The Photographs

As physical objects, the photographs created by John Frank Keith yield important information about not only his photographic activity, but also the history of photography in early 20th century America.

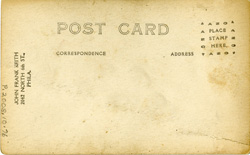

Keith printed all of his photographs on postcard stock measuring 3.5 x 5.5 inches, like the one shown here.

Keith printed all of his photographs on postcard stock measuring 3.5 x 5.5 inches, like the one shown here.

Postcard supports were a popular choice for commercial photographers in the early-to-mid 20th century because they were cost effective, sturdy, readily available for purchase (with the option of including the photographer's imprint), and well-liked by consumers. Keith probably used them because they were easy to obtain and desirable for his subjects, who would share postcards with family members and friends.

Keith used a variety of postcard paper by different manufacturers, including Kruxo, Cyko, Defender, Azo, and Artura (the latter two Kodak-owned brands). Postcard manufacturers occasionally changed the design elements of their cards as a way to keep their product fresh and distinct. These design changes provide clues about the approximate dates of Keith's photographs. For example, the stamp box ("Cyko" printed in decorative script surrounded by the words "Place Postage Stamp Here") shown below is a unique design of the Cyko brand manufactured by the Colombia Photo Paper Company. The earliest known date of manufacture of this specific design is July 19151, therefore Keith could not have printed the photograph on this card before July 1915. While this method of dating neither precludes the possibility that Keith reprinted an image taken years earlier nor accounts for the long manufacturing period of some postcard papers (Kruxo manufactured one style for 11 years before altering it), it helps narrow the time period within which Keith's photographs were created.

During the early 20th century, many professional photographers who operated their own portrait studios offered prints on postcard stock to their customers. Families collected and shared these mementos, which typically cost around 5¢ each. Sitters, often wearing their finer clothes to mark a special occasion, would visit the studio and pose for formal portraits, sometimes with the use of special props or backdrops, as in the case of the portrait below.

Roma Photo Studio, Portrait of unidentified woman, gelatin silver print on postcard mount, Philadelphia: ca. 1926.

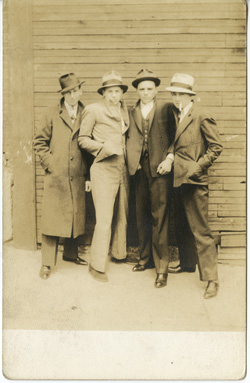

John Frank Keith practiced a more vernacular style of portraiture. He did not have a studio, and instead traveled with a hand-held camera to his subjects in their own neighborhoods. By capturing the residents of South Philadelphia and Kensington on their territory, his subjects probably felt more free to be casual in front of the camera, and sometimes even playful, such as these young men posing as gangsters with guns in their pockets.

Indeed, the informal, sometimes snapshot-like quality of Keith's images suggests that he had established a comfortable rapport with his subjects. Whether caught amidst their normal activities, such as playing cards on a stoop, or posed for a special occasion, like First Communion, Keith made a connection with the people on the other side of his camera.

John Frank Keith, Four young men posing as gangsters, gelatin silver print on postcard mount, Philadelphia: ca. 1931.

The desire to connect with people seems to have been Keith's main motivation for doing the work he did for so long, whereas notable contemporaries were motivated more by social reform, artistic achievement, or commercial success. Lewis Hine, who documented child labor and industrial workers in the early 20th century, for example, "understood the power of photography to effect social change"2 and used it to disseminate his progressive views. Another practitioner of social documentary in the early 1900s was German artist August Sander. He purposefully set out to create a photographic catalog of the people of his native town in Germany. Closer to home, George Mark Wilson in 1923 photographed immigrant communities and the changing physical landscape of Philadelphia, taking detailed notes along the way, possibly with the intention of publishing a book. Other photographers of Keith's time period who shot in a similar direct style, such as Mike Disfarmer of Arkansas, maintained a stronger business interest in portraiture, as operators of professional studios. With bookkeeping and WPA jobs to provide income and no known social reform agenda, Keith likely photographed his neighbors to fulfill his serious interest in photography, possibly supplement his income, and form relationships with his "friends" who would take his photos home to place in family albums.

1 Robert Bogdan and Todd Weseloh, Real Photo Postcard Guide: The People's Photography (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2006), 233.

2 Miles Orvell, American Photography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 73.