Peter Cooper, The South East Prospect of the City of Philadelphia [detail], oil on canvas, ca. 1718. Click here for complete image.

Section 1: The Printer as Writer

In colonial America, printers often needed to be writers. Franklin began his career as a writer when he was apprenticed to his brother, James Franklin, for whom he wrote his first published work: “grubstreet” ballads. Having got a taste for writing, Franklin went on to submit articles to his brother’s newspaper under the pseudonym of a widow, Silence Dogood. Pseudonymity concealed his identity – in this case from his own brother -- and it also enabled him to experiment with the multiple identities that could be constructed through fictional voices.

Franklin had a lifelong fascination with the relation between printing, writing, and revision. The epitaph he wrote for himself imagines his resurrected body as a revised edition, and he sees his Autobiography as an opportunity to correct the “errata” of his youth. The Autobiography was composed with half of each page blank for revisions and corrections, and his famous act of self-revision, his “table of virtues,” was on an ivory memorandum-book so his writing could be easily wiped off with a wet sponge.

Franklin learned to be a writer by laboriously copying and recopying articles in The Spectator and other models. Against emergent notions of “genius,” Franklin stressed “ingenuity,” which included the ability to learn from others. Against notions of intellectual property, he emphasized the free circulation of knowledge, as when he refused to patent his Franklin stove.

I now took a Fancy to Poetry, and made some little Pieces. My Brother, thinking it might turn to account encourag’d me, and put me on composing two occasional Ballads… They were wretched Stuff, in the Grubstreet Ballad Style, and when they were printed he sent me about the Town to sell them.

[B]eing still a Boy, and suspecting that my Brother would object to printing any Thing of mine in his Paper if he knew it to be mine, I contriv’d to disguise my Hand, and writing an anonymous Paper I put it in at Night under the Door of the Printing-House. It was found in the Morning and communicated to his Writing Friends when they call’d in as usual. They read it, commented on it in my Hearing, and I had the exquisite Pleasure, of finding it met with their Approbation, and that in their different Guesses at the Author none were named but Men of some Character among us for Learning and Ingenuity.Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography

The New-England Courant 1721–1726, Published by James and Benjamin Franklin (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1924–1925). Facsimile.

The New-England Courant 1721–1726, Published by James and Benjamin Franklin (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1924–1925). Facsimile.

Franklin’s earliest surviving writing was a series of satirical essays published while he was still an apprentice in his older brother’s newspaper, The New England Courant, under the pseudonym “Silence Dogood.” Franklin’s own file of the paper is now in the British Library; in it he wrote the authors’ initials beside anonymous articles. His own initials, “B.F.,” here mark the third “Silence Dogood” essay.

Benjamin Franklin, Letters from “Martha Careful” and “Caelia Shortface” to The American Weekly Mercury (Philadelphia: Andrew Bradford, January 21, 1729).

Benjamin Franklin, Letters from “Martha Careful” and “Caelia Shortface” to The American Weekly Mercury (Philadelphia: Andrew Bradford, January 21, 1729).

His first appearance in print in Philadelphia was this pair of letters from “Martha Careful” and “Caelia Shortface” in Andrew Bradford’s newspaper. They made fun of Franklin’s competitor and former employer Samuel Keimer, whose newspaper was publishing articles from an encyclopedia in alphabetical order, including one on “Abortion.”

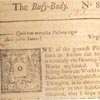

Benjamin Franklin, “The Busy-Body,” No. 8 in The American Weekly Mercury (Philadelphia: Andrew Bradford, March 20–27, 1729).

Benjamin Franklin, “The Busy-Body,” No. 8 in The American Weekly Mercury (Philadelphia: Andrew Bradford, March 20–27, 1729).

With the help of his friend Joseph Breintnall, Franklin continued the attack on Keimer in a series of essays under the pseudonym “Busy Body.” In his file of The American Weekly Mercury, given to the Library Company by Breintnall, Franklin kept track of what he and Breintnall wrote with the initials “B.F.” and “J.B.” The essays helped drive Keimer out of business.

Benjamin Franklin, Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Benjamin Franklin (London: Printed for Henry Colburn, British and Foreign Public Library, 1818), vol. 1.

Benjamin Franklin, Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Benjamin Franklin (London: Printed for Henry Colburn, British and Foreign Public Library, 1818), vol. 1.

Franklin’s famous diagram of his method for recording faults was first written in a paper notebook, but it wore out with constant erasure, so he copied the diagram in red ink on ivory tablets, from which pencil marks were easily erased. His grandson inherited both the paper and the ivory notebooks, now lost, and published the diagram in 1818.

Ivory memorandum book, probably nineteenth century, with the days of the week stamped on six of the leaves. Private collection.

Ivory memorandum book, probably nineteenth century, with the days of the week stamped on six of the leaves. Private collection.

Like most ivory notebooks, this is made like a fan. Franklin both sold such notebooks and transferred his table of virtues onto one.

John Goldsmith, An Almanack for the Year of Our Lord God M.DCC.LXIX (London: Richard Hett, for the Company of Stationers, [1768]). Private collection.

John Goldsmith, An Almanack for the Year of Our Lord God M.DCC.LXIX (London: Richard Hett, for the Company of Stationers, [1768]). Private collection.

Erasable tablets were widely used in Franklin’s time. Here specially treated erasable paper was bound with an almanac. The silver stylus, which acts as a closing device, has been used for the silverpoint writing.

Nathaniel Ames, An Astronomical Diary; Or, Almanack, for … 1771 (Boston: Printed and sold by the Printers and Booksellers, [1770]).

Nathaniel Ames, An Astronomical Diary; Or, Almanack, for … 1771 (Boston: Printed and sold by the Printers and Booksellers, [1770]).

Franklin’s epitaph for himself, which he wrote when he was 28, circulated widely in his lifetime. The heading here emphasizes the connection between Franklin as writer and printer.

Thomas Jefferson’s Ivory memorandum book in which he took notes that he could later transfer into more permanent notebooks. Reproduced by permission of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

Thomas Jefferson’s Ivory memorandum book in which he took notes that he could later transfer into more permanent notebooks. Reproduced by permission of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

Advertisements for Ivory memorandum books in Titan Leeds, The American Almanack for. . . 1735 (Philadelphia: Andrew Bradford, [1734]) [left image]; Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia: B. Franklin, May 20, 1742).

[right image]

Ivory memorandum books were widely sold in Philadelphia, including by Franklin and his main competitor, Andrew Bradford.

Benjamin Franklin’s epitaph, Manuscript, before 1790. Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Benjamin Franklin’s epitaph, Manuscript, before 1790. Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

This manuscript copy of Franklin’s famous epitaph incorrectly gives Franklin’s birthday as June 6 instead of January 6 (January 17 after the calendar reform of 1752).