James Reid Lambdin, Benjamin Franklin, [detail], oil on canvas, ca. 1880, after the original by David Martin, 1766.

Section 4: Benjamin Franklin Book Publisher

A publisher is any person who decides that a book is likely to be profitable, finances its printing, distributes it, and takes the risk of a loss if it does not sell, or the profit if it does. Franklin published newspapers, almanacs, and pamphlets at his own risk quite often, but only rarely did he publish a book, because of the greater investment in paper and binding that books entailed. From 1728 to 1748, Franklin printed just sixteen books at his own risk and expense that we know were issued bound. (Coincidentally this is the same number of bound books he printed on commission – see case three.) This was more than any other printer of his time, but still it comes out to less than one a year. Most of the books Franklin published at his own risk were reprints of small inexpensive books, previously published in Britain, whose popularity was already proven.

1731, before the Great Awakening:

I have known a very numerous impression of Robin Hood’s Songs [a popular chapbook] to go off in this Province at 2s. per Book, in less than a twelvemonth; when a small Quantity of David’s Psalms (an excellent Version) have lain on my Hands above twice the Time.Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography

1740, after Whitefield’s evangelical visit:

It was wonderful to see the Change soon made in the Manners of our Inhabitants; from being thoughtless or indifferent about Religion, it seem’d as if all the World were growing Religious; so that one could not walk thro’ the Town in the Evening without Hearing Psalms sung in different Families of every Street.Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography

![Isaac Watts, The Psalms of David, Imitated, seventh edition (Philadelphia: B. F[ranklin] and H. M[eredith] for Thomas Godfrey, 1729). Historical Society of Pennsylvania.](images/thumbs/th4.1.jpg) Isaac Watts, The Psalms of David, Imitated, seventh edition (Philadelphia: B. F[ranklin] and H. M[eredith] for Thomas Godfrey, 1729). Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Isaac Watts, The Psalms of David, Imitated, seventh edition (Philadelphia: B. F[ranklin] and H. M[eredith] for Thomas Godfrey, 1729). Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

The first book Franklin published at his own risk was the first American edition of a new version of the metrical Psalms by Isaac Watts. It was a flop, though it later became hugely popular.

Isaac Watts, The Psalms of David, Imitated, thirteenth edition (Philadelphia: B. Franklin, 1740).

Isaac Watts, The Psalms of David, Imitated, thirteenth edition (Philadelphia: B. Franklin, 1740).

The Great Awakening, the religious revival sparked by the evangelist George Whitefield in 1739, created an unprecedented demand for religious books; this second American edition of Watts’ Psalms was a hit.

![Isaac Watts, Hymns and Spiritual Songs, fifteenth edition (Philadelphia: B. Franklin [and New York: James Parker], 1741).](images/thumbs/th4.3.jpg) Isaac Watts, Hymns and Spiritual Songs, fifteenth edition (Philadelphia: B. Franklin [and New York: James Parker], 1741).

Isaac Watts, Hymns and Spiritual Songs, fifteenth edition (Philadelphia: B. Franklin [and New York: James Parker], 1741).

This edition was printed partly by Franklin and partly by his partner in New York, James Parker; much of the edition was then sent to Boston to be bound. This is the first book whose manufacture was divided among the three major colonial towns.

George Whitefield, A Journal of a Voyage from Gibraltar to Georgia (Philadelphia: B. Franklin, 1739), vol. 1. Historical Society of Pennsylvania; and A Continuation of the Reverend Mr. Whitefield’s Journal (Philadelphia: B. Franklin, 1740), vol. 2. (left image)

Among the largest books Franklin ever published at his own risk, these four volumes each would fit into the palm of your hand (right image). And because there were more subscribers than copies printed, the risk he ran was nil.

Samuel Richardson, Pamela: or, Virtue Rewarded, fifth edition, two vols. (London, Printed; Philadelphia, Reprinted, and sold by B. Franklin, 1742-43). Photograph courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

Samuel Richardson, Pamela: or, Virtue Rewarded, fifth edition, two vols. (London, Printed; Philadelphia, Reprinted, and sold by B. Franklin, 1742-43). Photograph courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

This was the first novel published in America, and a best seller in England, but Franklin’s reprint was a disappointing venture. Novels were too much subject to the whims of fashion. Not until 1768 was another one published in America.

![M. T. Cicero, Cato Major, Or His Discourse of Old-Age: With Explanatory Notes [translated by James Logan] (Philadelphia: Printed and sold by B. Franklin, 1744).](images/thumbs/th4.6.jpg) M. T. Cicero, Cato Major, Or His Discourse of Old-Age: With Explanatory Notes [translated by James Logan] (Philadelphia: Printed and sold by B. Franklin, 1744).

M. T. Cicero, Cato Major, Or His Discourse of Old-Age: With Explanatory Notes [translated by James Logan] (Philadelphia: Printed and sold by B. Franklin, 1744).

All the books Franklin published were reprints of English works except this translation of Cicero by James Logan. He printed it in large type with red ink on the title page on creamy white imported Genoese paper to flatter the powerful Logan and to make it easy for him to read it, since he was nearly blind.

M.T. Cicero, Cato Major. . . With Explanatory Notes by Benj. Franklin, LL.D. (London: Printed for Fielding and Walker, 1778).

M.T. Cicero, Cato Major. . . With Explanatory Notes by Benj. Franklin, LL.D. (London: Printed for Fielding and Walker, 1778).

This later London reprint of Cato Major marks Franklin’s transformation from printer and publisher into author. Here both Franklin the publisher and Logan the translator have disappeared, while Franklin is now wrongly claimed to have been the author, and his fame as an author is confirmed by the portrait frontispiece.

{The New Testament (London: T. Baskett, Printer to the King’s most excellent majesty [i.e., Philadelphia: B. Franklin], 1745)}. No copy known.

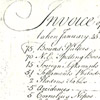

Franklin and Hall, Inventory of book stock (Philadelphia, 1748). Reproduction courtesy of the American Philosophical Society.

The Bible was the largest selling book in colonial America, but it was reserved to the King’s printer by a royal patent. Supposedly. We know Franklin printed the New Testament from a 1748 inventory of his stock where he noted “51 Testaments Philadelphia Printing.” No copy of this Testament is known, but one may yet turn up, since he probably used a false London imprint so it might escape notice both then and today.

The Bible was the largest selling book in colonial America, but it was reserved to the King’s printer by a royal patent. Supposedly. We know Franklin printed the New Testament from a 1748 inventory of his stock where he noted “51 Testaments Philadelphia Printing.” No copy of this Testament is known, but one may yet turn up, since he probably used a false London imprint so it might escape notice both then and today.