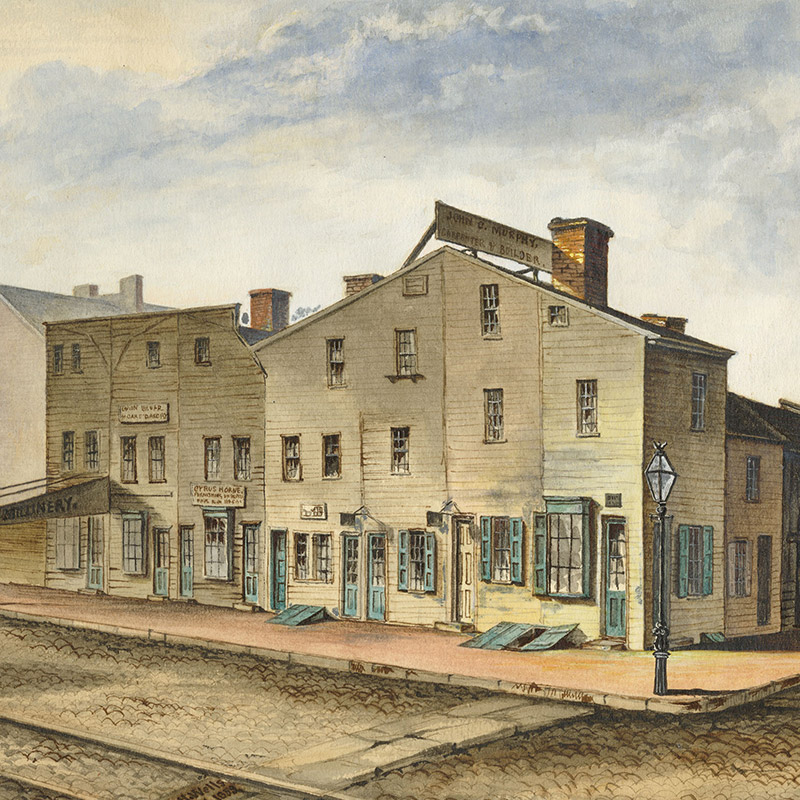

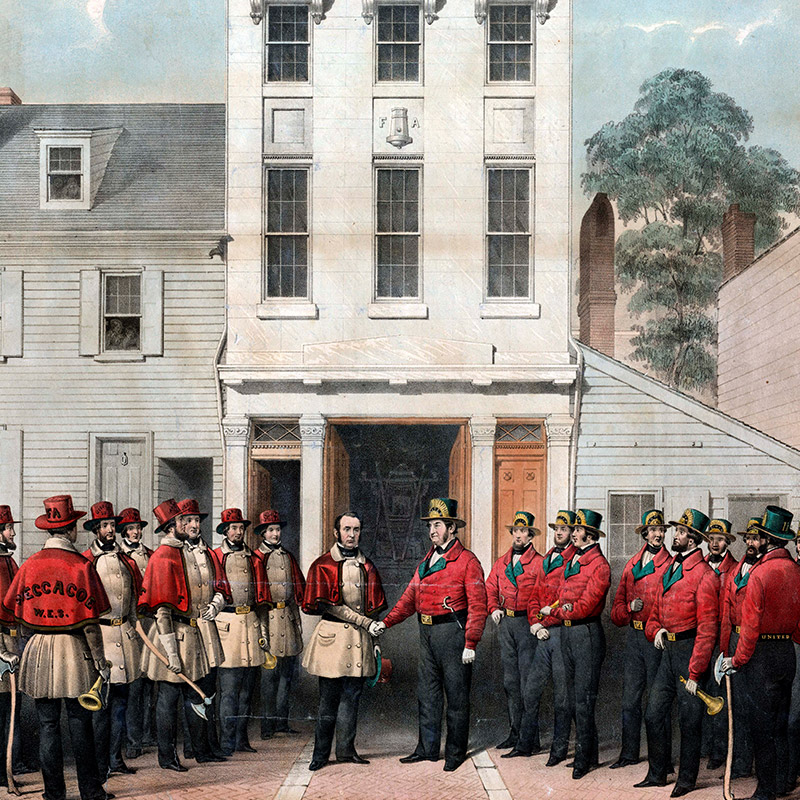

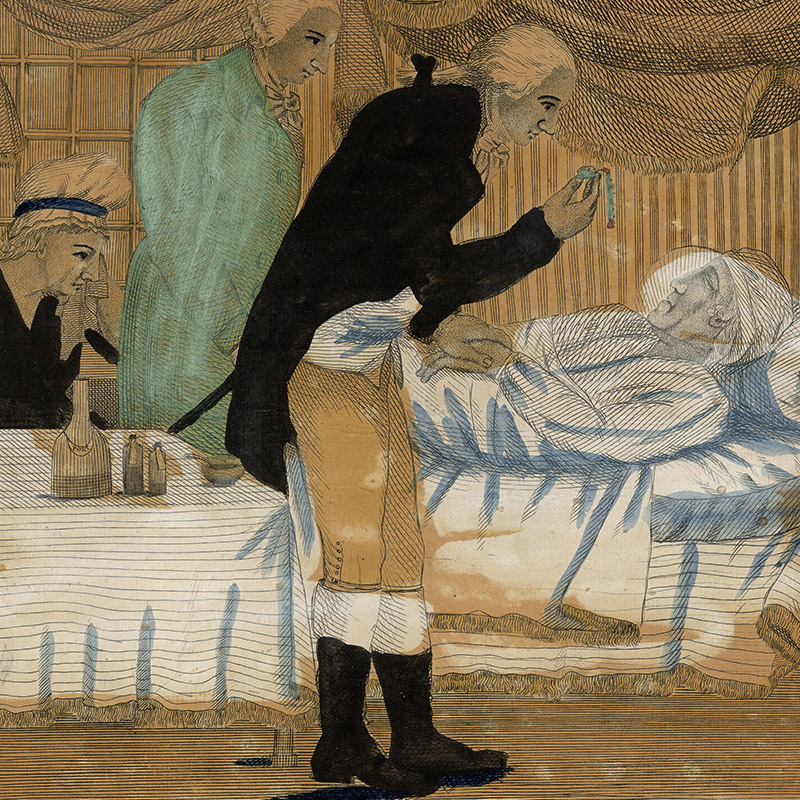

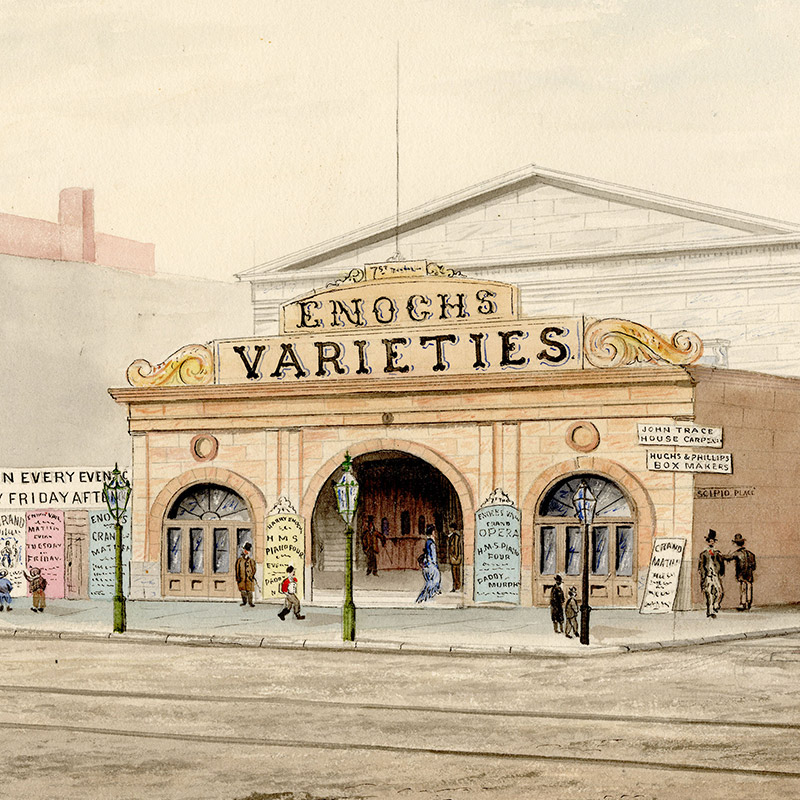

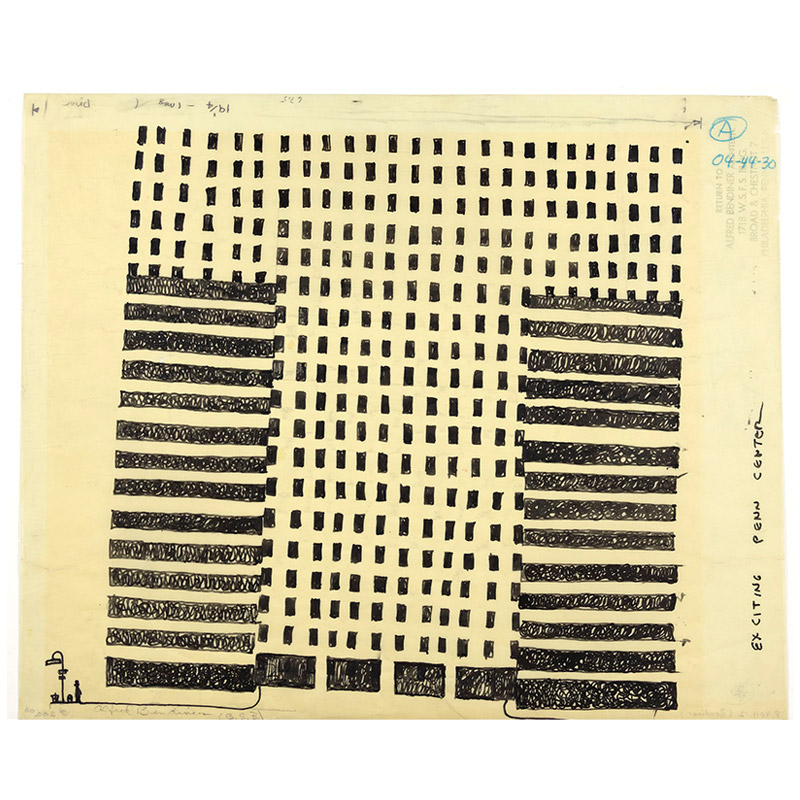

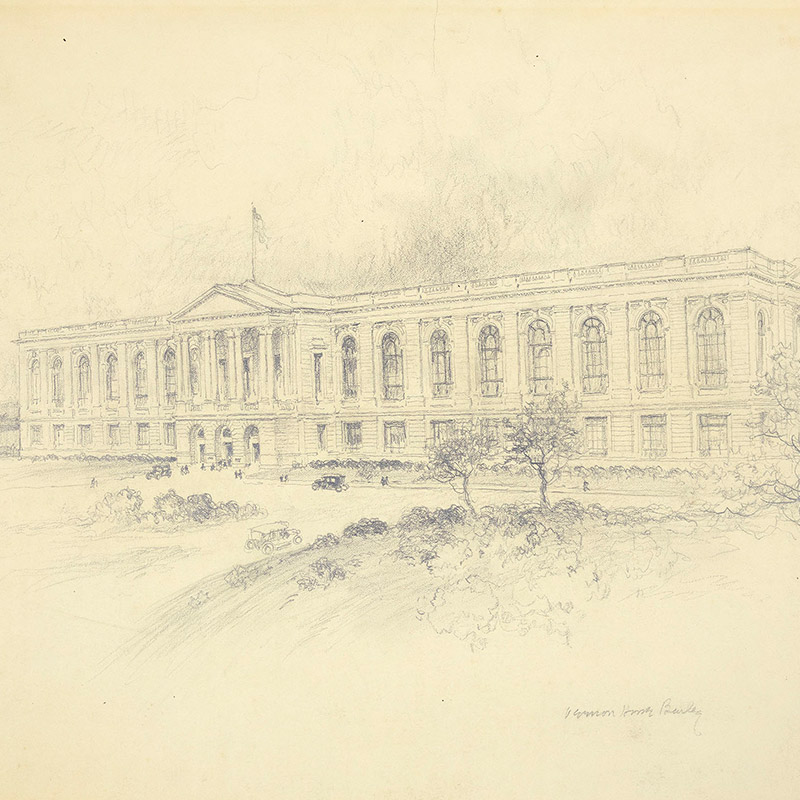

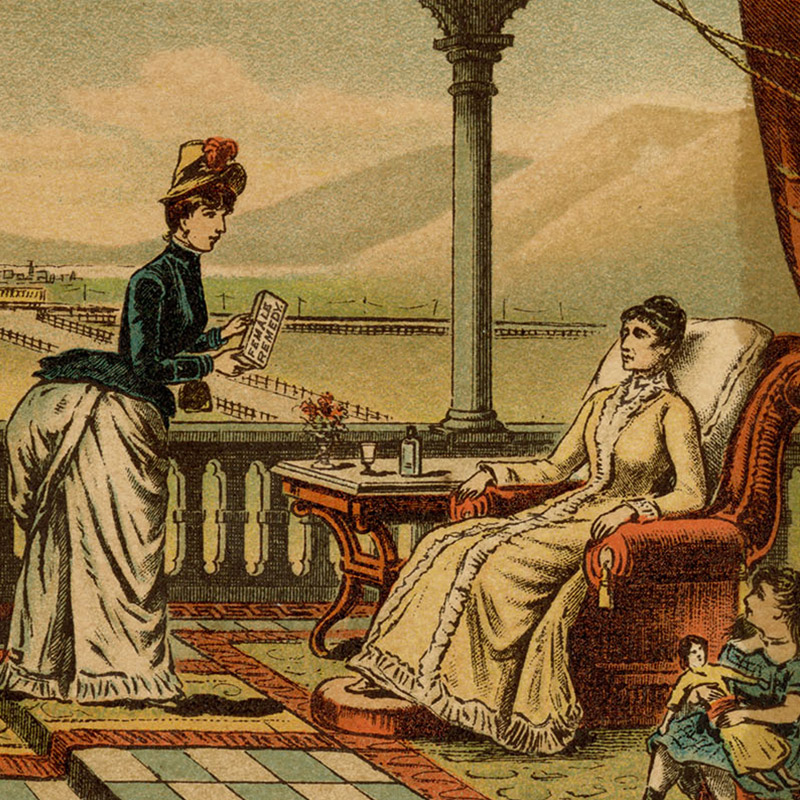

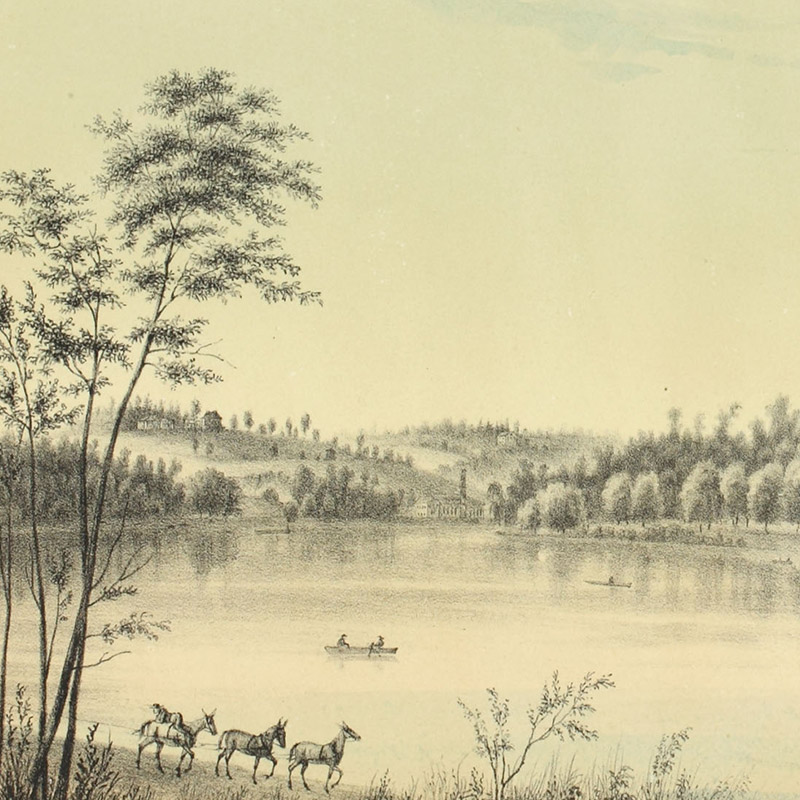

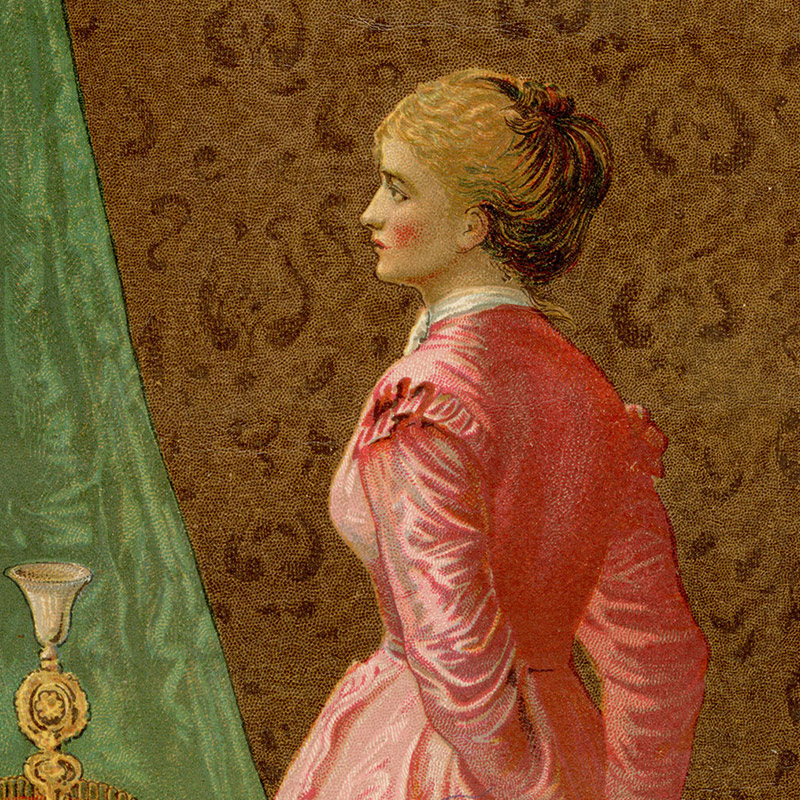

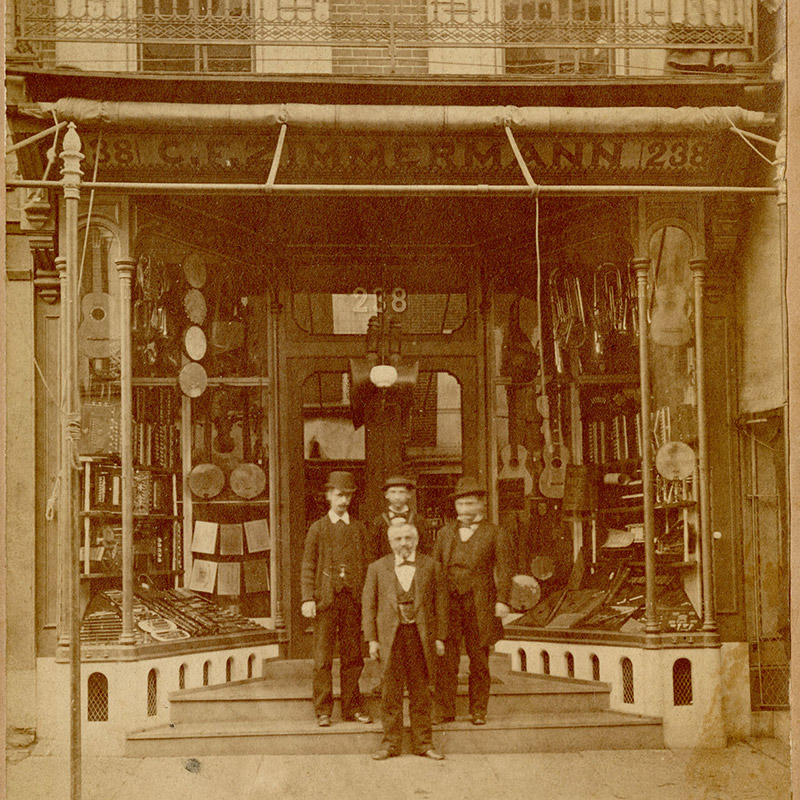

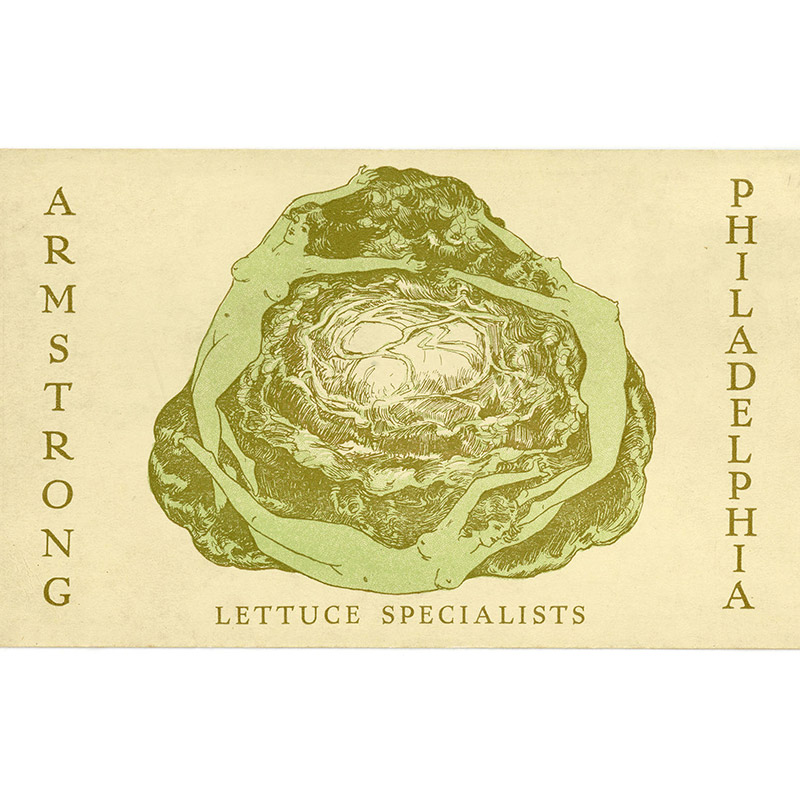

As Time Goes By: Snapshots of the Evolution of the Graphic Arts Collection, 1731-2021

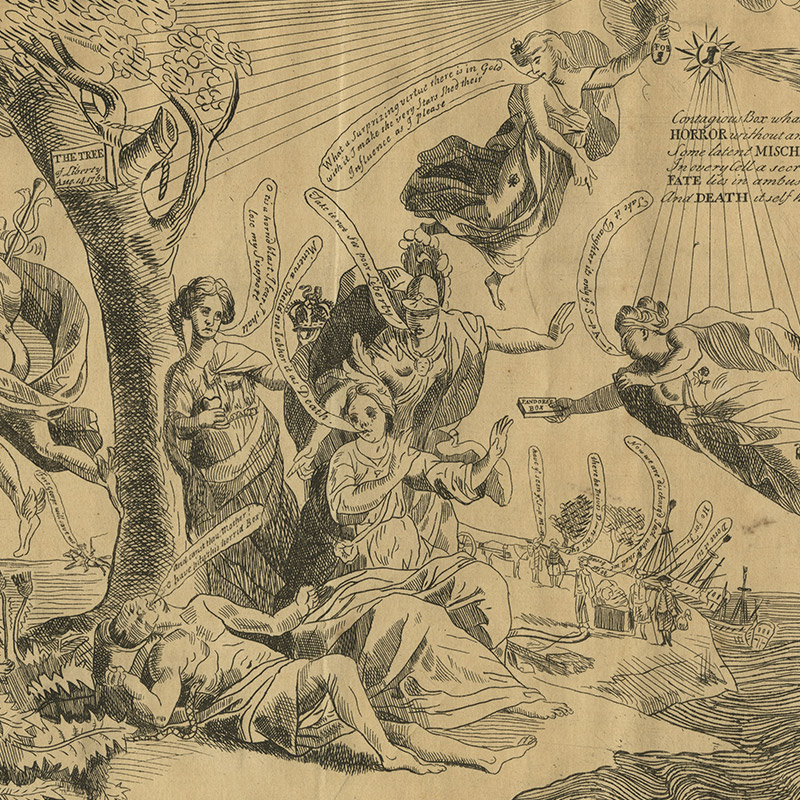

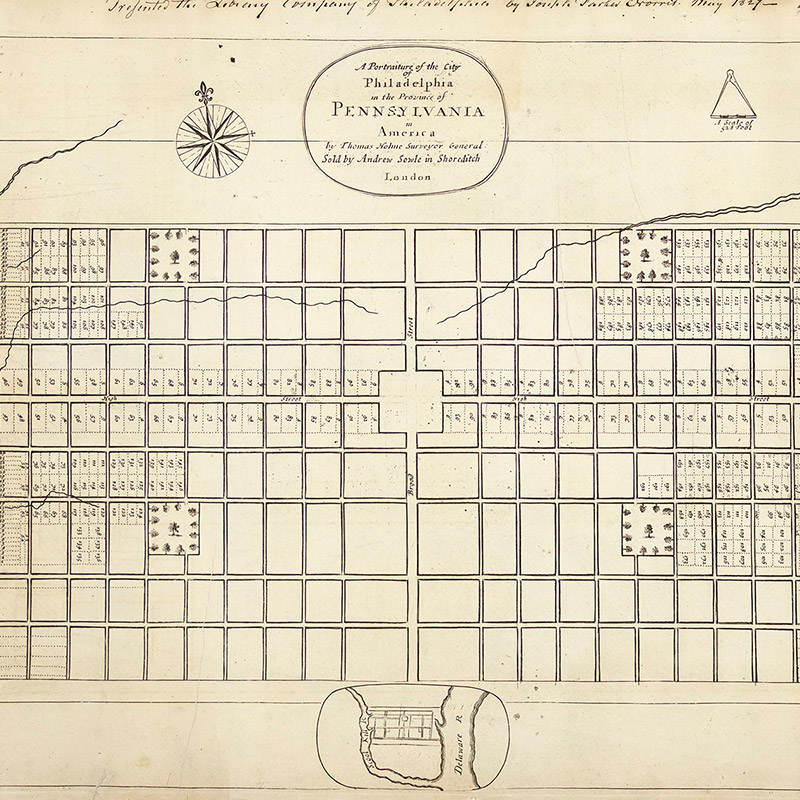

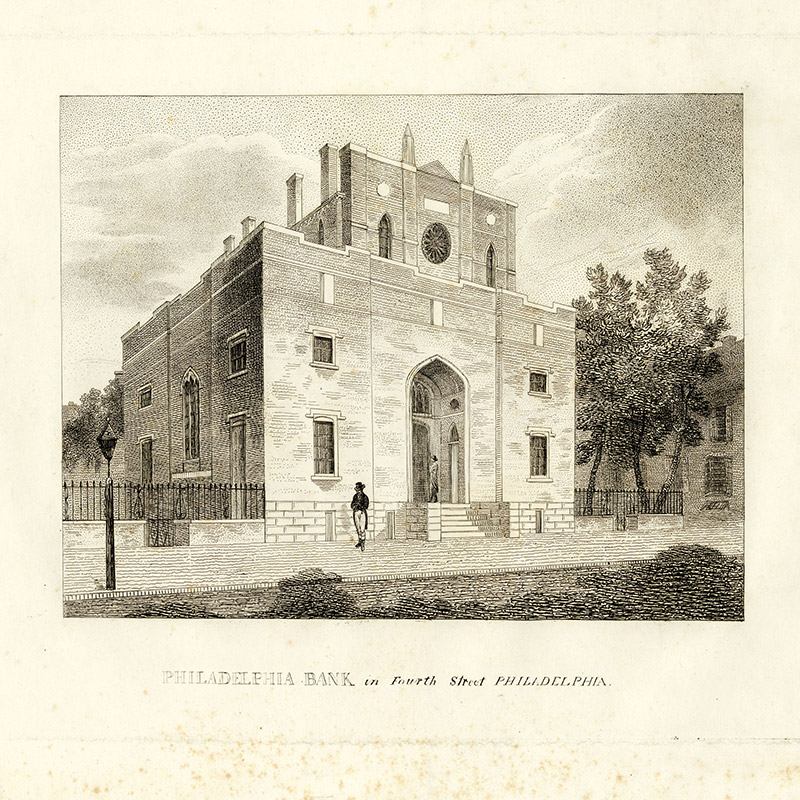

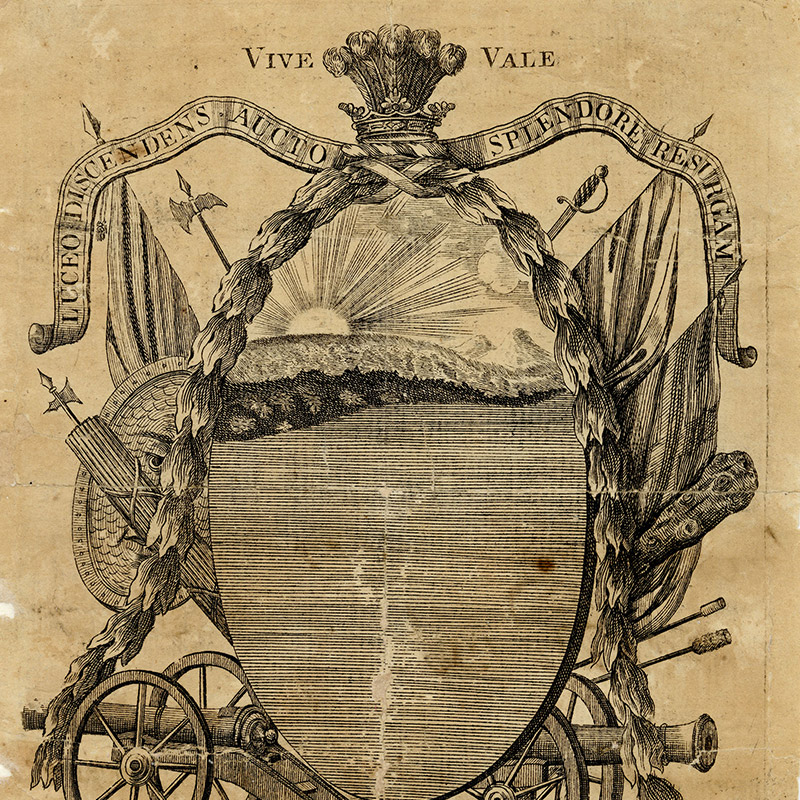

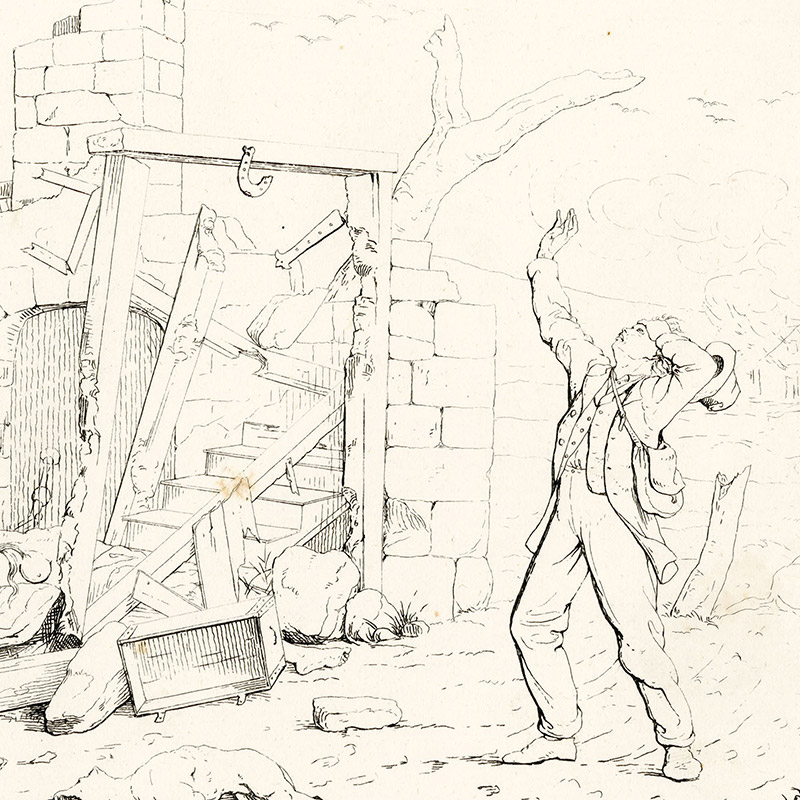

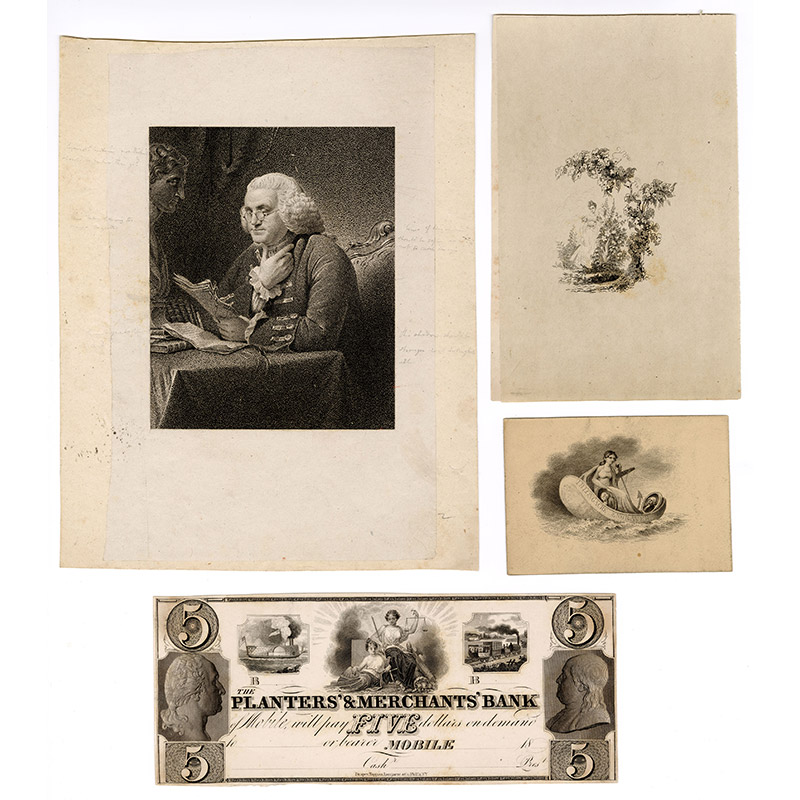

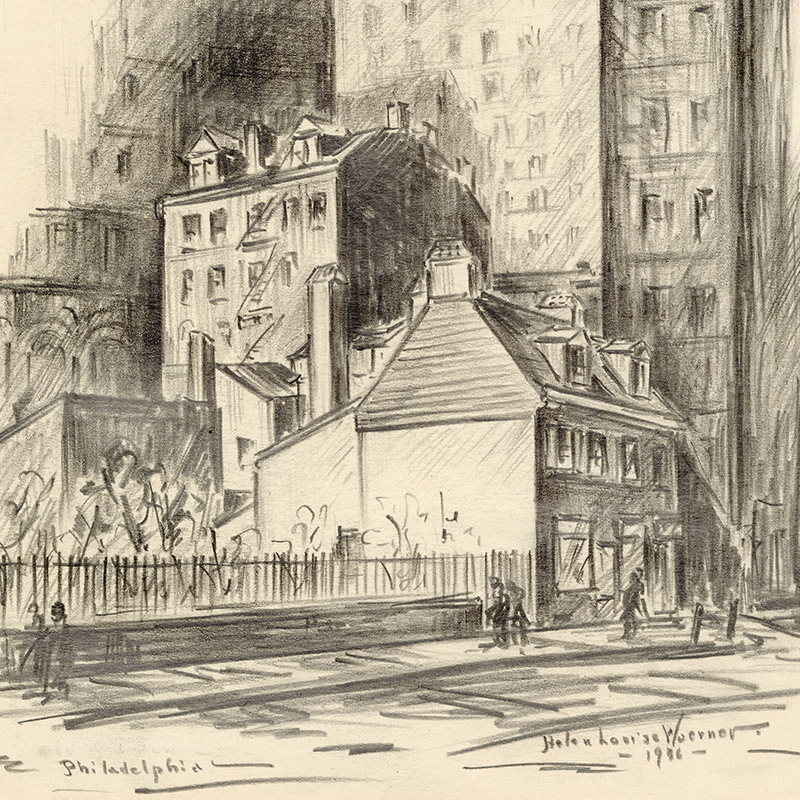

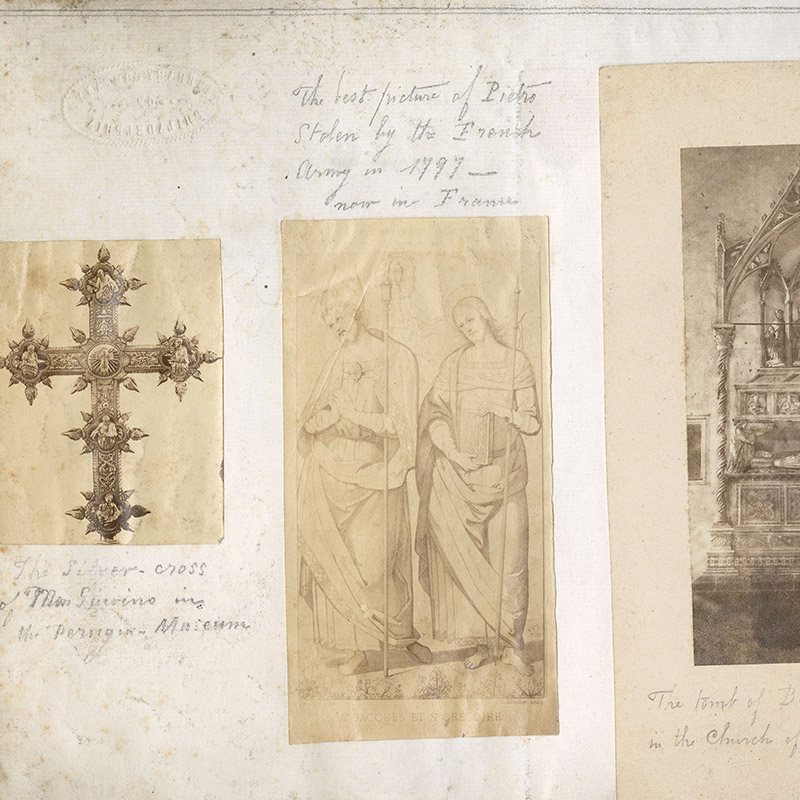

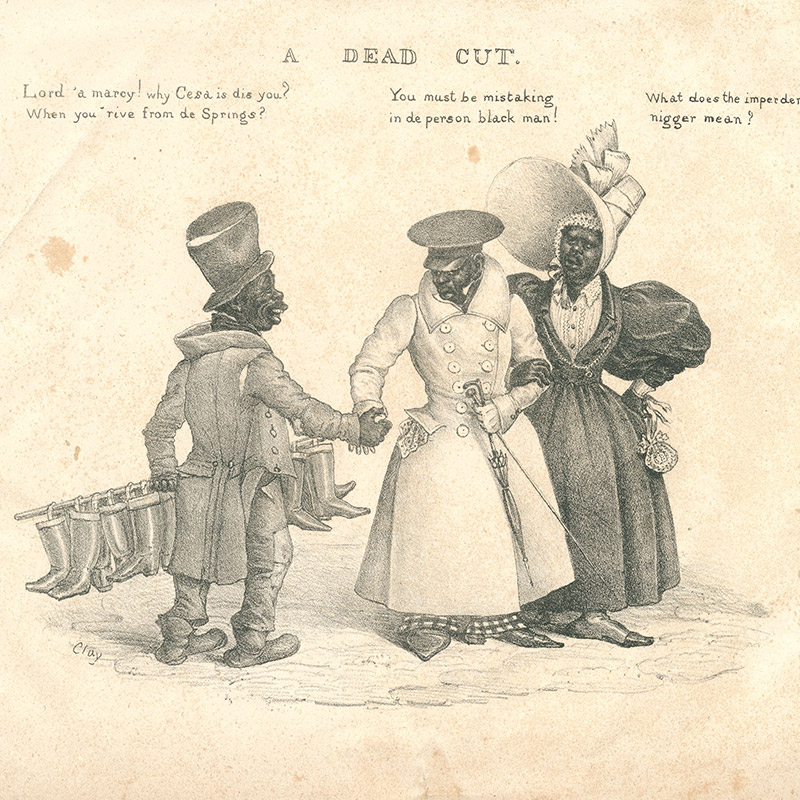

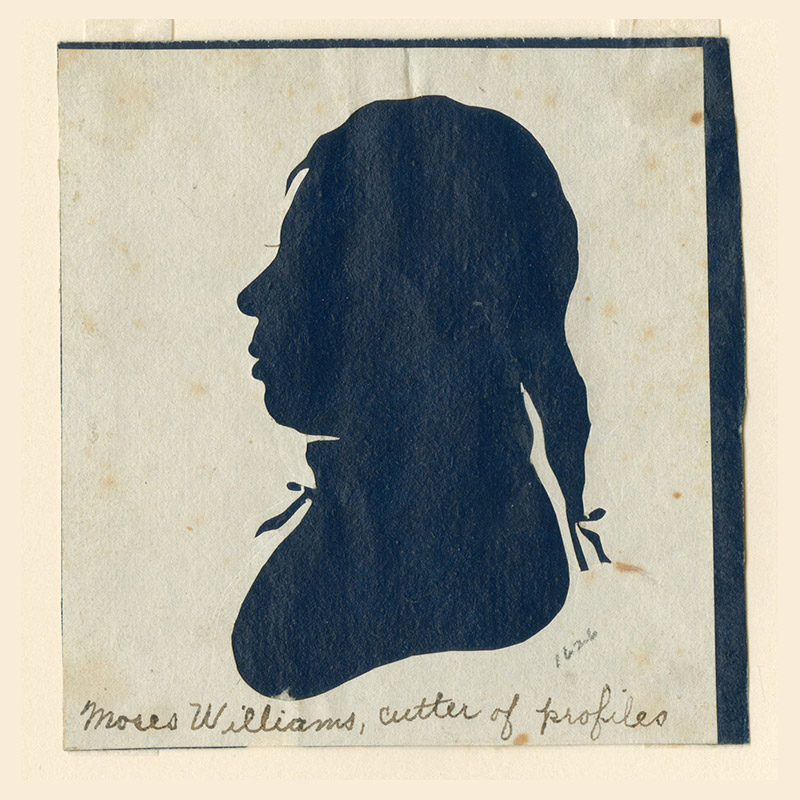

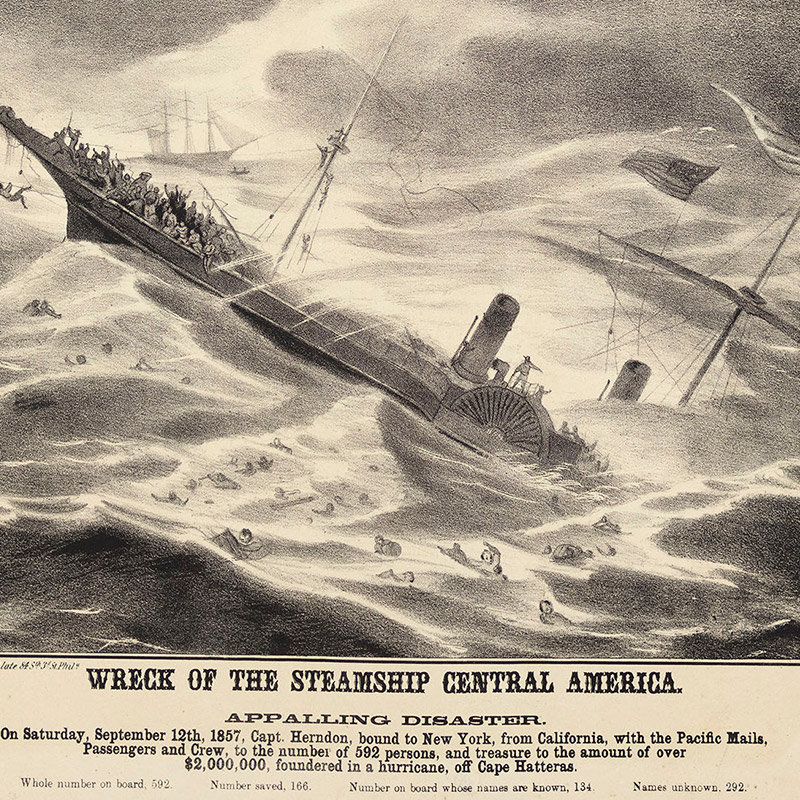

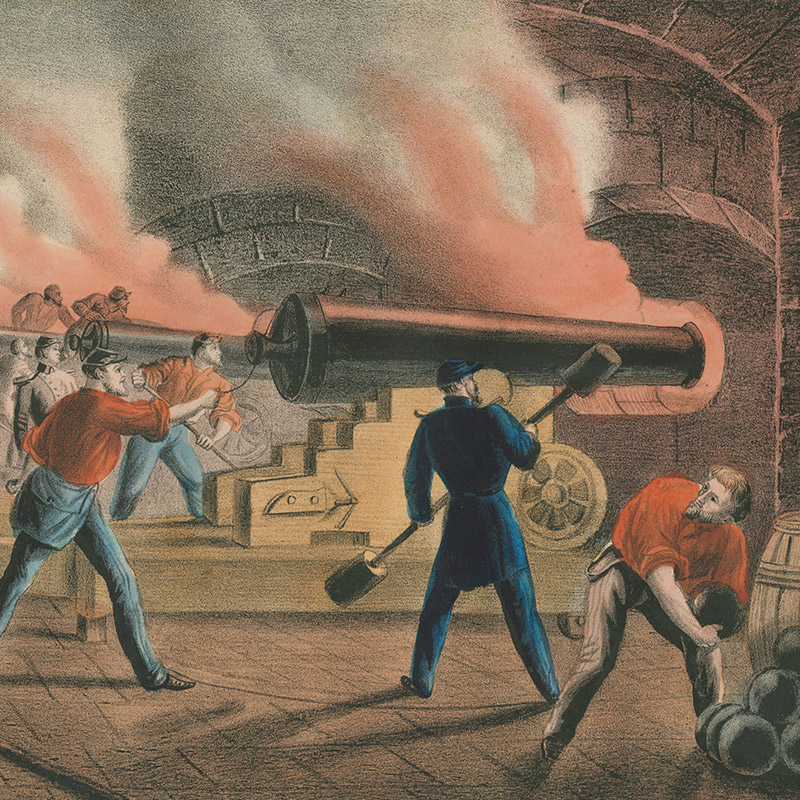

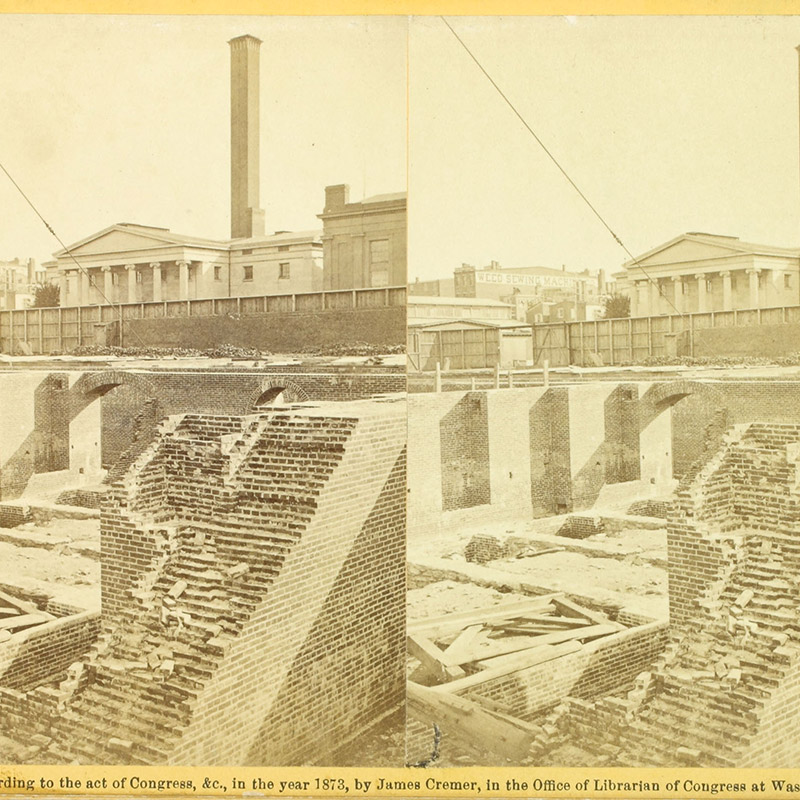

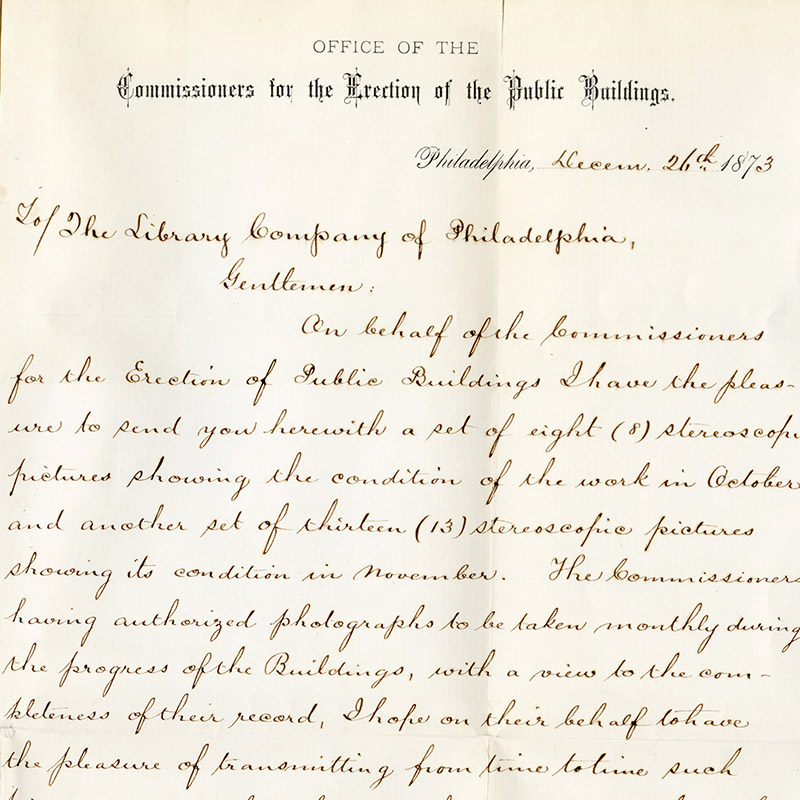

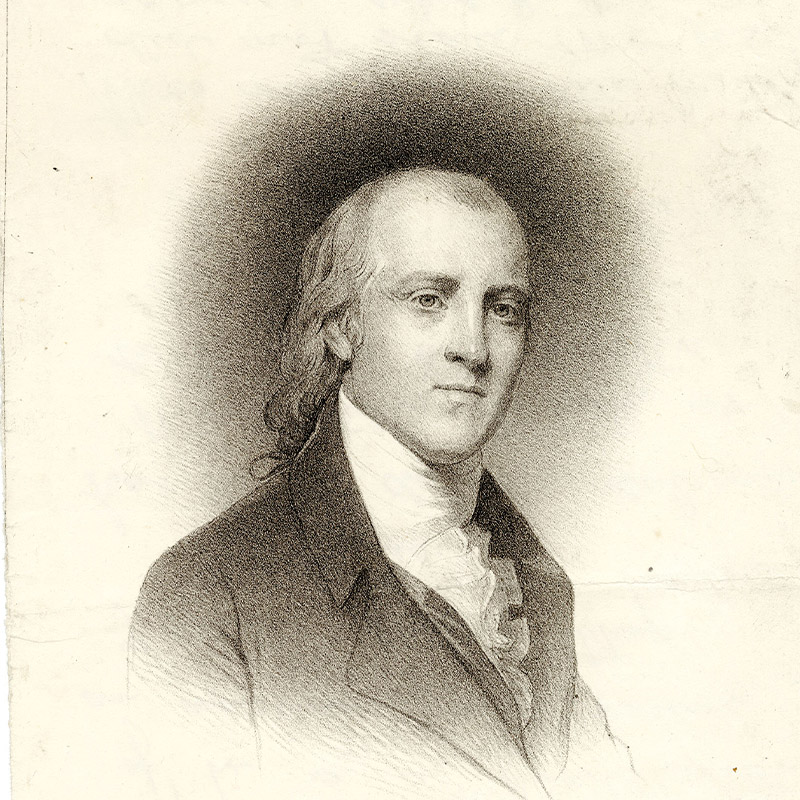

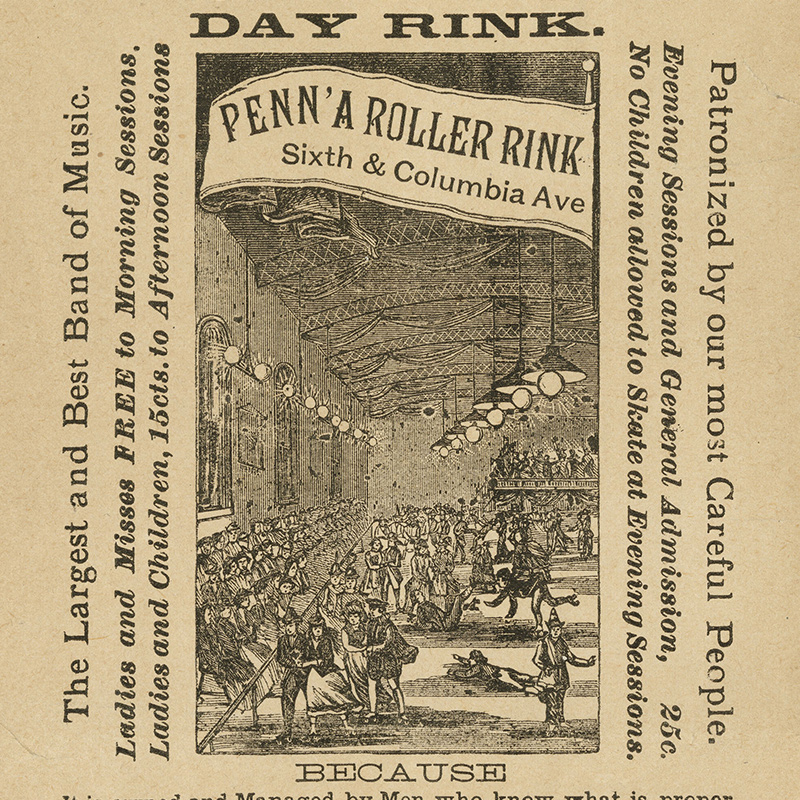

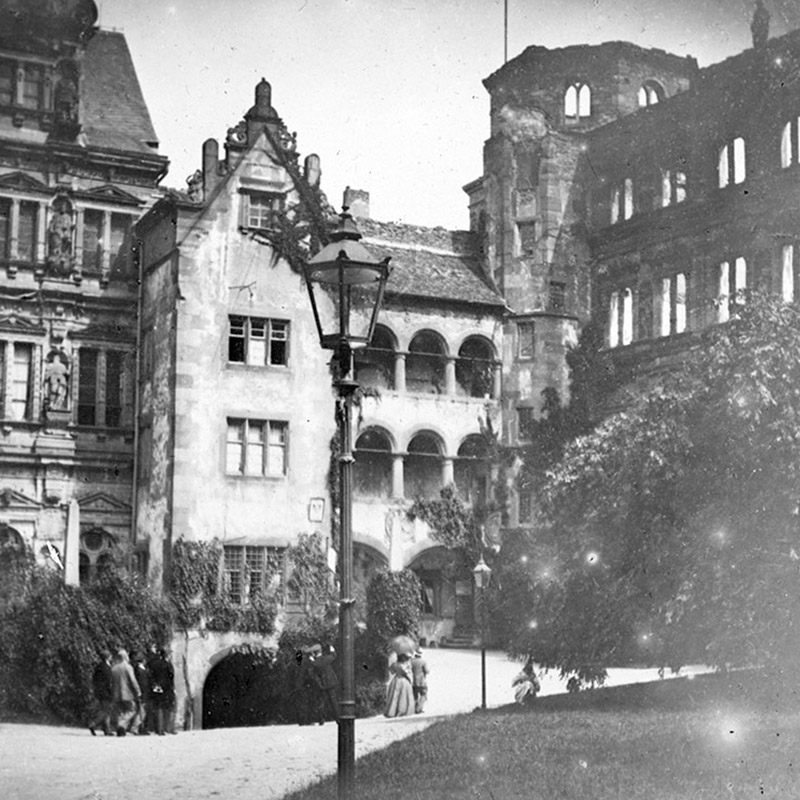

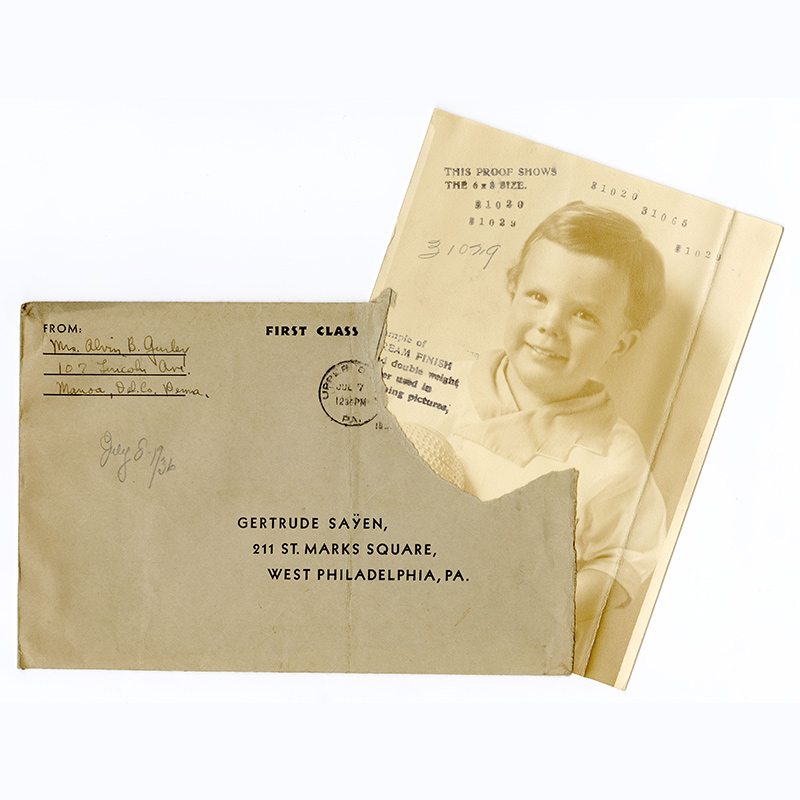

The stewardship and content of the Graphic Arts Collection at the Library Company have evolved with the institution over its nearly 300-year history. Founded as a subscription library in the 18th century, the Library Company was the largest public library in America during the 19th century. By the mid-20th century, the institution transformed into a research library. Through the 21st century, exhibitions, subject-based Academic Programs such as the Visual Culture Program, and the digital world have further influenced the growth and management of the Library and its collections. Over this time, tens of thousands of visual materials have been given, purchased, and “found” in the holdings. In response, a Graphic Arts Department was established in 1971. In fifty years, four curators have headed the Department in which they and their staffs have overseen prints, photographs, original works of art, and ephemera that were acquired before and by them. These works of popular art conceived, circulated, consumed, collected, arranged, and described over nearly three centuries are windows on the visual culture of multiple different eras. In this section, visual materials acquired before and after the establishment of the Department provide snapshots of the scope and (un)conscious biases affecting the continual evolution and historical meanings of the Graphic Arts Collection.

Items marked with an asterisk (*) appear only in the online exhibition.

Imperfect History is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, Walter J. Miller Trust, Center for American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jay Robert Stiefel and Terra Foundation for American Art.