Hassane

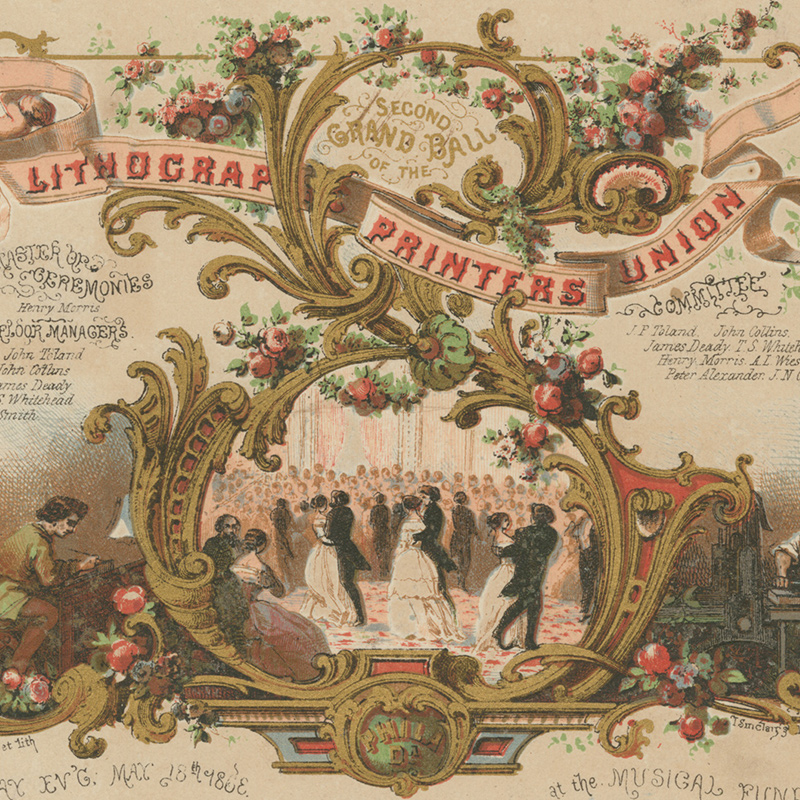

Alphonse Bigot, Second Grand Ball of the Lithographic Printers Union … (Philadelphia: T. Sinclair's Lith., 1863). Chromolithograph. Gift of Margaret Robinson, 1991.

Being an artist in the United States has long been understood as a leisurely pursuit reserved for the upper class, rather than a trade. If we expand our view of what constitutes art from work that is solely created for aesthetic purposes, we can see how the history of visual culture has intersected with the history of labor movements in the U.S. This chromolithograph, which is an advertisement for an 1863 ball held by the Lithographic Printers Union, represents the confluence of these histories. From available evidence, it seems likely that Alphonse Bigot (ca. 1828-1872 or 3), the maker of this trade card, was part of the organization. At the same time that this card breaks down the boundaries between art and craft, it also begs the question of whether non-white lithographers, like Patrick Reason (1816-1898) of New York, were also members of such trade unions. The exclusion of Black people from labor movements is yet another gap made visible by this object.

Piola

Alphonse Bigot, Second Grand Ball of the Lithographic Printers Union … (Philadelphia: T. Sinclair's Lith., 1863). Chromolithograph. Gift of Margaret Robinson, 1991.

During the middle of the Civil War, the Lithographic Printers Union, instituted in 1854, held their second grand ball. On May 10th in the Sunday Dispatch, next to a list of killed and injured soldiers of the Battle of Fredericksburg, the grand affair was announced. Although the invitation shows a trade in celebration, it was not one unaffected by the war. Studios were understaffed from enlistments and commissions of work were fewer. At the same time, the Union’s members, including the artists of this invitation, produced lithographs of soldiers, battlefields, and volunteer saloons. The ball scene and work vignettes, however, do not belie the whiteness of the trade in which the men worked. Available records for the Philadelphia trade suggest that possibly one Black man, John Godber (b. ca. 1841), worked as a lithographer at this time while millions remained enslaved despite the Emancipation Proclamation.

Weatherwax

Alphonse Bigot, Second Grand Ball of the Lithographic Printers Union … (Philadelphia: T. Sinclair's Lith., 1863). Chromolithograph. Gift of Margaret Robinson, 1991.

Producing this invitation gave Philadelphia lithographer Alphonse Bigot (ca. 1828-1872 or 3) the opportunity to show off his artistic skill. He created a lively image of cherubs darting among swirling banners and curlicues and dancers moving to the sounds of an unseen orchestra, a sharp contrast to vignettes of the everyday work of a lithographic shop. Although clearly meant to demonstrate the talents of its creators, the invitation contains an imperfection—the “3” in the date is printed backwards. Established in Philadelphia in 1854, the Lithographic Printers Union opened its membership to “acknowledged practical Lithographic Printers” willing and able to pay a $3.00 (approximately $100 in 2021 currency) initiation fee and monthly dues of 20 cents. Although not explicitly stated in the constitution and by-laws, membership was most likely confined to white males.