National Lincoln Monument Association. Celebration by the Colored People’s Educational Monument Association in Memory of Abraham Lincoln on the Fourth of July, 1865, in the Presidential Grounds, Washington, DC. Washington, DC: McGill & Witherow, 1865.

Largely organized by Northern African Americans, the Colored People’s Educational Monument Association was established to honor the memory of the late President Lincoln by founding a school for African Americans. This program for an Association event held on White House grounds notes that this was the first time African Americans had occupied this symbolic center of American democracy in the nation’s capital. Although the association had an auspicious beginning, it eventually fell apart due to internal conflicts about fundraising methods.

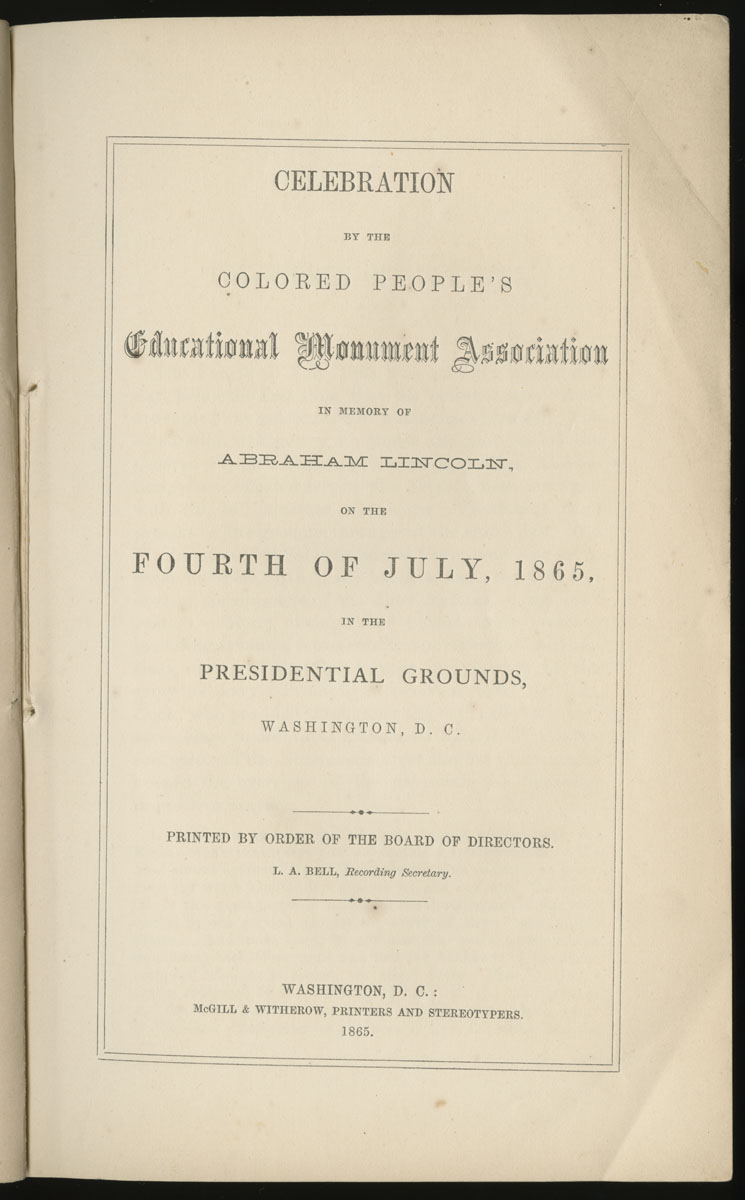

John W. Thompson. An Authentic History of the Douglass Monument. Rochester, NY: Rochester Herald Press, 1903.

The creation of physical monuments in public places was one way for African Americans to inscribe their status as citizens on the Northern landscape. Almost immediately after Frederick Douglass’s death in 1895, African American citizens of Rochester, New York, organized a fund to erect a monument in his honor to inspire love of country and liberty in future black generations. Susan B. Anthony, T. Thomas Fortune, and members of Douglass’s family were among those present at the monument’s commemoration in 1899. Douglass considered Rochester to be “where the best years of my life were spent in the service of our people.”

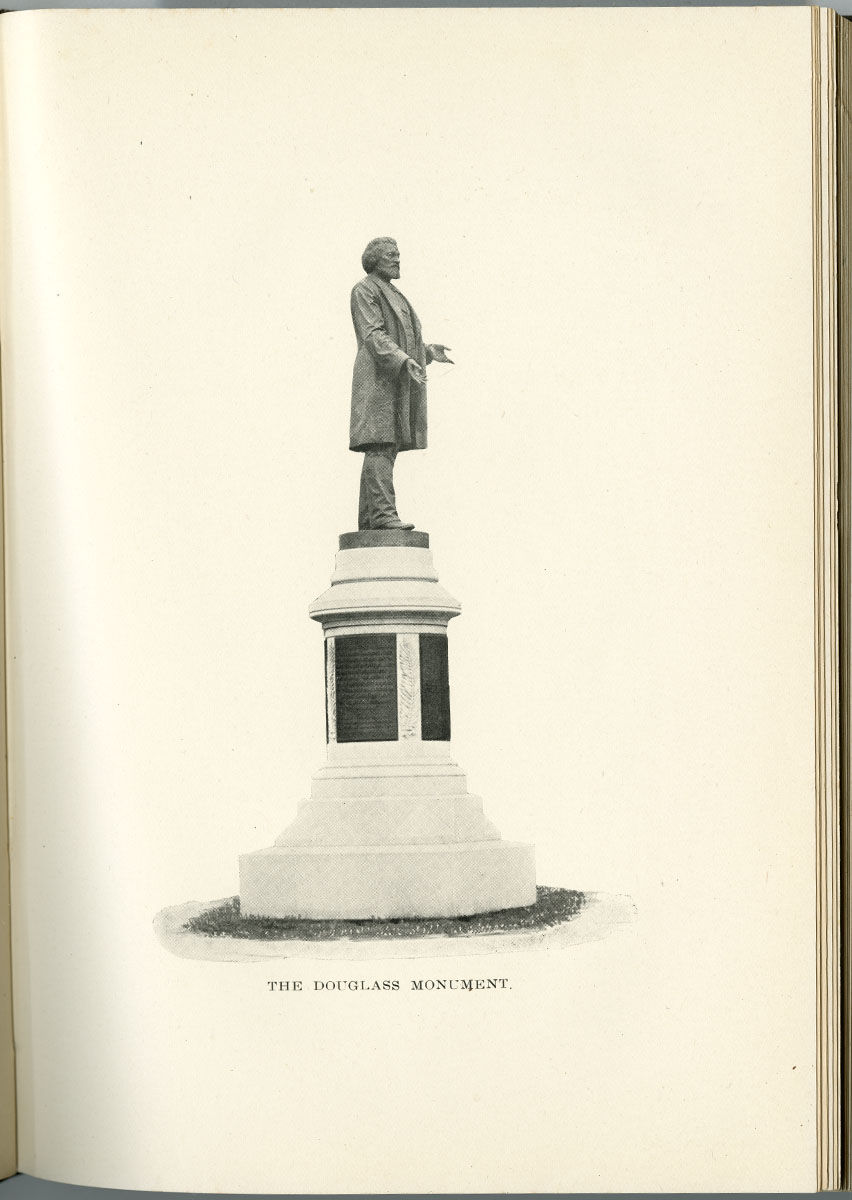

Benjamin Ridgway Evans. First Old Presbyterian Church. 1884.

Founded in 1807, the First African Presbyterian Church was the first such congregation in the United States. The church edifice pictured here was completed in 1811. In the 1890s, the church moved to 17th and Fitzwater Streets to be more convenient to its congregation. Philadelphia antiquarian Ferdinand Dreer commissioned artist Benjamin Ridgway Evans to record unique structures and buildings in Philadelphia that were threatened by destruction due to city’s growth. Among the 152 watercolors that Evans completed were several that offer a glimpse of black street life in the city.

George Bacon Wood. Civil Rights—The Fifteenth Amendment. 1876. Private collection.

This painting by artist George Bacon Wood (1832-1910) illustrates the social implications of the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave black men the right to vote. Set in Philadelphia’s Washington Square, a black man borrows a pipe from a white man in order to light his own. The title contextualizes the significance of the moment, suggesting that the franchise could also lead to social equality between the races. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Washington Square was an important gathering and recreational space for African Americans as they asserted their right to be in the public sphere.

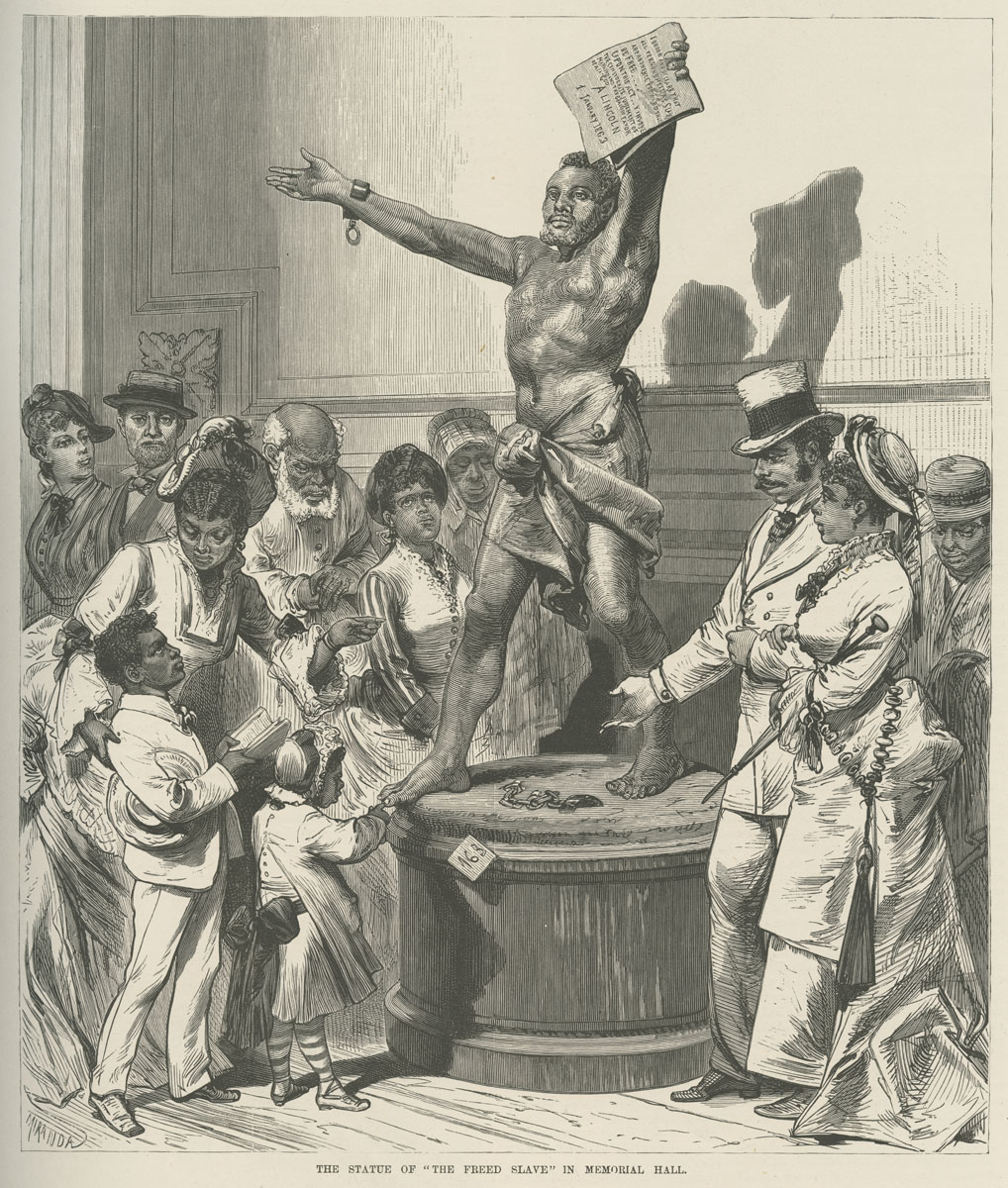

“The Statue of ‘The Freed Slave’ in Memorial Hall” by Fernando Miranda in Illustrated Historical Register of the Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia, 1876 by Frank Henry Norton. New York: American News Co., 1879.

In 1876, Philadelphia hosted the Centennial Exhibition to celebrate the anniversary of the nation’s founding. African Americans were excluded from serving on planning committees, creating displays, and working on fairground construction crews. One of the few representations of African Americans at the fair was the bronze statue The Freed Slave by Austro-Italian sculptor Francesco Pezzicar. In striking distinction to American artwork of the time, the freed slave stands triumphant rather than kneeling submissively in gratitude to white emancipators. While a few visitors were disturbed by the statue’s state of undress, African American visitors of a variety of ages and classes were overwhelmingly drawn to the statue as a symbol of independence and progress since emancipation.

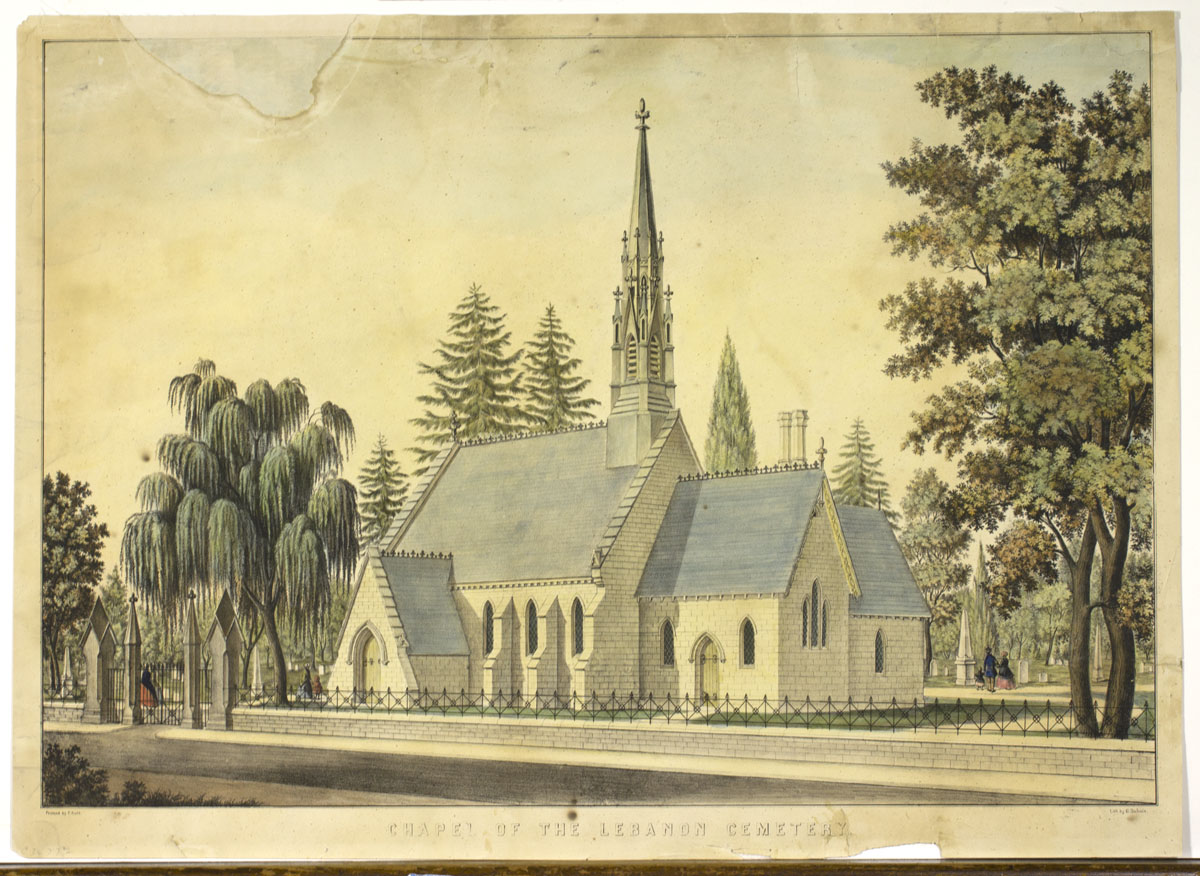

George Dubois. Chapel of the Lebanon Cemetery. Philadelphia: F. Kuhl, ca. 1850. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Owned by Jacob White, Sr., and later by his son, Lebanon Cemetery was one of the city’s few public burial grounds managed by African Americans. Crowds of African Americans annually paraded to Lebanon Cemetery with musical accompaniment down city streets to commemorate the black Union dead on Decoration Day (now Memorial Day).

In 1882, there was a scandal when it came to light that doctors at Jefferson Medical College had been exhuming and stealing bodies for medical research. African American outrage and extensive press coverage led to the arrest and conviction of the parties responsible.

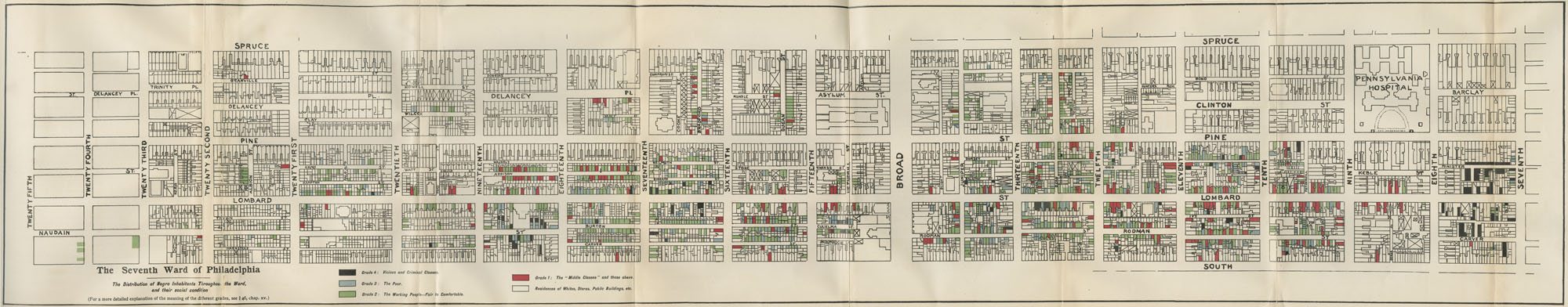

“Map of the Seventh Ward in Philadelphia” in The Philadelphia Negro by W. E. B. Du Bois. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1899.

The Philadelphia Negro, the first sociological study of urban African American life, surveyed the 9,000 residents of the Seventh Ward, which represented the largest concentration of the city’s approximately 45,000 blacks. Although to some observers, the Seventh Ward appeared to be an undifferentiated slum of poverty and crime, the survey revealed the diversity of occupations, family structures, educational attainment, living environments, and income levels among the residents. W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963) hoped that his statistical data would guide public policy and philanthropy to improve the economic and physical condition of black Philadelphians. Although his analysis was sometimes colored by disdain for unrespectable or criminal behavior, he also demonstrated the ways in which racial prejudice stymied African American advancement. Du Bois visited the Library Company of Philadelphia to conduct some of the historical research which contextualized the study.