Art & Artifacts

Discover the Library Company's Art and Artifact Collection

Death Masks and Life Masks

Mask making is an ancient tradition in most cultures. Death masks are casts taken from a cadaver while life masks are casts taken from a living person. These masks are mostly made from wax or plaster using essentially the same technique. The face and head are oiled or greased, and then thin layers of plaster are applied and built up in layers. To aid in removing the mask, threads are embedded into the plaster so that the threads can be pulled. This cast creates a mold. Wet plaster or wax can then be poured into the mold, creating a positive model.

Death and life masks saw a popular revival in the 19th century. Some of the rise in mask making was due the development of scientific beliefs, such as phrenology, that supposed facial features and proportion could explain personal attributes. Masks were taken from eminent persons, such as monarchs and noted authors. Both the death masks and living impressions would be used as models for future portraits or busts. The practice of making life masks and death masks declined with the advent of photography.

Cast of the death mask of Napoleon.

Plaster.

12 1/2" x 5 3/4" x 6".

Library Company of Philadelphia. Bequest of Anne Hampton Brewster, 1892.

Napoleon’s death mask is the only mask in the collection actually taken post-mortem, and it represents the popularity of the European tradition of taking casts of famous leaders. The mask was taken nearly two days after the former emperor’s death in May of 1821. The slight distortions and inaccuracies characteristic of death masks can be seen that are the result of the weight of the plaster on the face. Dr. Francesco Antommarchi, Napoleon’s personal physician who was present at Napoleon’s death, said that the mask was “correct so far as the shape of the forehead and nose was concerned.” Death masks would occasionally be altered to make the impressions more lifelike, the eyes being stylized as open and the lips closed from being slightly parted in death, although that is not seen here. This mask stands as an example of a death mask in the traditional sense, as an effigy and memento of the deceased.

Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828).

Mask of George Washington, c. 1785-1792.

Plaster.

11" x 9" x 4".

Library Company of Philadelphia. Source unknown.

When the state of Virginia wanted to commission a statue of George Washington, both Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin endorsed French neoclassical sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon. Jefferson even said that, “he is the first statuary of the age.” In 1785, Houdon accompanied Benjamin Franklin to visit Washington at his Mount Vernon home. Houdon spent two weeks at Mount Vernon, sketching, measuring, and observing the General as well as creating this plaster life mask. To make the mask, Houdon had Washington lie down. He coated Washington’s face with grease and covered his eyes before applying the plaster; Washington was able to breathe through two quills in his nostrils. Houdon sculpted Washington’s eyes afterwards. He returned to Paris and used this mask to aid him in sculpting a marble, life-sized sculpture of Washington which still resides in the Richmond Capitol. This mask would be used again for many other sculptures of Washington.

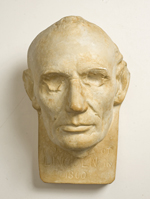

Boston Sculpture Co.

Mask of Lincoln, c. 1880-1920.

Plaster.

12" x 8" x 6".

Library Company of Philadelphia. Gift of Ms. Rose Gallagher, 1990.

This mask is a reproduction of the life mask of Abraham Lincoln made by sculptor Leonard Volk in 1860, shortly before his nomination for President. Here we see a young, beardless Lincoln. Another life mask of Lincoln was created by Clark Mills in 1865. The stress the Civil War had on Lincoln can easily be seen by contrasting the two masks. Though Lincoln was frequently photographed, this mask captures every feature of his countenance.