Curatorial Space and Place

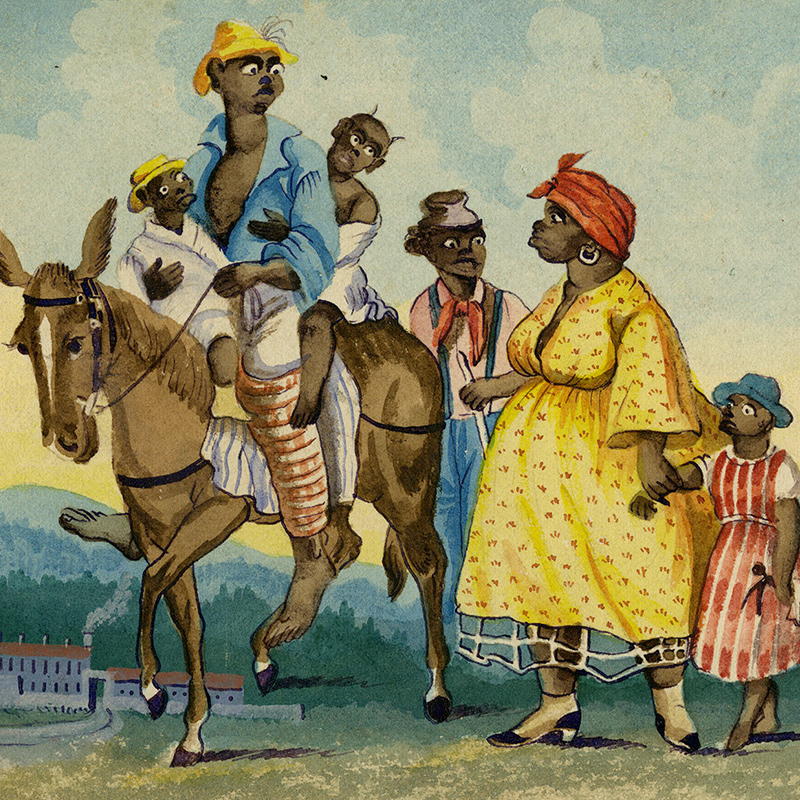

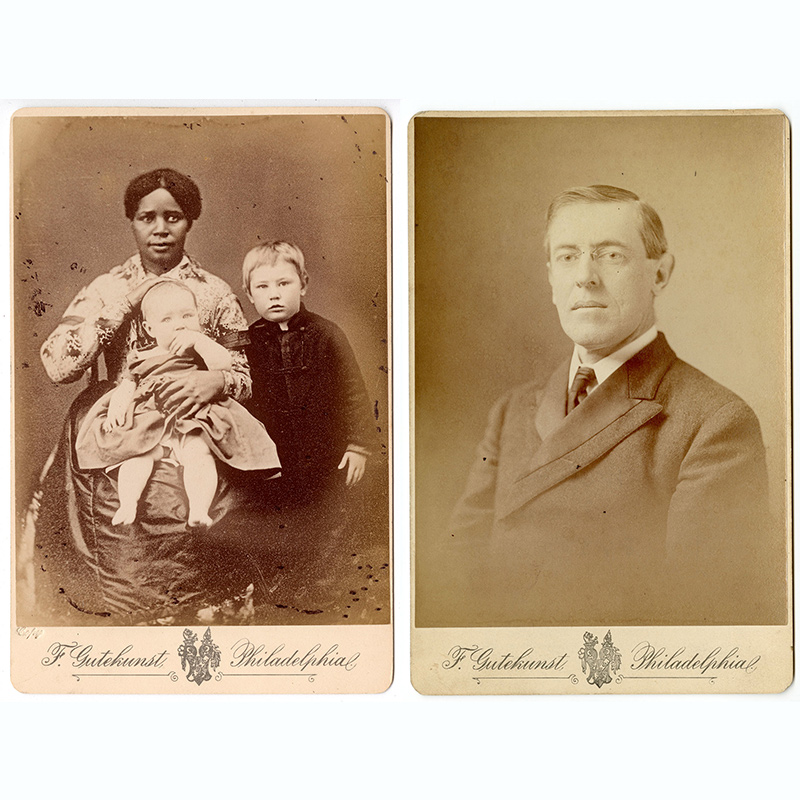

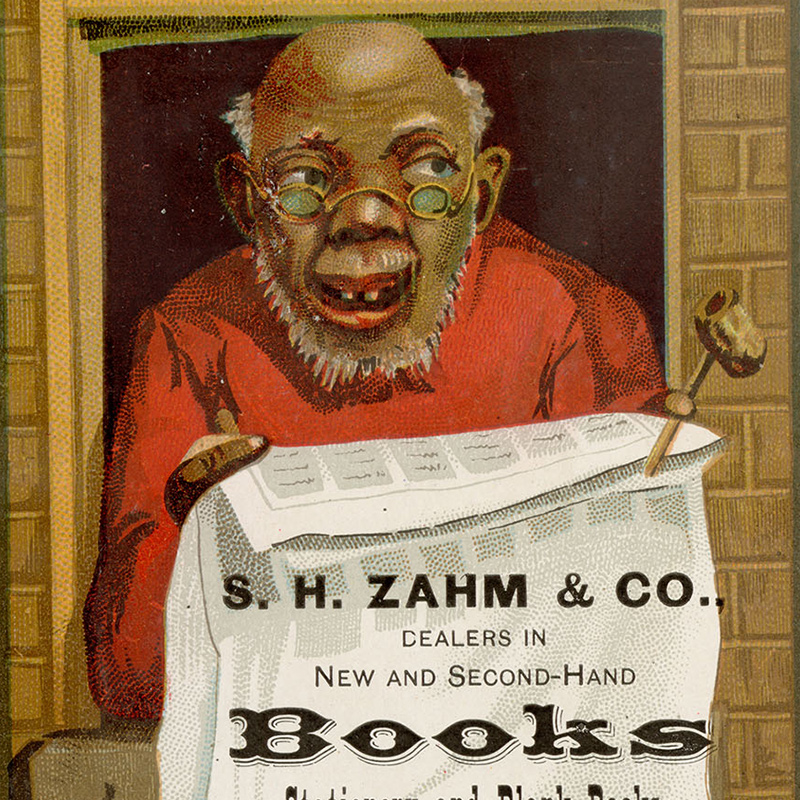

A group of newly-arrived enslaved Africans stand on an auction block on a city street, awaiting their fate. An incarcerated white man imagines an enslaved family trekking toward their freedom in the aftermath of the Emancipation Proclamation while reckoning with his own captivity. An African American woman calls out to a white photographer taking images of her home, resisting what she sees as an unwelcome encroachment into her daily life.

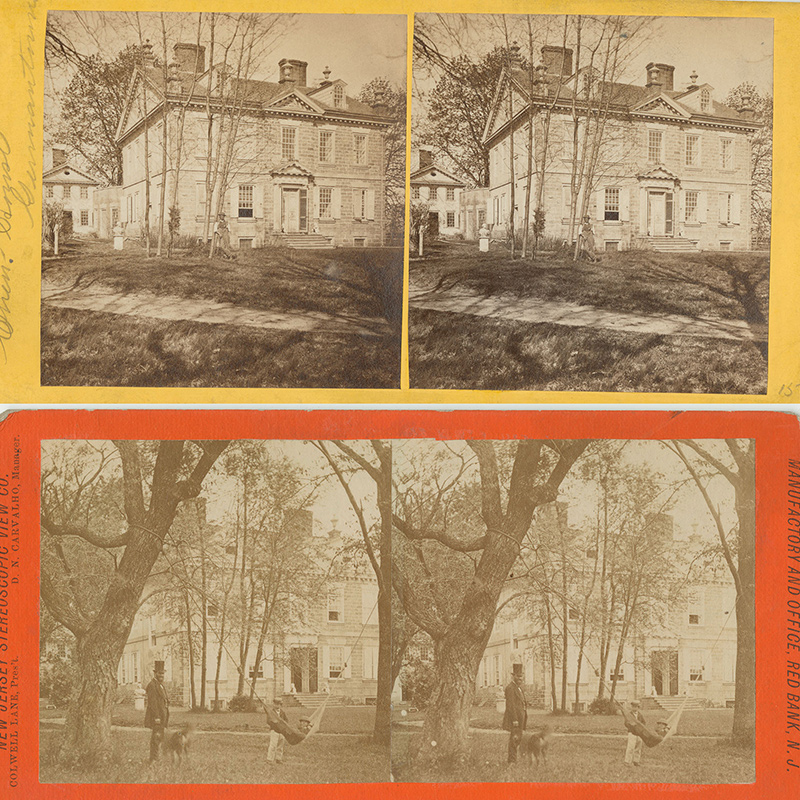

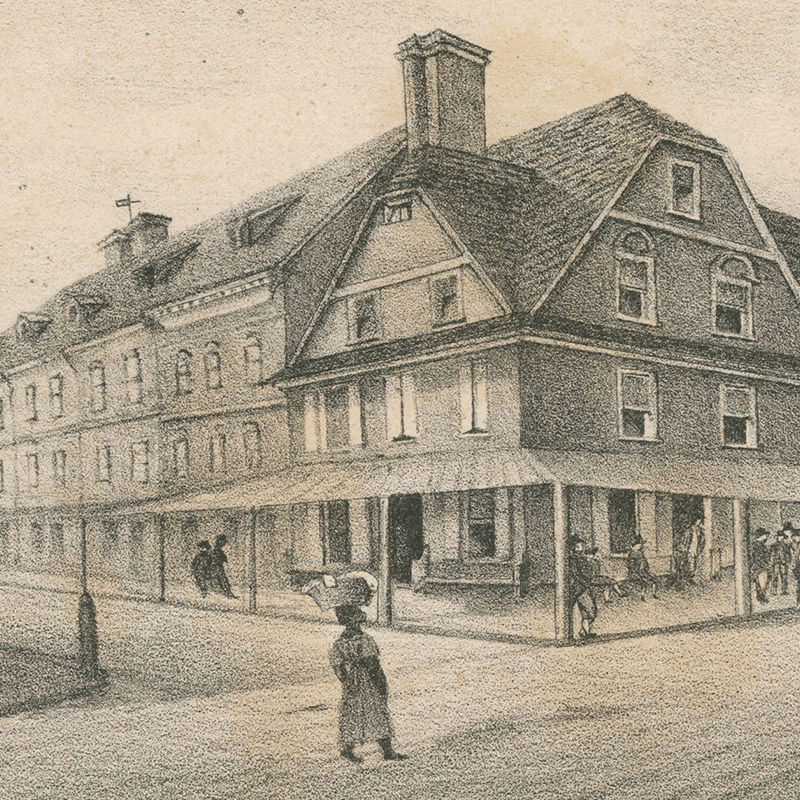

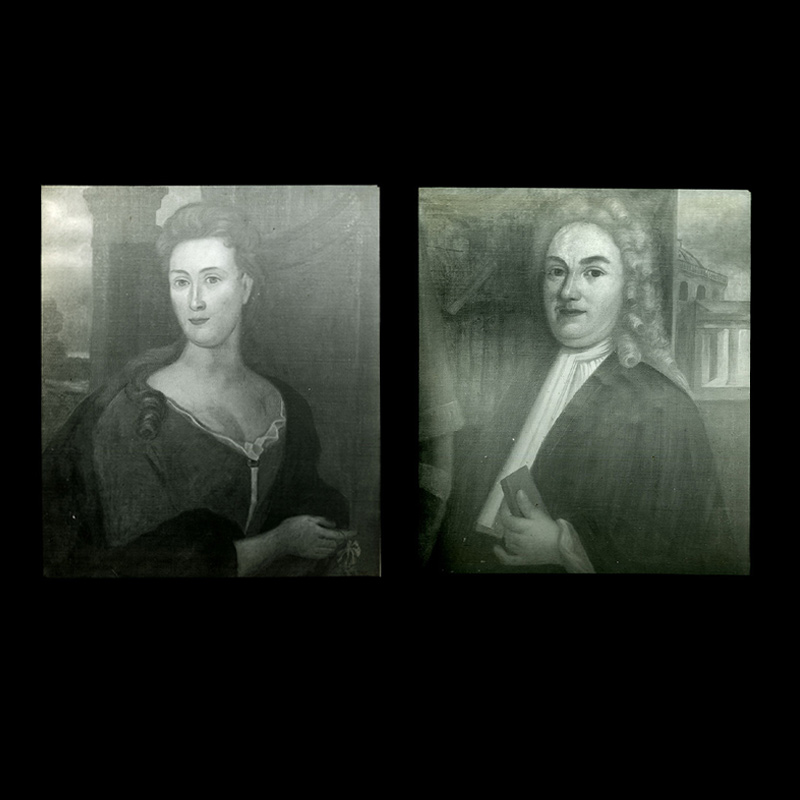

The scenes that the graphic materials in this section depict and the interpretations that they evoke are varied. When looking at them, we are prompted to consider the social conditions that structured Philadelphians’ everyday experiences of urban space. These images also reflect the perspectives of the people who made and collected them. The way that we describe and memorialize these spaces is also a fundamental piece of the historical paradigm.

Imperfect History is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, Walter J. Miller Trust, Center for American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jay Robert Stiefel and Terra Foundation for American Art.