Section III. “Spirit and Freedom of Execution”: Lithography Arrives in Philadelphia

Although Bass Otis produced the first American lithograph in Philadelphia in 1819, it would be another nine years before the establishment of the first commercial lithographic firm in the city by looking glass and print store proprietors Kennedy & Lucas. By 1829, the trade had increased to three firms. Soon thereafter, eight lithographic presses were in operation in Philadelphia. The next decade proved an era of fluctuation for the trade in a city that was already a transatlantic center for printing. Proprietors, artists, lithographers, and printers entered and departed the increasingly viable industry. By the end of the 1830s, job work for merchants and businessmen, portraits, periodical and book illustrations, advertisements, and views (often of the Fairmount Water Works) steadily issued from the city’s lithographic presses. Philadelphia lithographers had firmly established a niche for themselves within the local printing community.

Instructions, often vague, for the lithographic process had been disseminated in this country since the first decade of the 19th century. Treatises, including a description of etching on stone in chemist James Cutbush’s The American Artist’s Manual (1814), were published and circulated in Philadelphia, an established center for scientific study and printing.

Click on the thumbnails below to browse the items in this section of the exhibition.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

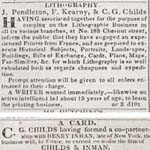

Another printing industry – newspapers – helped sustain the early lithographic trade in Philadelphia. Beginning with Kennedy & Lucas’s announcement, articles and notices, such as those displayed here, promoted the work of the establishments, announced the sales of equipment, and the dissolution, relocation, and reconfiguration of the six major firms active between 1828 and 1838, including M. E. D. Brown, John T. Bowen, and the various partnerships of C. G. Childs.

We have in this city . . . the person of Mr. [M.] E. D. BROWN, whose works in this line are now exhibiting at the Academy of Fine Arts. Without any pretensions to favoritism, they are the best kind, and fully equal to anything that has been produced in this country. . . . This gentleman’s drawing on stone as well as the printing (which is under his management) possesses completely the requisites of the art.

“Lithography,” The United States Gazette, May 31, 1832

|

![[A View of the Fairmount Waterworks with Schuylkill in the Distance. Taken from the Mount.] ([Philadelphia: Printed and published by J. T. Bowen, 1838]). Crayon lithograph, hand-colored.](images/thumbs/2th3.10.jpg)