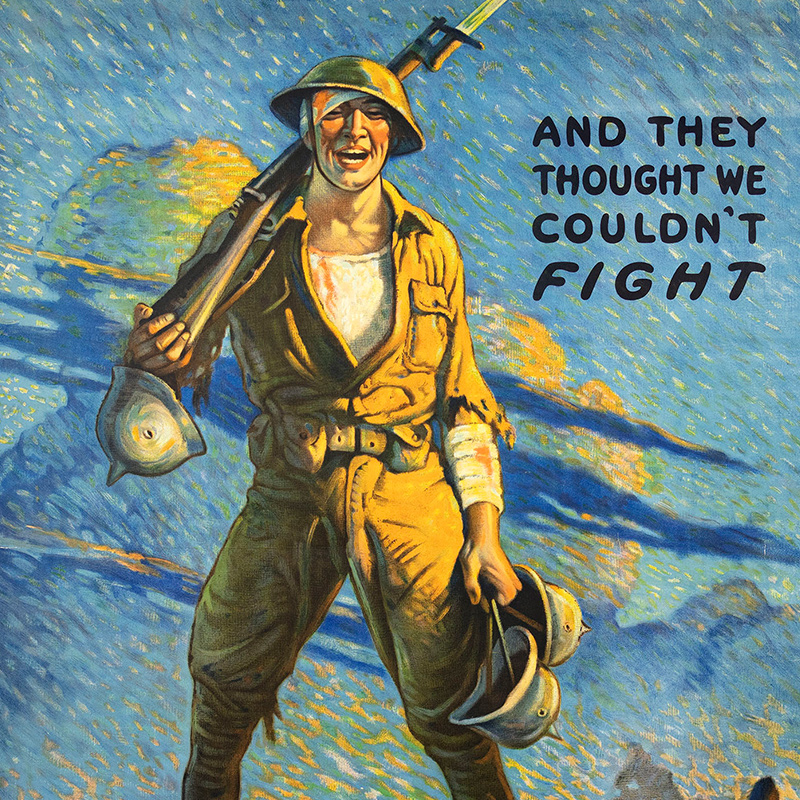

Inception, Collection, Reception: Reading the Graphic Arts Collection

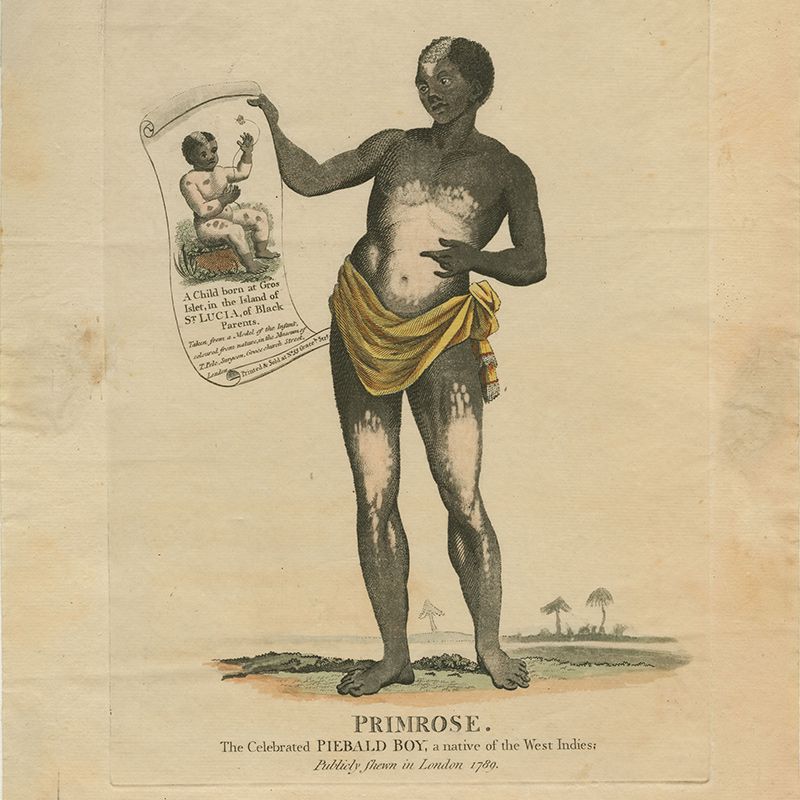

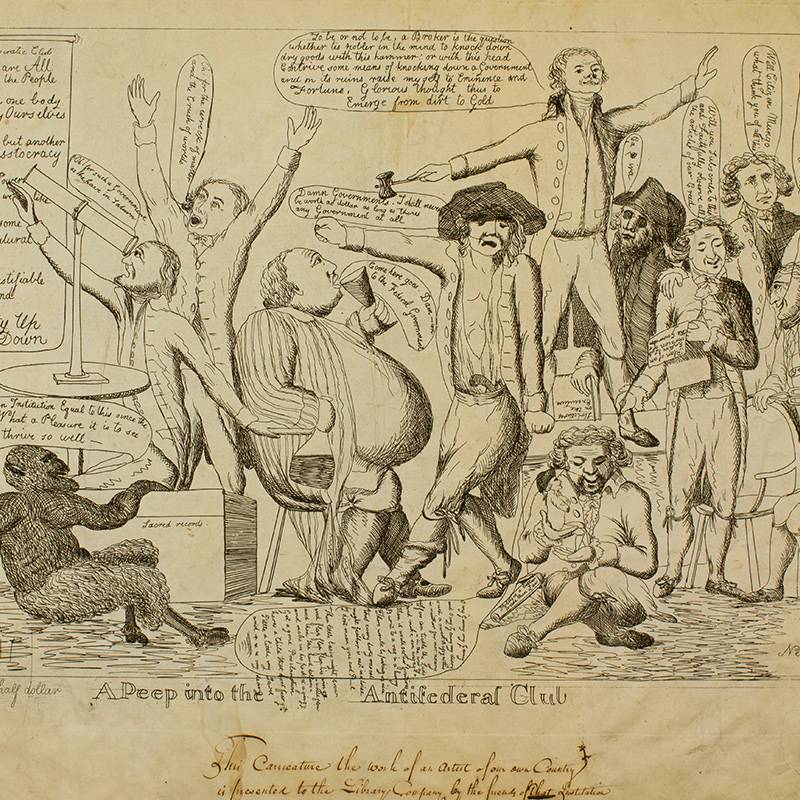

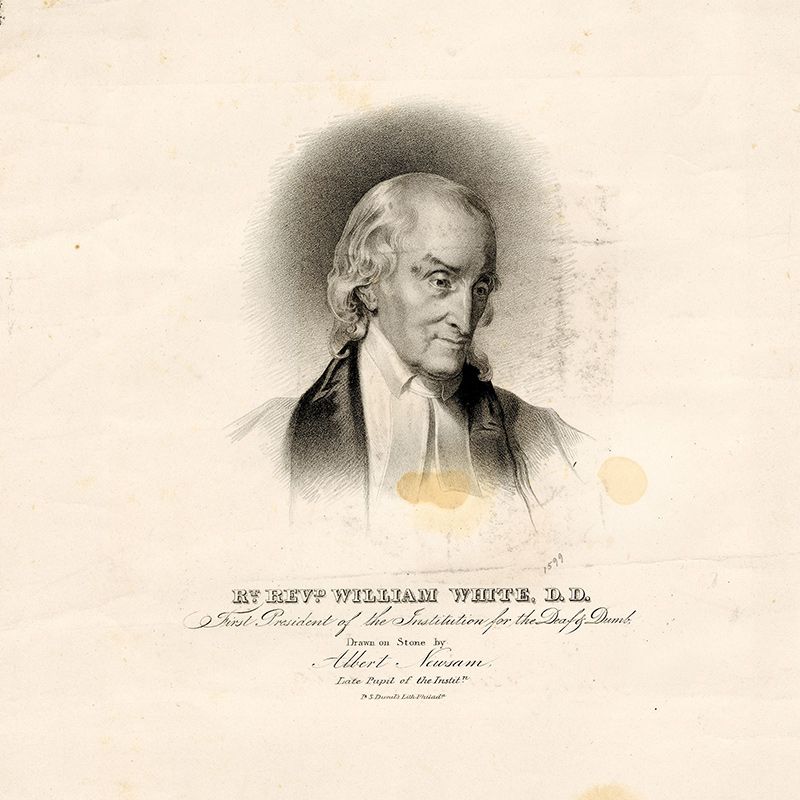

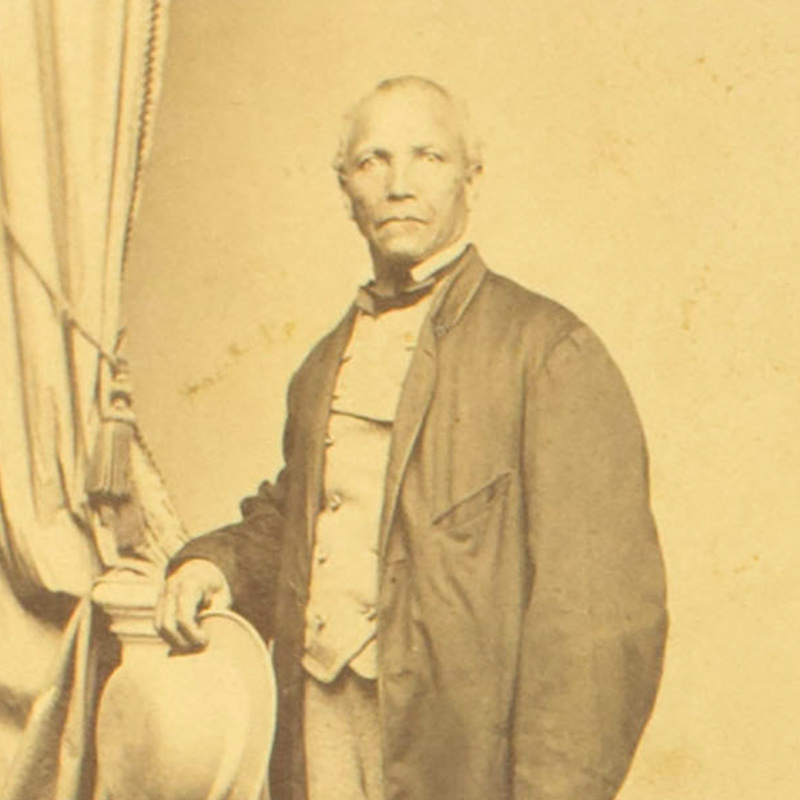

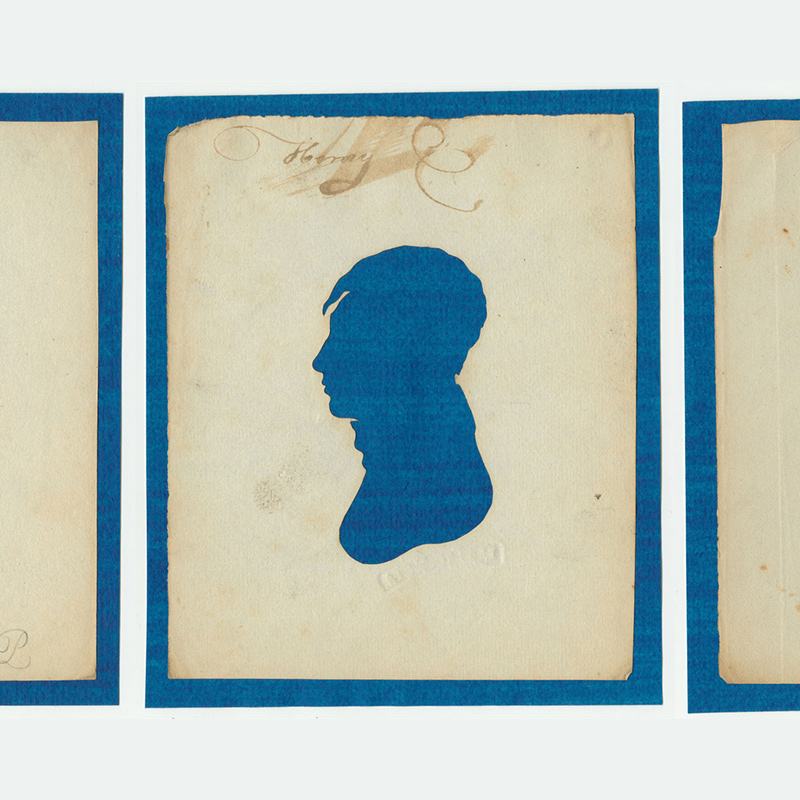

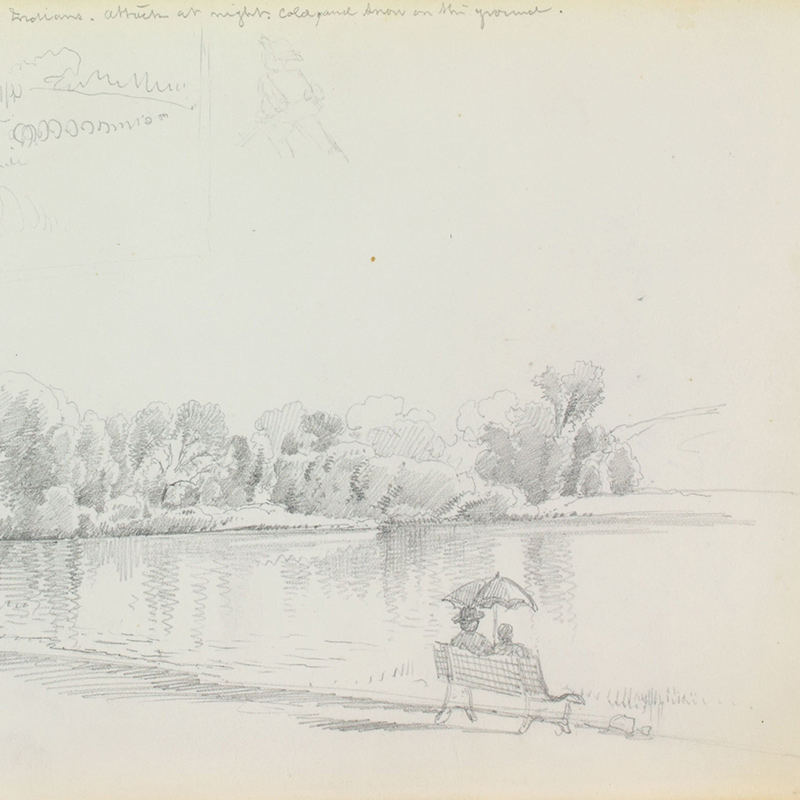

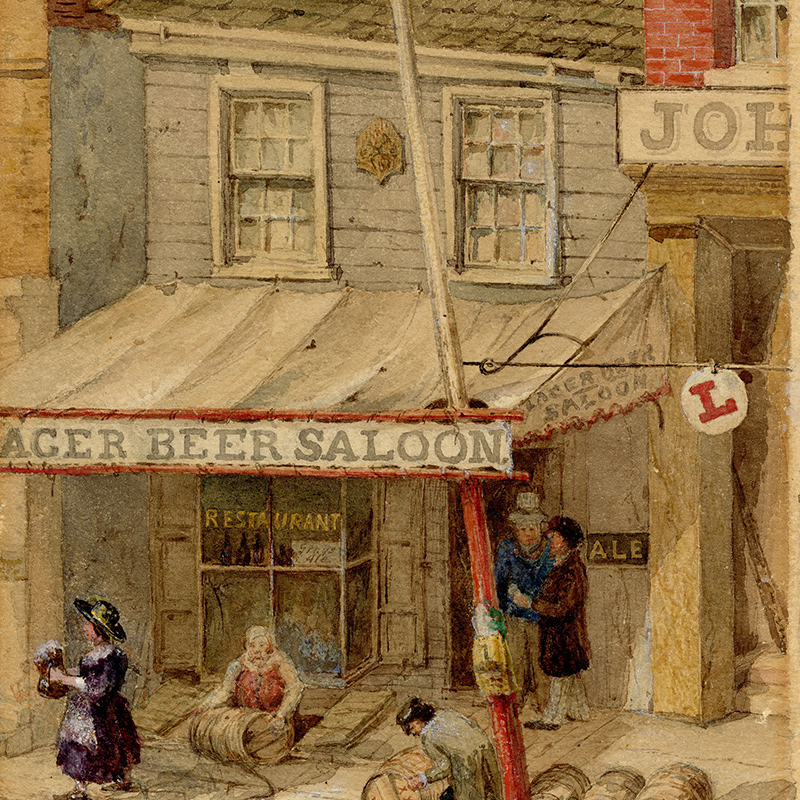

From soon after the establishment of the Library Company in 1731, the institution acquired graphic art works from Library members and patrons to foster a literate society with books and visual materials. As noted by scholars of reading, before you can learn to read, you need to learn to look. Reading a graphic art work does not only involve looking at its visual content. One must also consider its inception, collection, and reception. When the visual material is historical, the period in which it was created and acquired, and the periods of time of when it was viewed in the past and present, is part of that interpretive process.

Visually literacy is essential to be an engaged citizen. It is a safeguard to understand what we see today and a tool to understand what was seen by those previously. Through a selection of graphic materials received by the Library Company over its first two centuries as a public library, this section invites you to look closely and think about how you see, value, and understand your visual world and how the generations before you saw, valued, and understood it.

Items marked with an asterisk (*) appear only in the online exhibition.

Imperfect History is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, Walter J. Miller Trust, Center for American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jay Robert Stiefel and Terra Foundation for American Art.