Debates in the Eighty-Ninth General Assembly of the State of New Jersey on the Bill to Ratify an Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. Trenton: J.R. Freese, 1865.

Even with the outcome of the Civil War apparent to all, the New Jersey legislature initially refused to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment in March 1865. Although some legislators were concerned about the constitutionality of the process, others feared that passage would increase the immigration of blacks to the state. By December 6, 1865, the required number of states, including eight states of the former Confederacy, had approved the amendment, making the amendment an official part of the U. S. Constitution without New Jersey support.

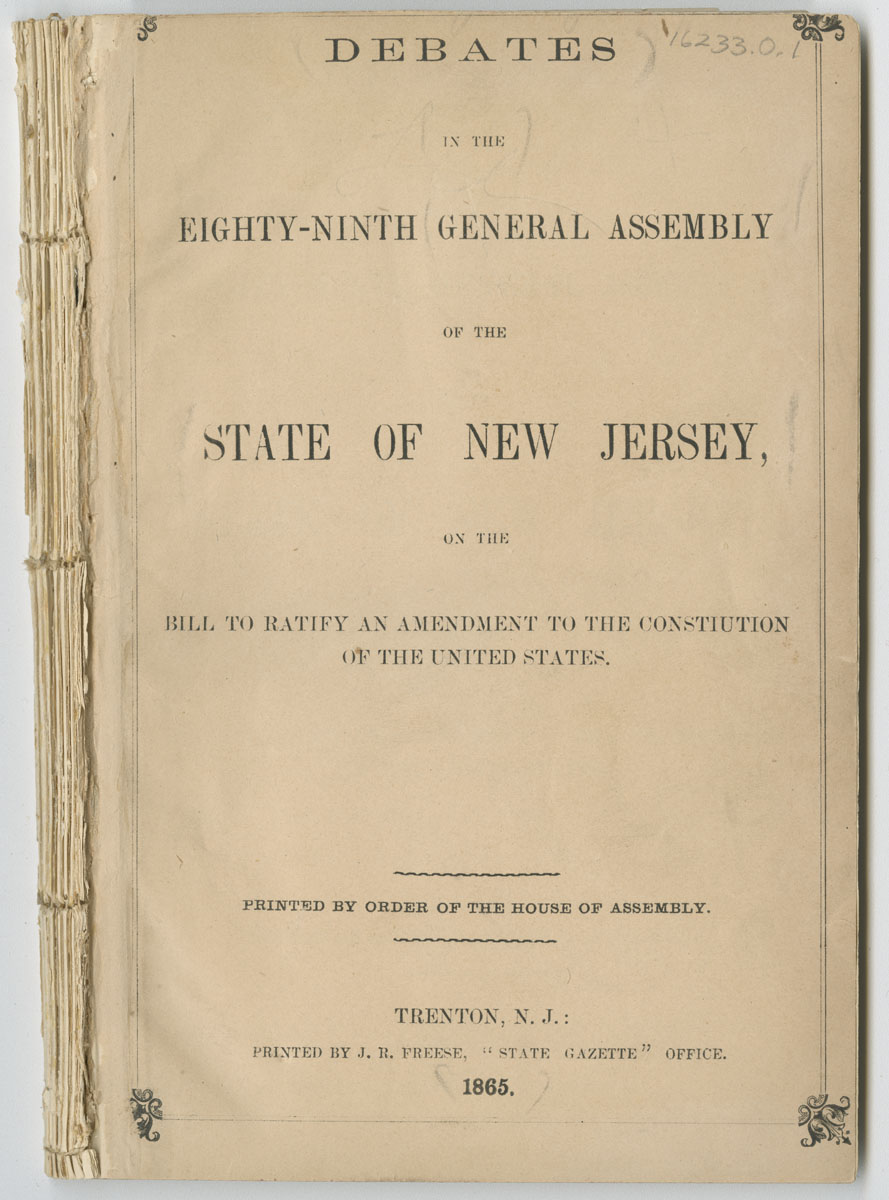

“The Election in New Jersey.” Harper’s Weekly (November 25, 1865).

While Pennsylvania was among the first states to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment in February 1865, Democrats in the neighboring state of New Jersey opposed ratification. As this cartoon shows, the amendment’s opponents in the New Jersey General Assembly incited fear that passage would lead to increased black migration northward and racial miscegenation. The Democratic Party also attempted to win support by paying the steep poll tax for white voters who would not be swayed solely by racial motives. However, the state’s November 1865 election resulted in a new state legislature composed largely of Republicans and other Unionists. As a result, New Jersey ultimately ratified the amendment in January 1866, when the new legislature took office.

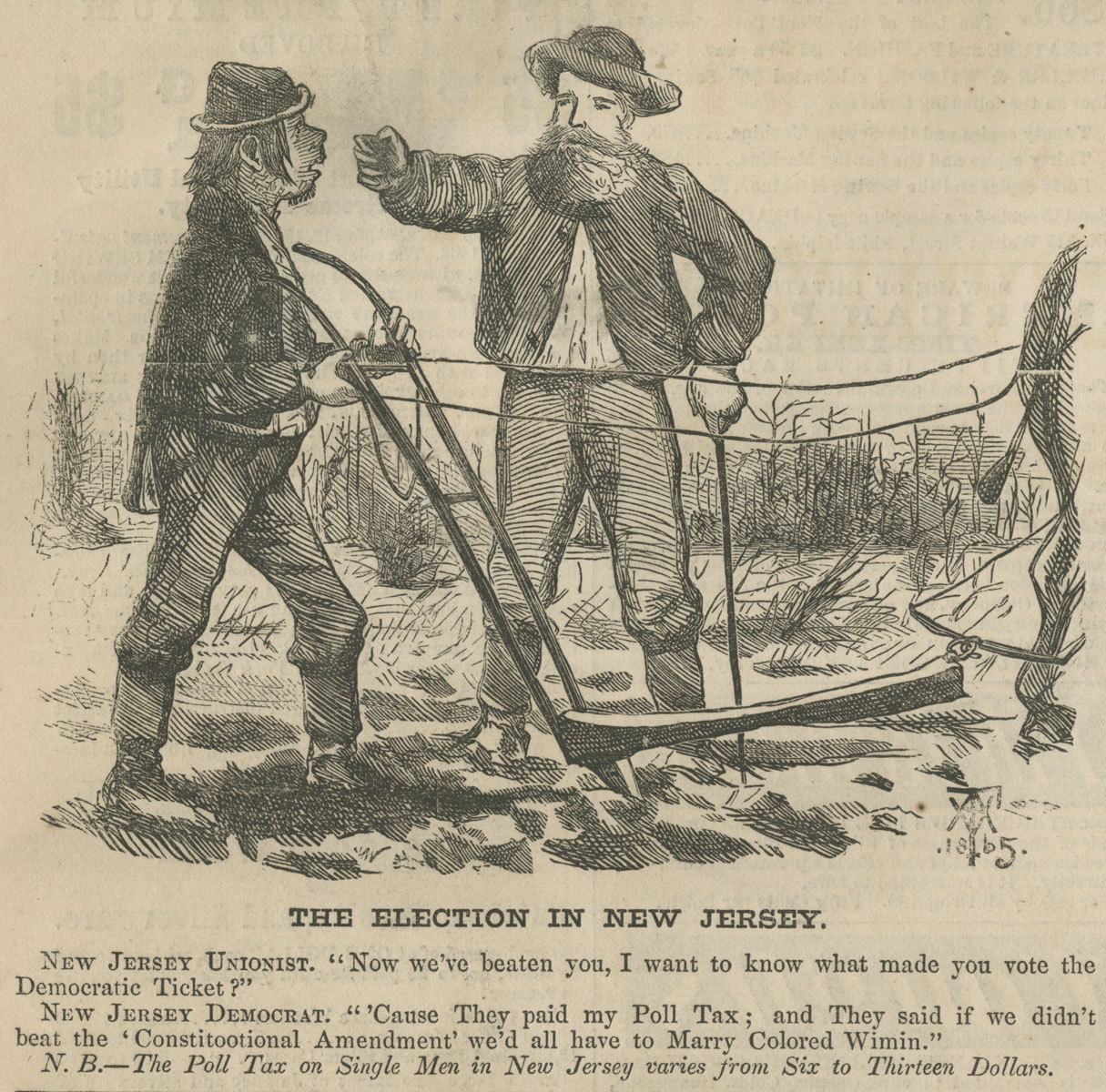

Frederick Douglass, Will Deliver the Third Lecture of the Course before the Social, Civil and Statistical Association of the Colored People of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, 1865.

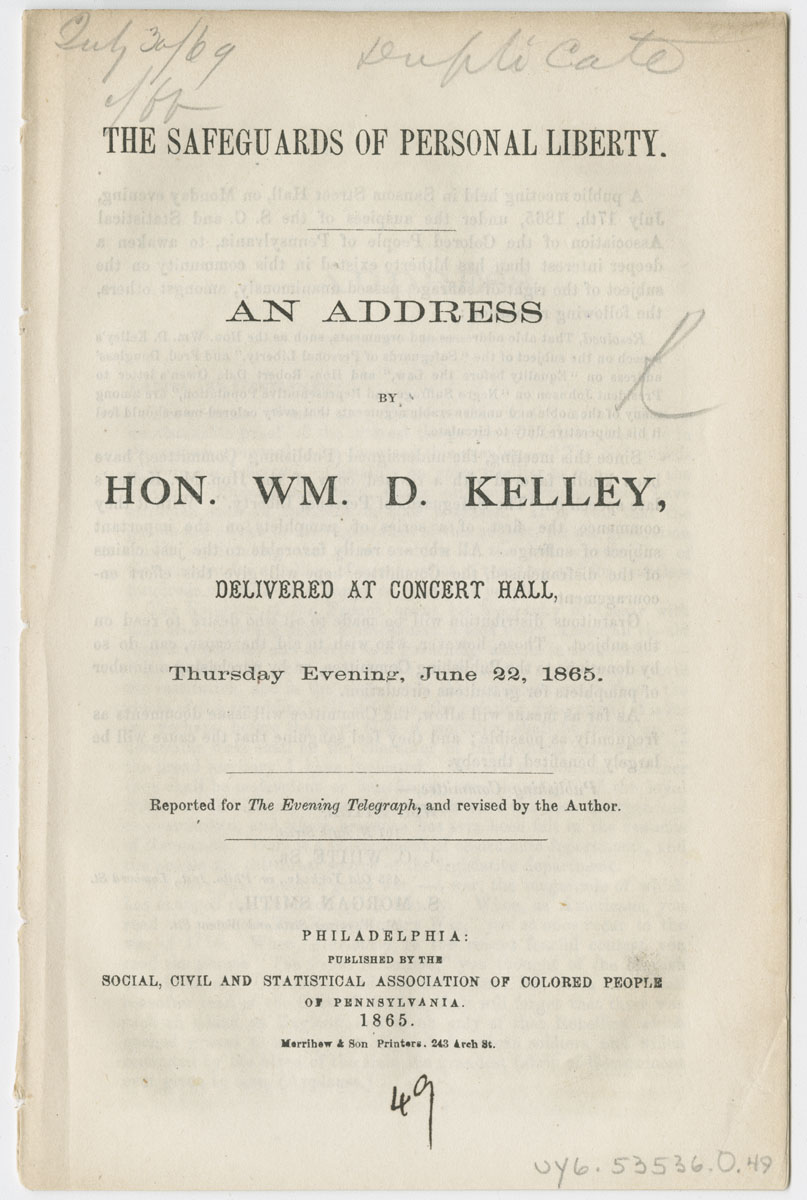

William D. Kelley. The Safeguards of Personal Liberty. Philadelphia: Social, Civil and Statistical Association of the Colored People of Pennsylvania, 1865.

William Still founded the Social, Civil and Statistical Association in 1860 to combat prejudice and to promote racial equality. In order to entice audiences, the association often held events which combined serious lectures with popular entertainment. In addition to leading the campaign to desegregate Philadelphia streetcars during the 1860s, the association organized lectures to encourage support of the new constitutional amendments, such as this speech by Congressman William D. Kelley on the need for black male suffrage.

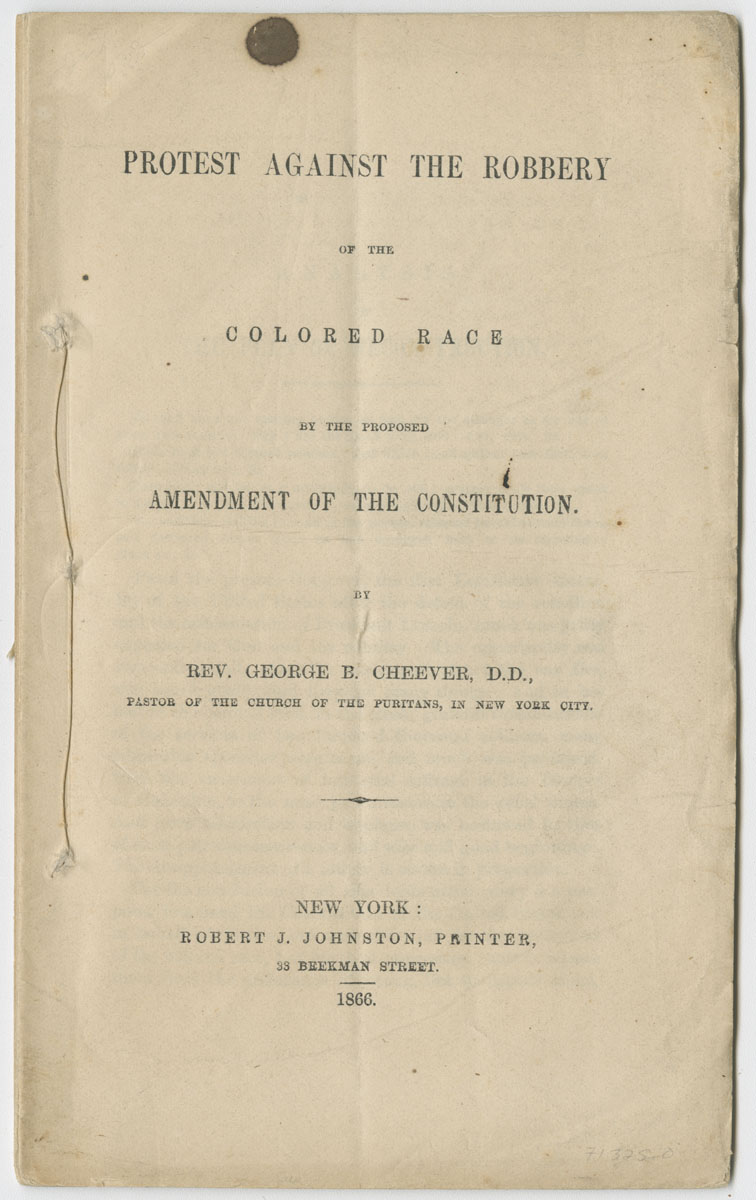

George Cheever. Protest against the Robbery of the Colored Race by the Proposed Amendment of the Constitution. New York: Robert J. Johnston, 1866.

The Rev. George Cheever (1807-1890), a Presbyterian clergyman and fervent abolitionist, was one of many Northern civil rights activists who opposed the proposed Fourteenth Amendment since it granted citizenship without suffrage. Cheever felt that many Northern supporters of the amendment were pandering to former slave holders by encouraging the passage of a watered-down amendment in exchange for their rejoining the Union.

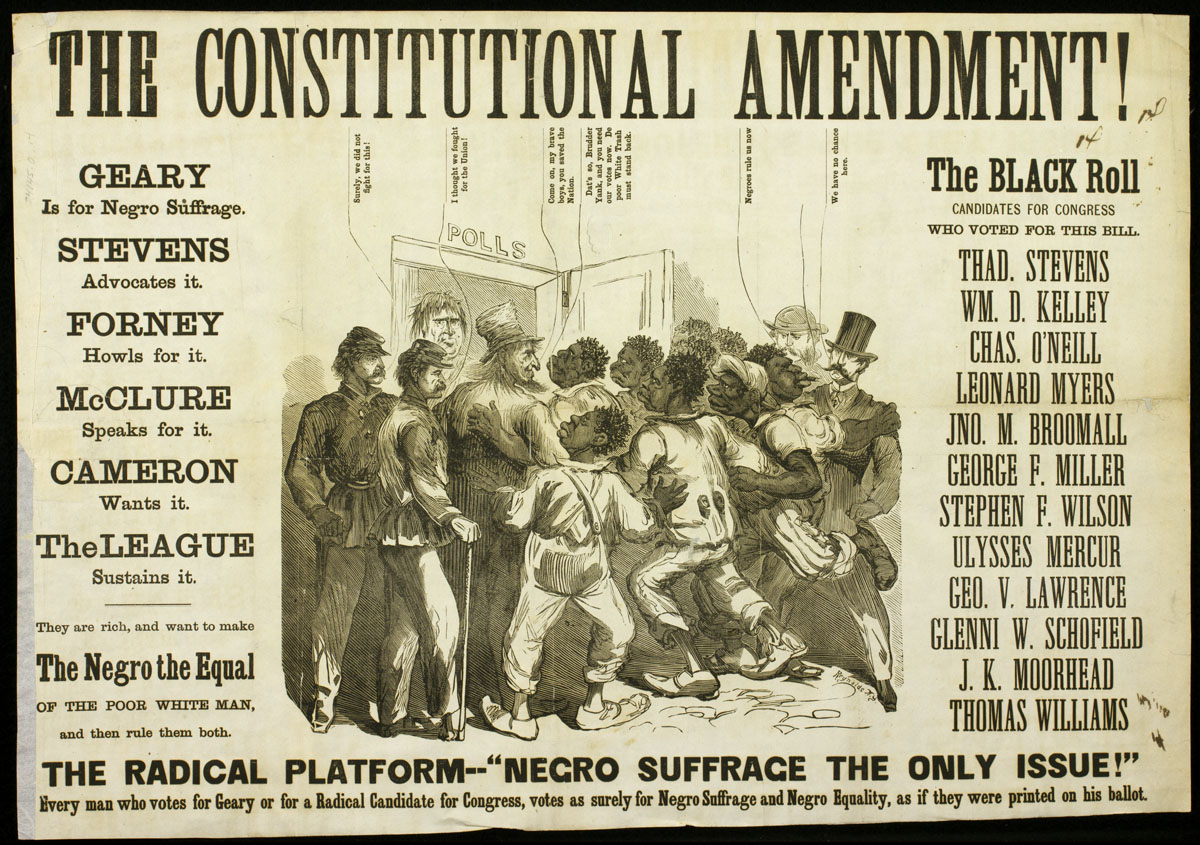

The Constitutional Amendment! Geary is for Negro Suffrage. Philadelphia, 1866.

Since the Fourteenth Amendment failed to address voting rights, the issue of black male suffrage remained a lightning rod in Northern political campaigns. Radical Republicans, a faction within the Republican Party, unrelentingly supported suffrage and other civil rights for African Americans on moral grounds. Anti-Republican campaign propaganda such as this broadside fanned fears about the party’s platform. In this depiction, working-class Irish immigrants and African Americans comprise an unruly crowd which is supposedly unfit for citizenship.

Pennsylvania gubernatorial candidate John W. Geary (1819-1873) championed extending the franchise to black men, who were overwhelmingly supporters of the Republican Party. Like many other moderate, white Republicans, Geary favored African American suffrage in order to insure that the party remained in power rather than out of concern for black rights.

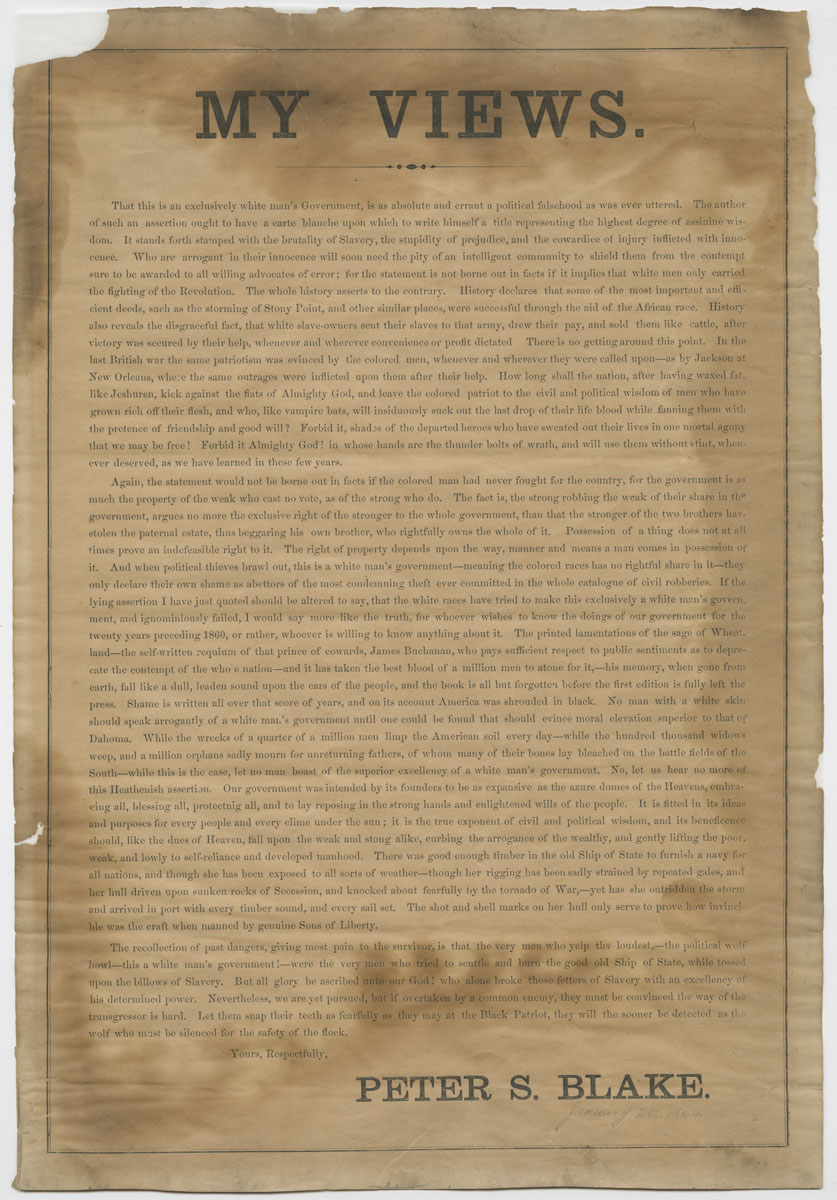

Peter S. Blake. My Views. 1866.

Peter S. Blake argued for African American equality in this broadside as well as in letters to the editor of The Christian Recorder. He likely wrote in protest of Democratic attempts in Congress and state legislatures to prevent black male suffrage. A Civil War naval veteran who was born free in Wilmington, Delaware, Blake stressed the important role that African Americans had played in helping to forge the nation, particularly during times of war.

Reconstruction and the Relations of the Races in the United States: Letter from a Committee at Oberlin to Gen. J.D. Cox, the Union Candidate for Governor. Columbus: Ohio State Journal Steam Press, 1865.

This pamphlet documents the exchange between a self-appointed committee of Ohioans and gubernatorial candidate Jacob D. Cox on his views of Reconstruction. Cox’s letter established him as a supporter of President Andrew Johnson’s anti-black suffrage platform, and further suggested that the races should live separately. Cox partly dismissed the committee’s concerns for black suffrage since they were not empowered by an incorporated organization such as a political party. While Cox had enough supporters to win election to one term of office, Ohio Radical Republicans insured that the governor elected in the 1867 elections was more sympathetic to the extension of civil rights to black Ohioans.

Daniel Clark. Suffrage of Loyal Black Men, Both a Duty and Necessity. Washington: H. Polkinhorn & Son, Book and Job Printers, 1866.

New Hampshire Congressman Daniel Clark was one of many in the Republican Party who believed that African American men had earned the right to vote through their patriotic military service during the Civil War. Basing the right to suffrage on military service excluded both black and white women.

Inaugural Address of Governor Wm. M. Stone, to the Eleventh General Assembly of the State of Iowa. Des Moines: F. W. Palmer, 1866.

William M. Stone devoted much of his second inaugural speech to Reconstruction and the expansion of civil rights for African Americans. As he entered his second term as Iowa governor, the U. S., Congress was debating the civil rights legislation that would ultimately lead to the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment. Stone argued that African Americans deserved equality and male suffrage because of their “unwavering fidelity to the Union” and courage on the battlefield. Although Stone praised Iowans for eliminating most of the state’s Black Codes from its law books, he urged them to lay aside prejudice toward African Americans. Stone also supported striking the word “white” from the Iowa constitution’s language regarding suffrage rights, an act that was accomplished in 1868.

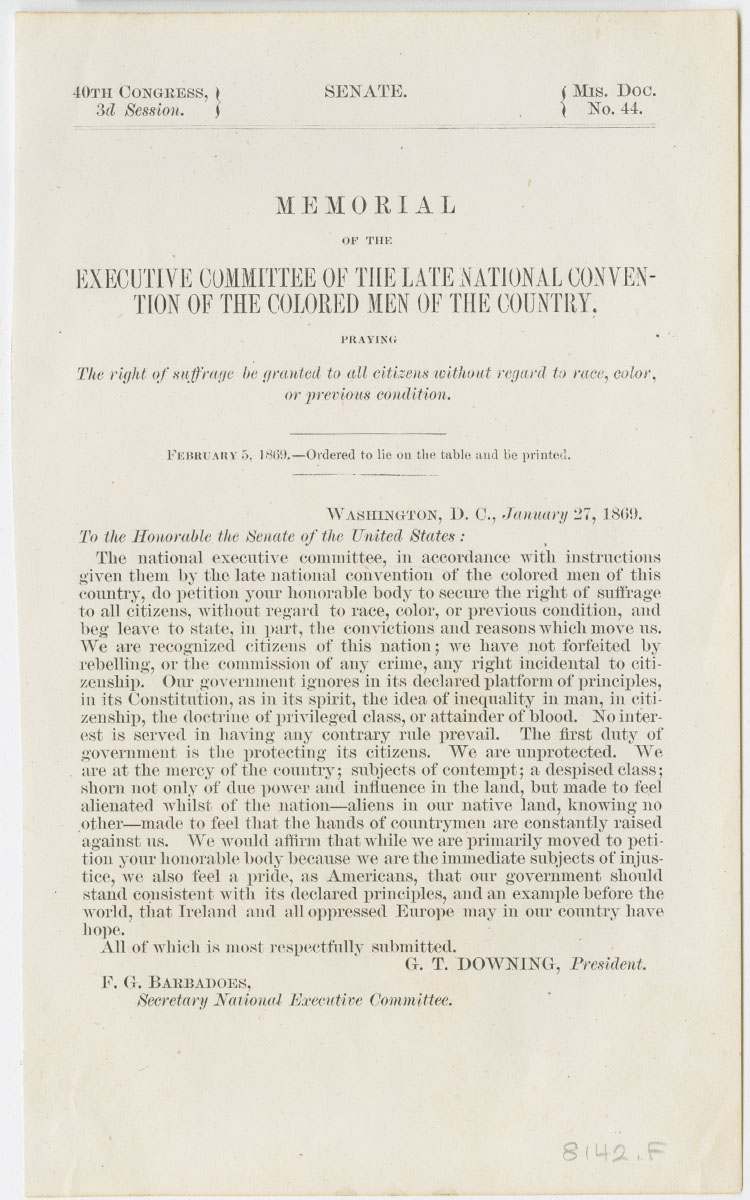

National Convention of the Colored Men of America. Memorial of the Executive Committee. Washington, DC, 1869.

George T. Downing, president of the National Convention of the Colored Men of America, submitted this petition on suffrage to Congress shortly after the convention’s 1869 meeting. The petitioners’ language pointedly emphasized their status as citizens, established by the Fourteenth Amendment in 1866, as justification for the franchise.

James C. Beard. The Fifteenth Amendment. Celebrated May 19th 1870. New York: Thomas Kelly, 1870.

African American and white civil rights activists held massive celebrations throughout the country on the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment. Supporters believed that the power of the ballot box would allow African Americans to repeal discriminatory laws and to elect officials who would protect them from state and extralegal violence. Pictured here is the Baltimore celebration, reportedly the nation’s largest with more than 20,000 participants.

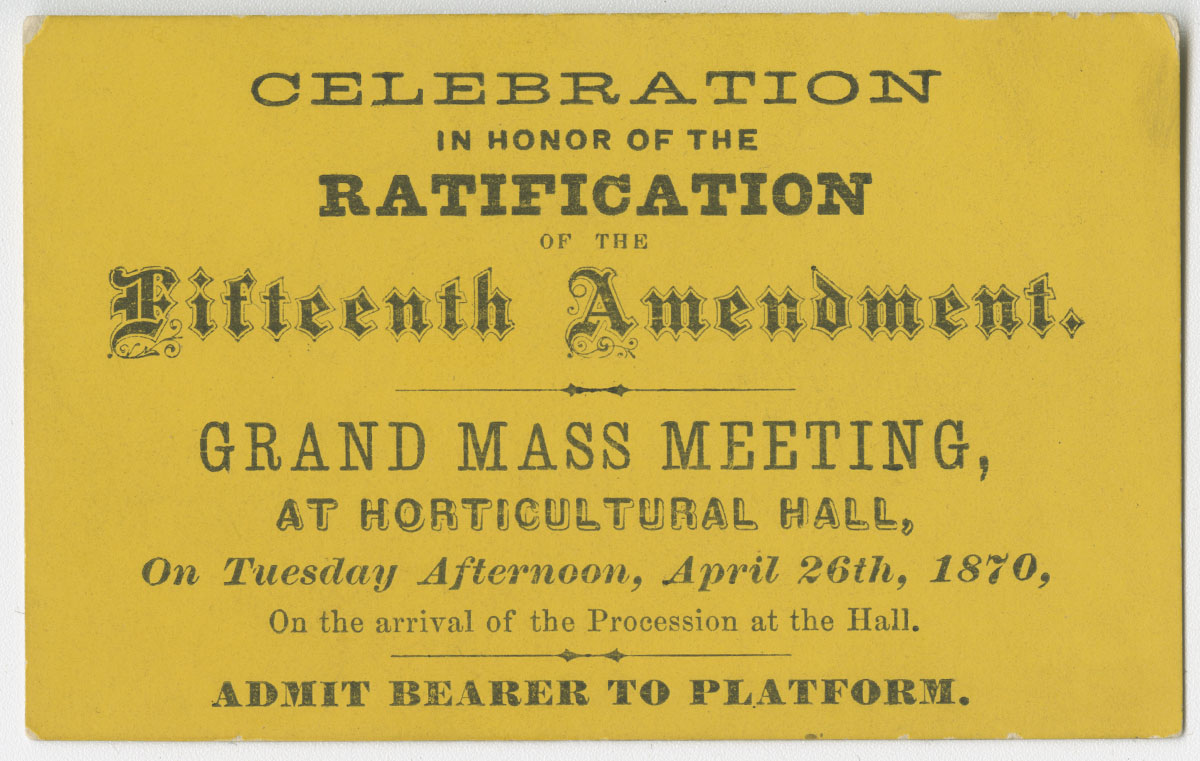

Celebration in Honor of the Ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. 1870. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

The Fifteenth Amendment celebration in Philadelphia lasted for more than five hours. Festivities included marching bands, speeches, and a parade. Included in the procession was a wagon that held a printing press which reproduced copies of the amendment for distribution.

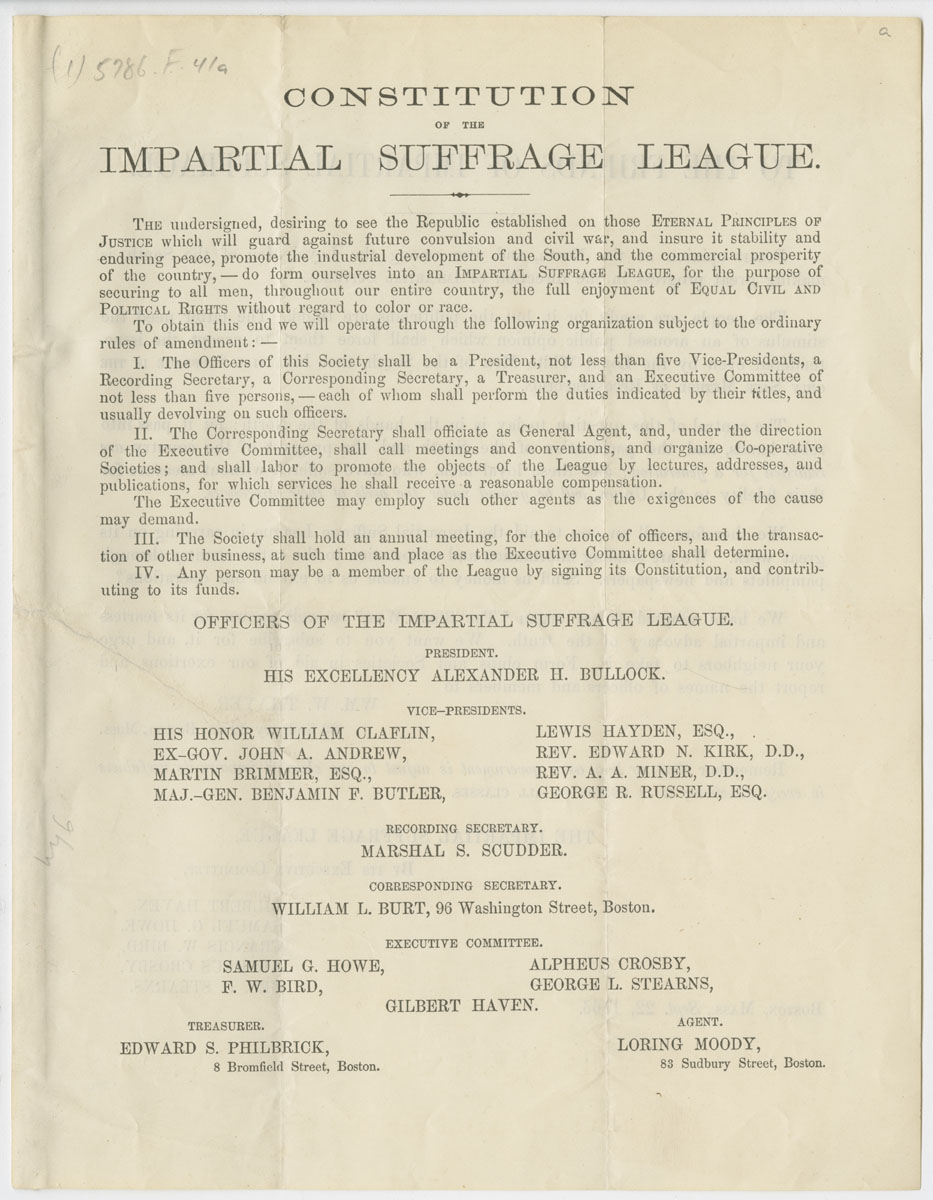

Constitution of the Impartial Suffrage League. Boston, 1866.

The Impartial Suffrage League was founded in Boston in 1866 by male abolitionists and businessmen, including Samuel Gridley Howe and Benjamin Butler. Notably absent was abolitionist and Bostonian William Lloyd Garrison, whose championing of black civil rights ended with the abolition of slavery. League members expressed support for women’s suffrage, but the league’s constitution was confined to attaining black male suffrage, and its leadership consisted only of men.

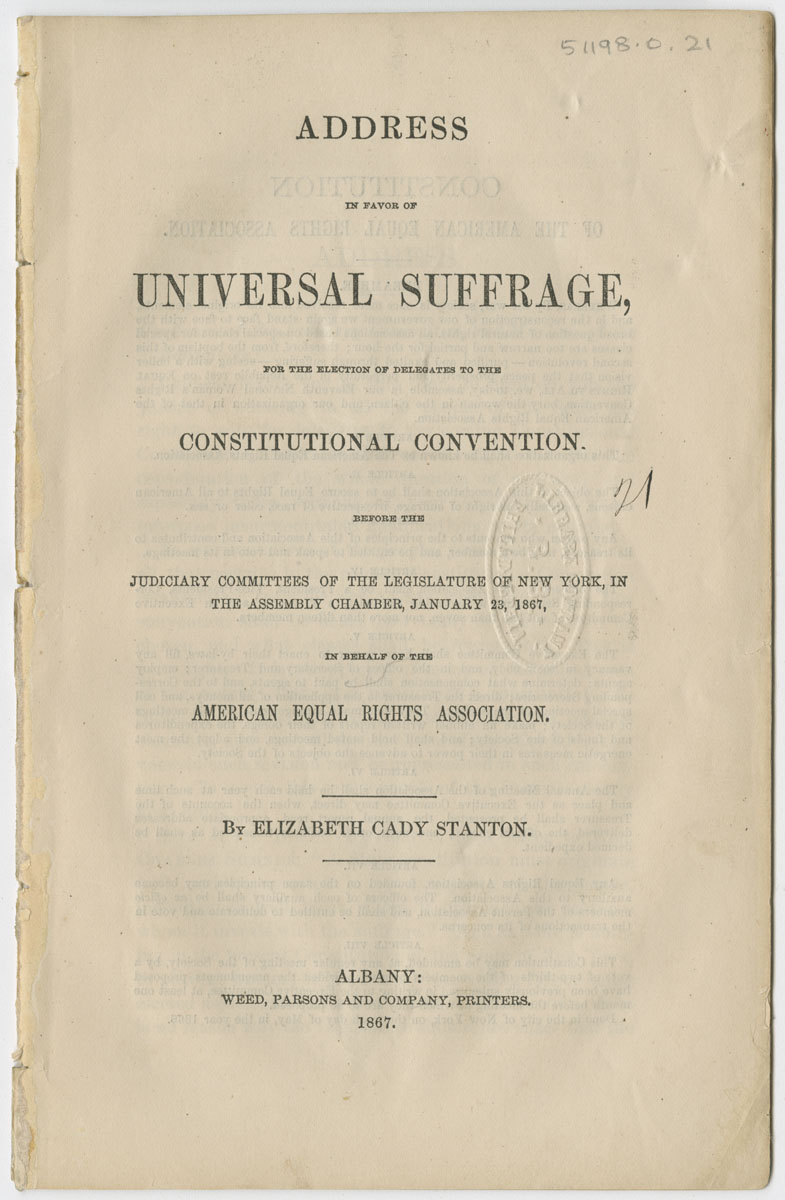

Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Address in Favor of Universal Suffrage. Albany: Weed, Parsons and Company, 1867.

Suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton initially supported voting rights for black men, as she expressed in this address. However, Stanton objected to giving uneducated former slaves the vote before white women. By the 1868 American Equal Rights Association Convention, Stanton refused to endorse the Fifteenth Amendment unless it covered women as well.

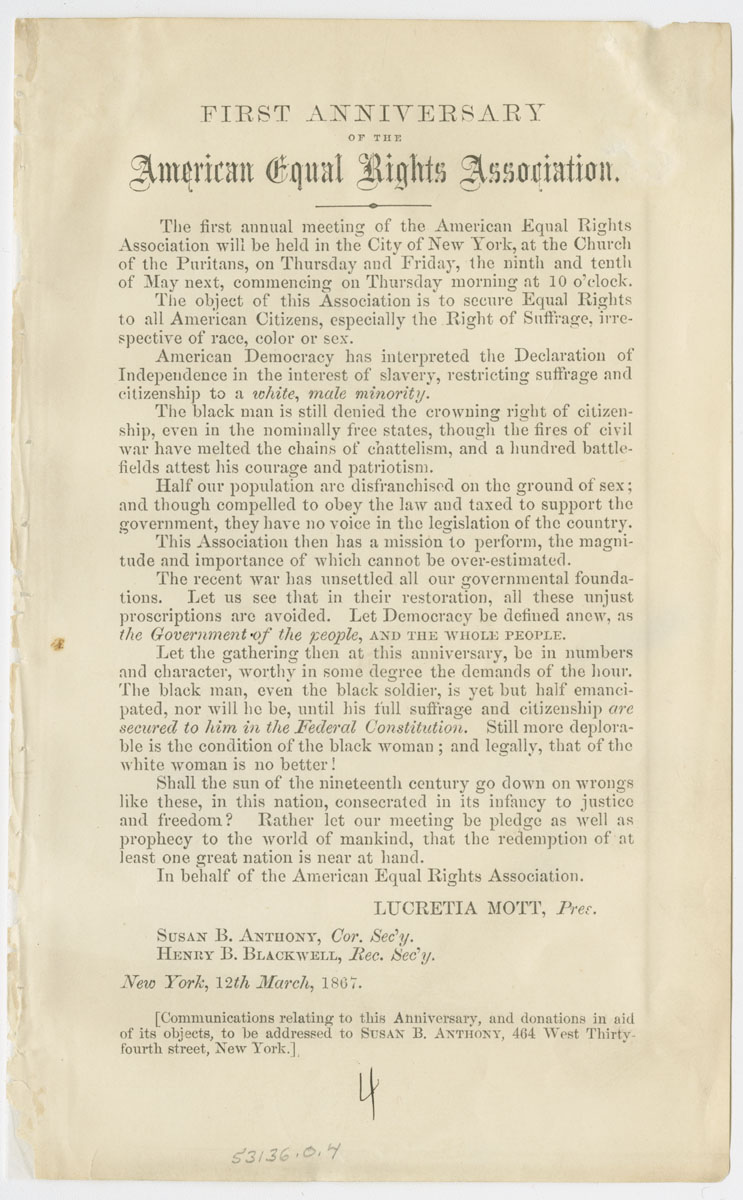

First Anniversary of the American Equal Rights Association. New York, 1867.

The American Equal Rights Association was founded in 1866 by an interracial group of men and women in order to campaign for black men’s and women’s suffrage. Several Northern black women, including Harriet Forten Purvis, Sojourner Truth, and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, were among the founders. While Frederick Douglass and George T. Downing supported the cause of women’s suffrage, the issue divided the black community. Some black men, including Robert and Harriet Purvis’s two sons, believed that politics was a male domain and that conventional gender roles reinforced the race’s progress towards being civilized Americans.

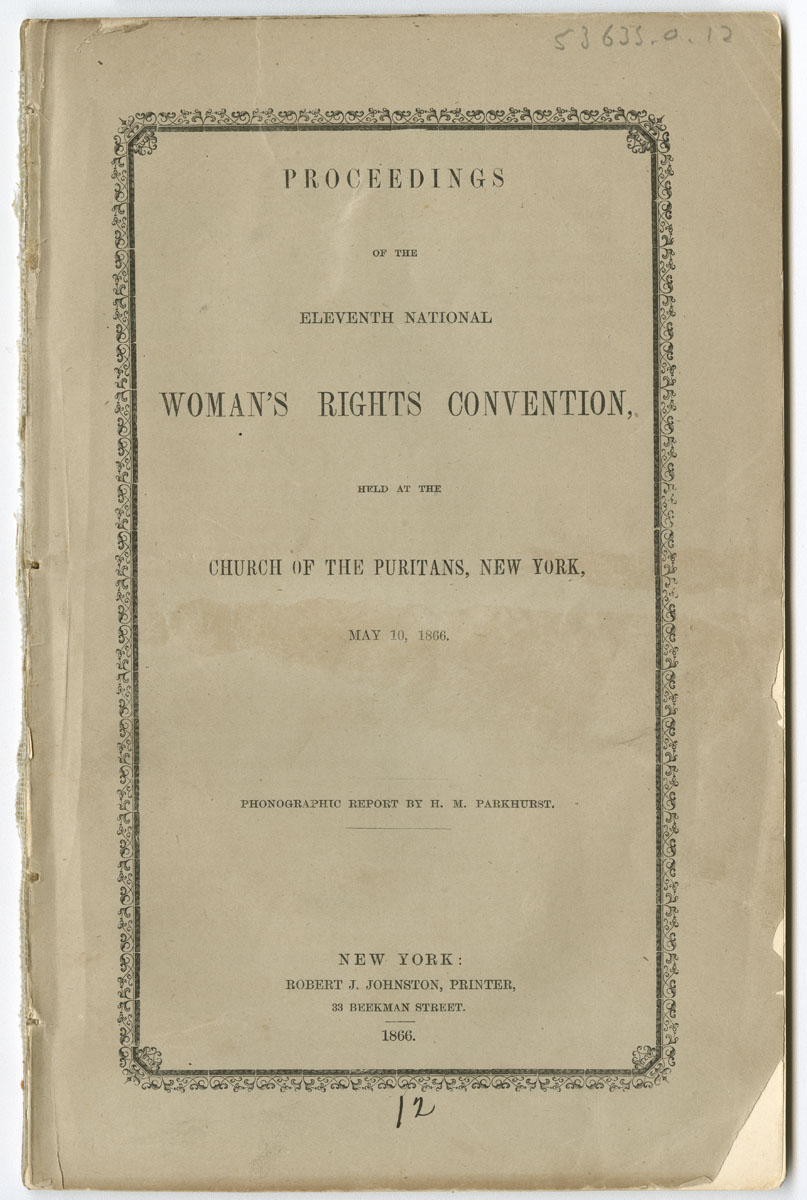

Proceedings of the Eleventh National Woman’s Rights Convention. New York: Robert J. Johnston, 1866.

The 19th-century women’s rights movement grew out of the activism of women abolitionists, who learned how to fundraise, organize, and market political protest. Abolitionist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was also a supporter of the movement and spoke at several women’s rights conventions, including this one in New York City. Noting the double discrimination faced by black women, Harper urged the convention not to abandon its support of rights for African Americans. Harper’s pleas were ultimately in vain as, in 1869, leaders of the women’s rights movement allied themselves with Southern segregationists in pursuit of white women’s suffrage.