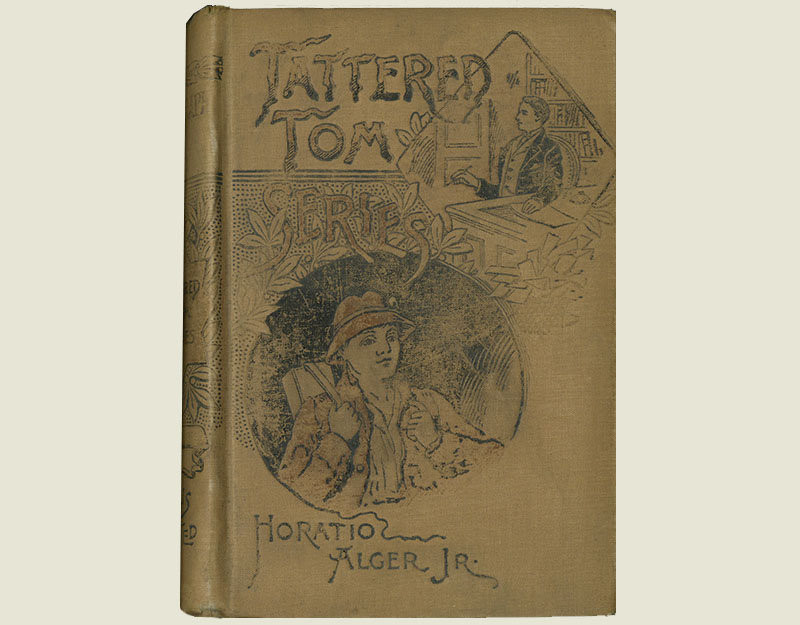

Horatio Alger, Jr. The Telegraph Boy. Philadelphia: Henry T. Coates & Co., [between 1896 and 1904?]. Gift of Renée Betts.

Horatio Alger Jr (1832-1899) was forced to resign as a Unitarian minister due to allegations that he had had sexual relations with boys in his congregation in Brewster, Massachusetts – charges he did not deny. He went on to become a prolific author, selling seventeen million copies of his one hundred books for boys. The most successful was Ragged Dick, or, Street Life in New York with the Boot-Blacks, which first appeared in 1868 and was still in print at the turn of the century. Alger's typical boy hero triumphs over adversity thanks to his own initiative and the help of a benevolent male mentor. The Telegraph Boy, shown here, is the last of four titles in Alger's Tattered Tom series. In the first one, Tattered Tom, or, The Story of a Street Arab, "Tom" is a homeless girl who lives on the streets until she is discovered to be the heir to a fortune. She is depicted on the covers, wearing a hat that helps conceal her gender.

Following Alger's death in 1899, his sister destroyed his personal papers in accordance with his wishes. His 1928 biographer, Herbert R. Mayes, fabricated sources. Mayes's book became the basis for subsequent biographical sketches. Fifty years later, in 1978, Mayes admitted that the work was a hoax, and today few people realize that the stories about street urchins who make their way in the world were written by a man who had "a natural liking for boys," as Alger himself described it. In popular culture, his name has become synonymous with financial achievement of the "rags to riches" sort.