Essay by Jasmine Nichole Cobb, PhD Duke University

The Colored Beauty. New York: Currier & Ives, 1872.

Images and ephemeral materials that appear in Genius of Freedom reveal that 19-century African Americans placed great value in representation—both cultural and political. Spanning the period from 1830 through 1891, these materials reflect the concerns of free black communities wherein some individuals were privileged with the resources to participate in political organizing but imperiled by the period’s hostility toward African Americans.

Trade card. New York: Sammis & Latham, 1882.

Materials displayed in the Genius exhibition are remarkable for what they convey about the impact of technology on African American culture in the context of slavery. A small cadre of 19th-century African Americans managed to produce their own pamphlets, petitions, and letters despite the fact that slavery suppressed black life and social advancement. Activists and clergypersons, among others, delivered speeches and produced literature that circulated the concerns of the free black community. Free African Americans in Northern states had established communities around their own social, political, and educational institutions. Churches, meeting halls, schools, and the like were places for organizing further political activity and preparing younger generations to continue the fight for emancipation and enfranchisement. The materials in the Genius exhibition tell this story through illustrations of gatherings, public celebrations, images of political leaders, and the depiction of print culture.

By 1830, there were several newspapers that focused specifically on African American and abolitionist audiences. Messages about legal statutes and news about abolition throughout the US and Caribbean broadcast to large audiences across the country. Images such as “The Statue of ‘The Freed Slave’ in Memorial Hall” by engraver Fernando Miranda from the Illustrated Historical Register of the Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia speak directly to the connections between emancipation and 19-century print culture. The illustration comments on Philadelphia’s Centennial Exhibition in 1876, which celebrated the nation’s founding but excluded African Americans from serving on planning committees, creating displays, and working on fairground construction crews. That the “freed slave” on display in the illustration holds Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in one hand and extends the other to reveal an unlocked shackle forges a connection between emancipation, black freedom and literacy.

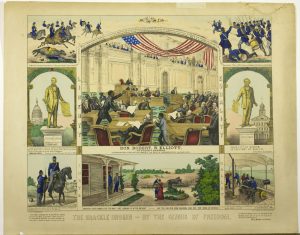

With the help of improved printing technologies—processes that produced brighter colors on paper and uniformity in texts across multiple copies—free African Americans enjoyed better print materials just as whites. Items in the Genius exhibition suggest that African Americans filled their homes with quality images and texts; improvements in communication had an impact in the private space of the home as well as the public spaces of national discourse. One important instance of this shift was to celebrate important men in the African American community. Images such as “Heroes of the Colored Race” and “Distinguished Colored Men” demonstrate how important it was to champion black male leaders. Each print features Douglass in the center. Leaders, including the Rev. Richard Allen and Henry Highland Garnet, orbit around Douglass in the “Distinguished Colored Men” print. The lower corners of the image are flanked with scenes of black life—people rejoicing in front of a home, harvesting produce in front of another house, along with a flower and cornstalks filling out the blank spaces. Together, these items cover the page with symbols that indicate domesticity and rootedness, showing African Americans with claims to the US as home with the support of important political leaders.

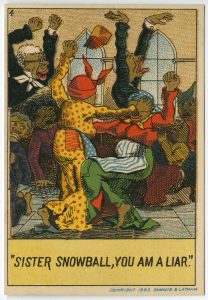

“The National Colored Convention in Session at Washington, DC.” Harper’s Weekly (February 6, 1869).

While public discourse celebrated the triumphs and efforts of a mixed-race antislavery movement, these illustrated materials show that Frederick Douglass and other black male leaders held a uniquely important place in black homes and the political imaginations of African Americans. Douglass is central to the progress of African Americans according to “Heroes of the Colored Race,” supported by U. S. Senator Blanche Kelso Bruce of Mississippi and U. S. Senator Hiram Revels of Mississippi. Lithographer Joseph Hoover created such images for African American households, specifically, and featured scenes of black life in addition to heroes like John Brown. The background vignettes of the illustration tell a story of the transition from slavery to freedom, showing unfree blacks as dignified even in picking cotton, as well as fighting in the civil war; finally, free blacks administer their own education in all black schools and end with freedom and abundance, indicated with an overflowing cornucopia.

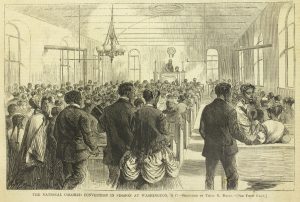

James C. Beard. The Fifteenth Amendment. Celebrated May 19th 1870. New York: Thomas Kelly, 1870.

These images reflect a popular interest in governance as the tool that supports the progressive scenes of black life in the background. Items such as the “Colored Convention” represent the many meetings “convening on a national level to discuss methods for improving” the lives of African Americans, including “their political, economic, and social status in the United States” (Appiah). Political organizing was essential to African Americans in the early 19th century, and

appears in writings and illustrations of the period. Items such as The Fifteenth Amendment show the full narrative of African American activism and culminating celebrations throughout the country that recognized the specifically legislative victories for people of African descent. The image shows that the Fifteenth Amendment, which prohibited the government from barring male citizens the right to vote, also connected to self-sufficiency, marriage, religion and fraternity through images of African Americans engaged in all of the activities. As Genius of Freedom reveals, “African Americans [fought] to repeal discriminatory laws and to elect officials who would protect them from state and extralegal violence” (Appiah), and marked each victory with a public display. Throughout the 19th century, African Americans commemorated legal victories with festivities that openly intertwined the cultural and the political.

The Shackle Broken–By the Genius of Freedom. Baltimore: E. Saches & Co., 1874.

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, and for decades after, US Americans contemplated the impact of black emancipation on public space. Whereas these images were enjoyed in parlors, they also helped to decorate private space with images about public space. African Americans demonstrate a commitment to viewing their own likeness and decorating their homes with black images. The story told by the images in Genius of Freedom tell us that elite African Americans promoted male political leaders, focused their organizing efforts on politics, and voiced their concerns in public spaces.