Benjamin Franklin: Philadelphia’s First Fashionista

From a very young age, Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) understood that appearance was the basis on which people judged each other. In 1722, when he was merely a teenager, Franklin decried the “Pride of Apparel,” promoting simple, honest “homespun cloaths” instead. In his early twenties, when Franklin was trying to establish his reputation as a reliable tradesman, he knew personal style would be crucial to his success. As he later wrote in his autobiography, “I took care to not only be really industrious and frugal, but also to avoid every appearance of the contrary. I was plainly dressed.” Franklin’s deliberate self-fashioning can be seen in his various portraits. He usually dressed modestly, foregoing the powdered wigs and ruffled shirts of his peers for unstyled hair and coarse, homespun suits. Appearing before Louis XV in 1767, however, he knew his signature plain dress would not do, and called upon a tailor and a wigmaker to dress him appropriately, making him “into a Frenchman.” He exclaimed, “Only think what a Figure I make in a little Bag Wig and naked Ears!” Even as he purchased the luxury goods brought by the consumer revolution, Franklin continued to praise simple fashions and saw them as embodiments of American domestic production, independence, and self-sufficiency. Because of his ability to understand and take advantage of the prevailing fashion systems of his day, we can consider Franklin to be Philadelphia’s—and the nation’s—first true fashionista.

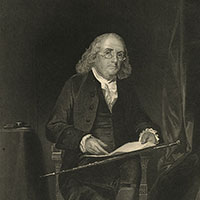

Various portraits of Benjamin Franklin, ca. late-18th-19th century.

Between the 1830s and 1850s potteries in Staffordshire, England, produced porcelain statuettes of notable figures for the domestic market. American tourists loved them so much they brought them back by the trunkful. The clothes of this Benjamin Franklin figure are decorated with bright embellishments including flowers on his vest and gold-striped breeches. This was typical of the Staffordshire style, and pleasing to 19th-century middle-class tastes. But Franklin himself never would have worn something so showy.

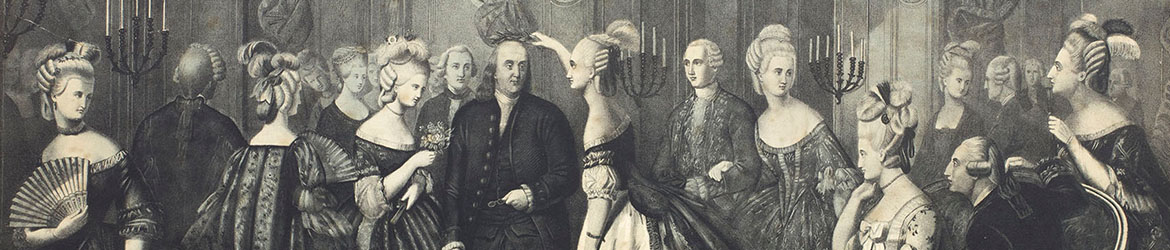

When Franklin appeared at the Court in Versailles on March 20, 1778, to sign a treaty of alliance between France and the United States, he did so as only he could—with understated panache. Amidst the Court’s most luxurious fashions, a bespectacled and wigless Franklin wore a plain dark velvet suit and his signature fur hat. His outfit was political: it symbolized the virtuous simplicity of republicanism, frontier self-sufficiency, and the integrity of the new American nation. He wrote to a friend in England: “Figure me in your mind. . . being very plainly dress’d, wearing my thin gray strait hair, that peeps out from under my only coiffeur, a fine Fur Cap, which comes down to my Forehead almost to my spectacles. Think how this must appear among the Powder’d Heads of Paris!” To one Parisian, the painter Elizabeth Vigée-Le Brun (1755-1842), Franklin looked like “a big farmer, so great was his contrast with the other diplomats, who were all powdered, in full dress, and splashed all over with gold and ribbons.” The French loved him all the more for it.