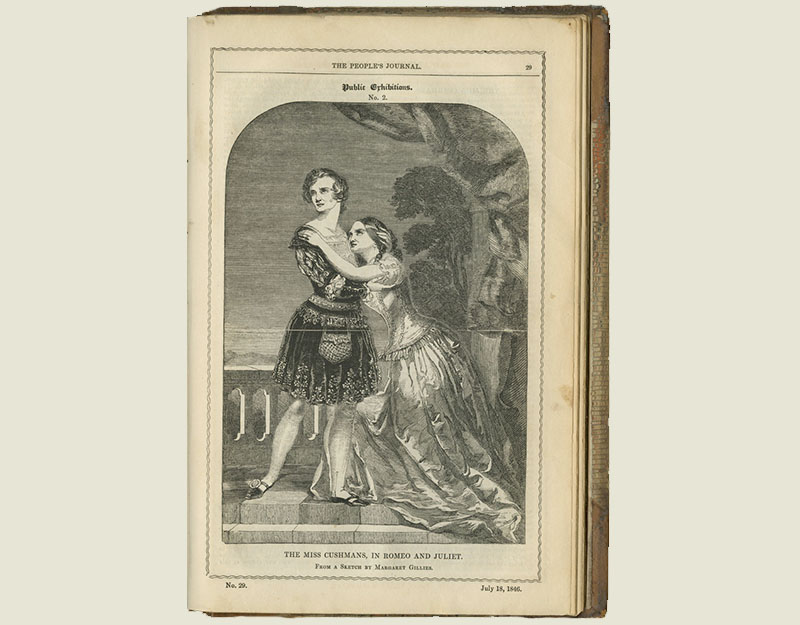

"The Miss Cushmans, in Romeo and Juliet," in The People's Journal (July 18, 1846).

In the 19th century, actresses often performed in male roles. Women on stage in "breeches" roles could seem titillating because men almost never saw women's legs, except in privacy of the boudoir. In her career, Charlotte Cushman (1816-1876) appeared in nearly 190 roles. One of her signature roles was that of Romeo in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. Starting in December 1845, she and her sister Susan appeared in the title roles on the London stage.

Perhaps to offset any appearance of impropriety, Cushman encouraged the idea that she took the role to aid her sister in the aftermath of a failed marriage. But such caution proved unnecessary when critics judged her performance superior to others at the time. English theatergoers caught "Cushmania" as well. To the British, Cushman's "independence" was an American trait.

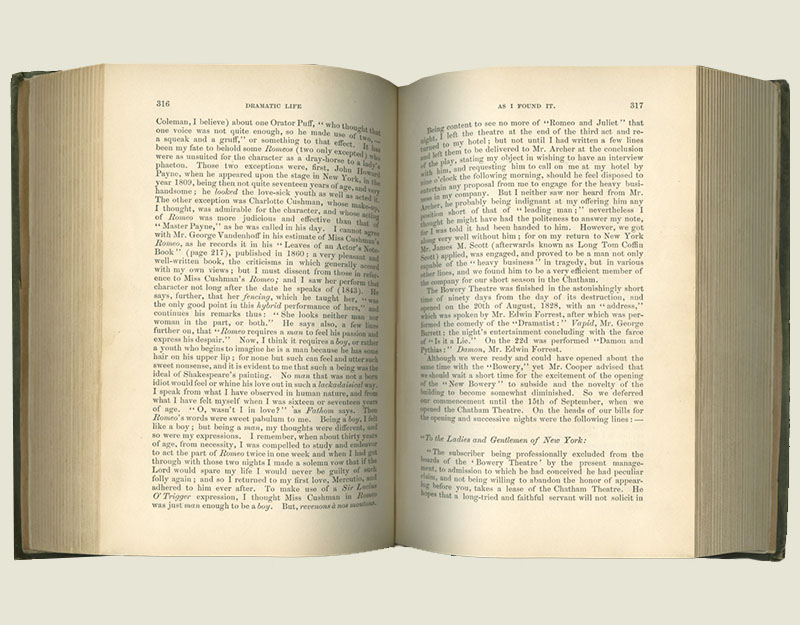

Noah M. Ludlow. Dramatic Life As I Found It. St. Louis: G. I. Jones and Company, 1880.

Charlotte Cushman had played the part of Shakespeare's Romeo as early as 1837 in Albany, New York. American actor and theater manager Noah Ludlow (1795-1886), in his 1880 book Dramatic Life As I Found It, mentions seeing her in the role in 1843. Analyzing the casting of Cushman in the part, he concludes, "Miss Cushman in Romeo was just man enough to be a boy." After all, he writes, "No man that was not a born idiot would feel or whine his love out in such a lackadaisical way."

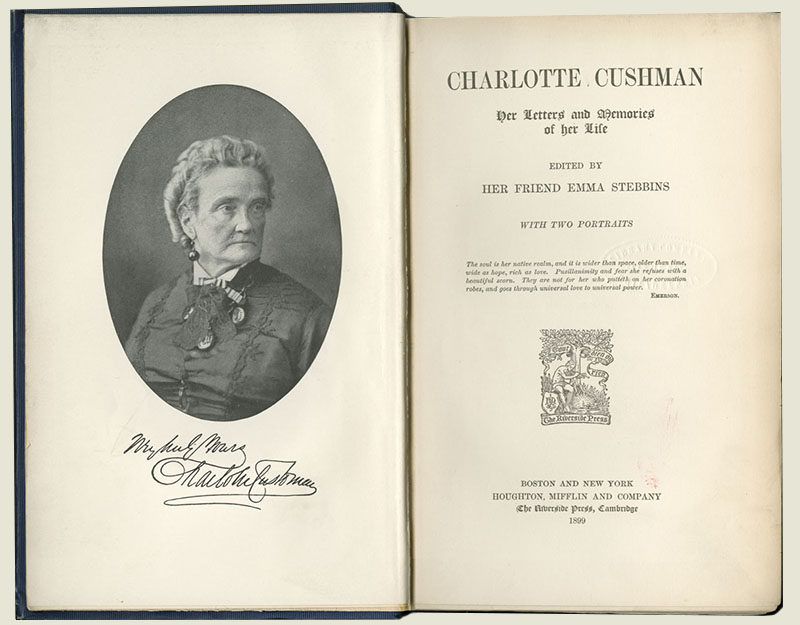

Charlotte Cushman: Her Letters and Memories of Her Life. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Co., 1899.

In 1852, at the age of thirty-six, Cushman had accumulated sufficient wealth to retire from acting, although she returned to the stage on numerous occasions to raise additional funds. In retirement, she maintained a house in London and wintered in Rome. The lively expatriate community in Rome included prominent English and American writers and artists. Possibly through Harriet Hosmer, Cushman met another American sculptor working in Rome – Emma Stebbins (1815-1882), who sculpted a bust of Cushman in 1860. After Cushman's death from breast cancer in 1876, Stebbins produced a memorial volume which went through multiple editions. Stebbins also destroyed quantities of correspondence of a personal nature, keeping what seems to have been a romantic relationship hidden to posterity. However, the culture in which Cushmania had flourished in the 1840s no longer existed. By the 1890s, the phenomenon of actresses in "breeches" parts had become politicized, as evidenced by an article on "The Actress As Usurper of Man's Prerogative," which appeared in the London periodical the Gentleman's Magazine in 1896.