Art & Artifacts

Discover the Library Company's Art and Artifact Collection

Struck into Metal

Medals recall the people, deeds, and circumstances which have influenced the life of nations. There had long been a tradition of bestowing medals in Europe, and Americans soon realized their value. Indeed, John Adams wrote, “The Utility of Medals has ever been impressed strongly upon my mind.”1 These medals from the Library Company’s collection represent a number of achievements and causes. Be it for publishing, peace, or presidential campaigns, they honor a myriad of successes. These miniature tokens have the power to communicate a great deal, both then and now. Each medal represents an expansive moment of exchange and can offer us glimpses of the people, places, and ideas that were important enough to be cast into metal.

Edward Duffield (1720-1801), engraver; Joseph Richardson (1711-1784), struck by.

Peace Medal (from the Friendly Association for Regaining and Preserving Peace with the Indians), 1757.

Silver.

Library Company of Philadelphia.

Peace Medal

This medal depicts a bust of King George II on one side and, on the reverse, a Quaker holding a peace pipe at a council fire with an Indian. Crafted in 1757, this medal was the first peace medal made in America. It was commissioned and presented by the Friendly Association, a group of Pennsylvania Quakers that attempted to mediate negotiations between Delaware Indians and the Pennsylvania Assembly. Benjamin Franklin and members of the Friendly Association would distribute these medals to Native Americans as tokens of goodwill.

Anti-Slavery Medal, 1838.

Brass.

Library Company of Philadelphia. Gift of Chris McCauley, 1996.

Anti-Slavery Medallion, 1838

A common token in anti-slavery circles, abolitionist women distributed and sold these medals at anti-slavery fairs, using the proceeds to fund their cause. This particular medal, minted in New Jersey in 1838, reads “Am I Not a Woman and a Sister” and depicts an enslaved women kneeling in chains. The slogan, made popular by Philadelphia abolitionist Elizabeth Margaret Chandler, would come to define the abolitionist movement, particularly in female anti-slavery societies. In this version, the “N” in United States is reversed, a tactic engravers used to avoid counterfeiting.

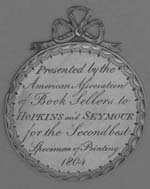

American Association of Booksellers.

Silver Medal, 1804.

Silver.

Library Company of Philadelphia. Purchase of the Library Company with the help of Joseph Felcone, 1997.

Silver Medal Award

This small silver medal reads “Presented by the American Association of Book Sellers to Hopkins and Seymour for the Second Best Specimen of Printing, 1804.” Beginning in 1802, American book fairs were held semi-annually in New York and Philadelphia to honor publishers and to unite the profession. The first place medal was awarded to Robert Carr of Philadelphia, but this runner-up medal went to the New York publishing firm of Hopkins and Seymour for their publication of the History of the Reign of the Emperor Charles V. When Mathew Carey ordered a copy of the book after the duo won the prize, the printer proclaimed that the medal had wrought “magic” upon the edition.

Political campaign medal, Harrison/Tyler, ca. 1840-41.

Brass. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Political campaign medal "Harrison The People's Choice," ca. 1840-41.

Library Company of Philadelphia.

Harrison Campaign Medals

These two political medals are remnants of William Henry Harrison’s presidential campaign of 1840. Because both medals have a small hole in the top, it is likely that they were worn about the neck with a ribbon and used as a campaigning tool. Campaign medals such as these are indicative of Harrison’s groundbreaking approach to politics, as he was the first candidate to stump on his own behalf. Both medals portray the bust of Harrison, a decorated military man, on the front; on the reverse, one depicts a picture of a log cabin with the inscription “The People’s Choice,” while the other shows an eagle framed by the words “Go it Tip” and “Come it Tyler.” “Tip” refers to Harrison’s nickname “Tippecanoe” from the famous battle, and John Tyler was Harrison’s running mate. Their campaign slogan was “Tippecanoe and Tyler, Too.” The medals present us with an early glimpse into the fashioning of a political image and the use of ephemera in presidential campaigns.

|

Moritz Furst (b. 1782). |

Moritz Furst (b. 1782). |

Benjamin Rush Medal

This set of inscribed dies was for a rare medal commemorating Dr. Benjamin Rush, a prominent Philadelphian. One side is a profile of Rush with the inscription “Benjamin Rush MD of Philadelphia,” while the reverse is a lush portrayal of his countryside home “Sydenham,” a name given in honor of the English physician Thomas Sydenham. “Sydenham” floats in the background of the inscription while the motto “Read, Think, Observe” sits in the foreground, a quote from one of Rush’s medical lectures.

[1] John Adams to Nathanael Greene, 9 May 1777, in Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1774-1789, ed. Paul H. Smith et al. (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1976-2000).