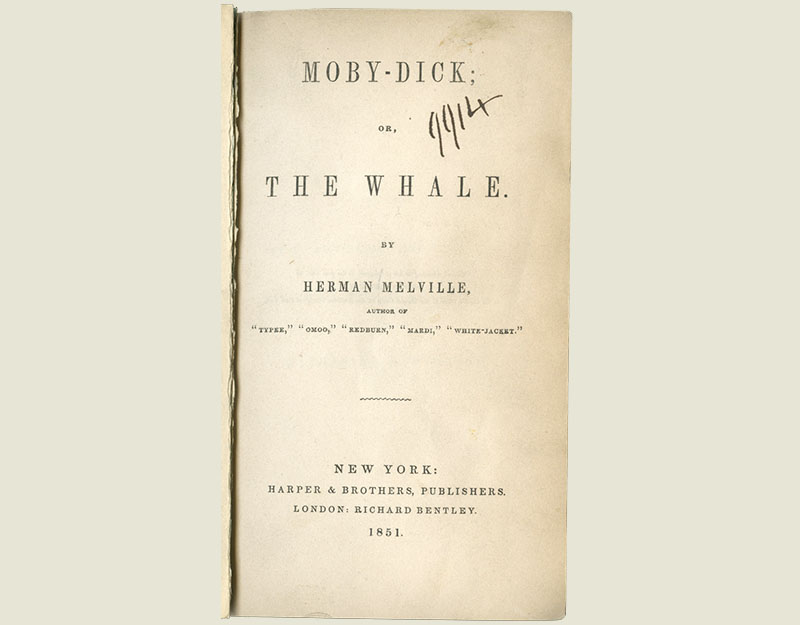

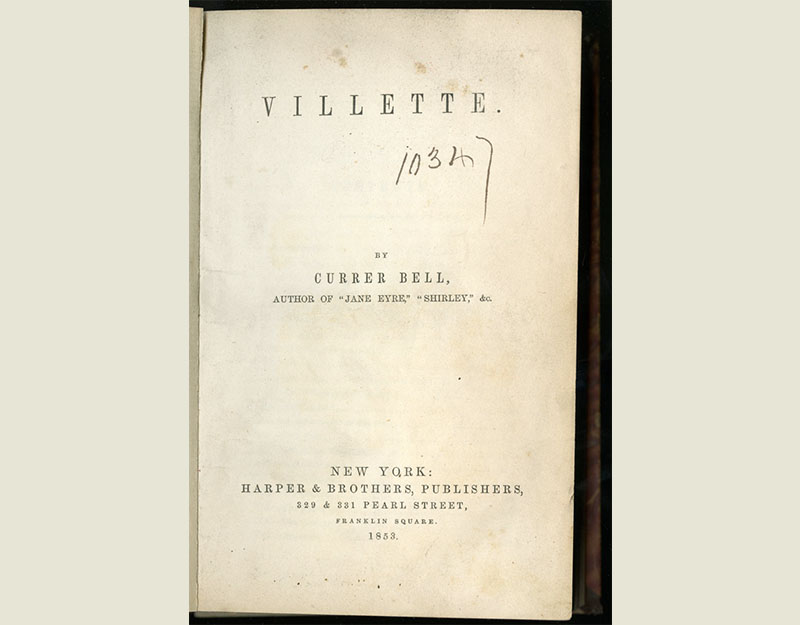

Herman Melville. Moby-Dick, or, The Whale. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1851.

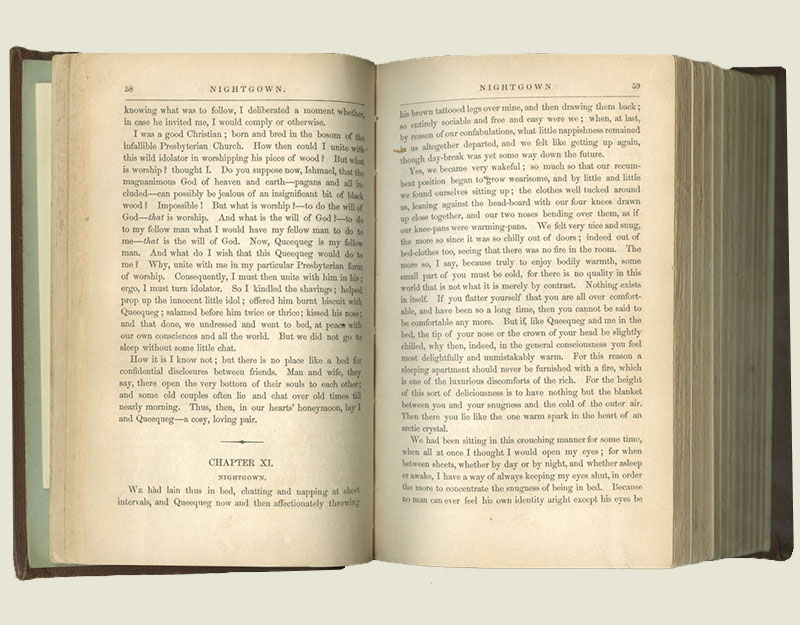

In Moby-Dick, the narrator Ishmael meets the South Pacific islander Queequeg right before they sign on to a whaling voyage. The two become close ("a cosy, loving pair"), despite having been raised in extremely different cultures. Melville used the unusual setting to depict their friendship as a valid alternative to male-female domestic relations.

Fortunately, the Library Company acquired this copy from the first American edition soon after publication. In 1853 a fire at Harpers' destroyed the remaining copies as well as the stereotype plates.