Philadelphia Street Style

Quaker Samuel Metford (1810-1896) was a prominent silhouette artist who learned the “scissors art” in America before returning to his native Britain to ply his trade as a professional “profilist.” While here, he made portraits of countless people, including this Quaker man, identifiable by his broad-brimmed hat and long simple coat; in his hands he holds an umbrella and spectacles. Silhouettes were particularly popular among elite Quakers, because they conformed aesthetically to their sensibility of economy and plainness, which came from a belief in the “inner light” and the simplicity of truth.

Over time, as they grew wealthy from global commerce, Quakers increasingly struggled to reconcile the spiritual tenets of plain dress with their worldly successes. They continued to practice plainness, but embraced garments made with more sumptuous materials and crafted of the finest workmanship.

One of the few vanities that Quakers allowed themselves was the photographic portrait. These images exemplify the definitive Quaker style: simple caps, criss-crossed neckerchiefs covering the bodice, and shawls for women; for men, black suits devoid of all ornamentation.

This address to Quaker youth warned them against becoming devoted to the “terrestrial” vanity of fashion, describing it as a “pois’nous plant.” In 1810, Quaker Margaret Hill Morris (1737?-1818) wrote to her granddaughter, “I entreat thee not to launch into extravagance in dress; it shows a weak and vain mind to be continually changing one’s dress as the fashion changes.”

Frederick Smith. On Fashion. An Address to the Youth of the Society of Friends. New York: Collins, Perkins & Co., 1805.

As more people were able to adopt fashionable dress by the second quarter of the 19th century due to the rise of cheaper, ready-made clothing, Quakers’ plain style increasingly seemed outmoded. Wealthy Philadelphian Elizabeth Willing, for one, remarked in 1824, “The Quaker style does not altogether please me”; she found it “regular” and “stiff.” This much-reprinted article from 1832 enumerates the many exceedingly fine distinctions in so-called “plain” dress, from different shades of white to the fit of custom-made gloves “only visible to the practiced eye of a Lady Friend.” Elite Quakers, it seemed, were as ostentatious in their plainness as members of Philadelphia’s high society were in their outlandish dress—itself a subject of frequent ridicule.

Quaker styles were surprisingly diverse. Some Friends wore bright colors and lush fabrics while others limited their wardrobes to certain palettes and textiles. Despite individual variations, Quaker “plain style” meant a rejection of extreme cuts, the latest stylistic fads, patterned materials, ornamental trims, and ruffles—the very features embraced by many other Philadelphians.

Here, Quakers are shown outside the “Bibliothèque de Philadelphie,” the Library Company of Philadelphia. Founded by Benjamin Franklin and a group of his friends in 1731, the Library Company occupied this building at Fifth and Library Streets from 1790 until 1880.

In this essay, influential publisher and political economist Mathew Carey (1760-1839) railed against fashion, “a most arbitrary, inexorable, and capricious tyrant.” He argued that it was wasteful and often impractical, could bankrupt families, and created “pernicious” competition. Most importantly to Carey, the drive for new fashions led to the exploitation of countless workers, as he outlined in Appeal to the Wealthy of the Land (1833), which maintained that seamstresses could not earn enough to survive, even if they worked sixteen-hour days.

Despite the critiques of Carey and others throughout the 19th century, Americans continued to embrace and celebrate the latest fashions, as the trade card, featuring elite Philadelphians strolling Fairmount Park, shows.

This caricature is one of a number of images lampooning the pretensions of “fashionable” Philadelphians. The man—with his ruffled shirt, pomaded hair, fancy watch fob, top hat, cane, monocle, and spurs (!)—is so dandified he looks like a woman. He bows to a belle who is also outrageously dressed. The weight of her oversized bonnet nearly cripples her, and the short length of her dress causes her to remark, “It is rather Cold, Sir!” Even the children and young women are dressed ridiculously, in disfiguring high-waisted dresses, and bonnets that act like blinders.

As odd as it may seem, Philadelphia’s underworld also influenced the city’s fashion regime. Gang members made a practice of dressing ostentatiously both as a way of differentiating themselves from rival groups and to flaunt their ill-gotten gains. The Killers was a group organized in about 1846. Associated with the Moyamensing Hose Company and the Democratic Keystone Club, they were menaces to the neighborhood, albeit well-dressed ones. Two of their members are shown here loitering, dressed in plaid wool pants, long-tailed coats, loosely-tied cravats, and bling.

Journalist George Foster observed, “These harem-scarum fellows go to the Wissahiccon [sic] simply because they must have somewhere to go and show off their flashing rings and guard-chains, their fine clothes and rowdy sweethearts.”

Despite the many contributions of Philadelphia’s free blacks to the city’s political, social, cultural, and religious life, critics feared they would upset existing racial hierarchies by acting and dressing like whites. This political cartoon shows a stylishly-dressed couple, possibly prominent Philadelphians Elizabeth Willson Hinton and Frederick Augustus Hinton. She wears a fancy bonnet, custom-made dress, and fine jewelry, and carries a parasol and a lace handkerchief. He is clad in a ruffled shirt, top hat, and vest. In one hand he holds a monocle attached to a very long chain, and in the other, a cane. They remark that a “white loafer” is looking at them and surmise that he is probably from New York, where genteel African Americans were unusual sights.

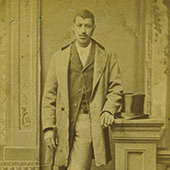

The largest and most prosperous population of free African Americans in the 19th century lived in Philadelphia. They contributed to the city’s political, social, educational, cultural, and religious life. Like other members of the middle and upper classes, free blacks were fashion-conscious. Taking advantage of the emerging visual technologies, they often sat for portraits at the growing number of photography studios.

In the ambrotype, a young Cordelia Sanders—of Philadelphia’s prominent Stevens-Cogdell/Sanders-Venning family—boldly faces the camera wearing a finely-tailored dress and cameo brooch. The photo of the men in straw hats was likely taken on a summer excursion to Pleasantville or Atlantic City and shows them posed, playfully, with money and cigars. In the unidentified portrait, a man appears with all the markers of gentility, including his top hat (possibly made by Stetson), a cane, and his dog.

Unlike the idle wealthy and non-manual laborers like clerks and merchants, whose clothes were close-fitting and made of the best fabrics, workers’ outfits were practical: “stout” and water-proof boots, skirts of adjustable length, aprons with pockets, and sleeves and cuffs that could be fastened tightly.

The sturdy cloth used to make the outfits shown here could very well have been woven at the mills in Manayunk. The children’s book City Characters makes a point of describing the laundress’s “tedious and disheartening” work of washing and ironing rich people’s clothes, which, unlike her own, required great care. Having “just finished a hard day’s work,” she carries a full basket of clean clothes to their owners.

This satire, written from the perspective of a traveler new to the city, lampoons the pretensions of elite Philadelphia society. The plate, “The walk in Chestnut Street,” shows dandies in their wide trousers and complicated jackets strutting alongside women whose bonnets are so big they conceal their faces. The book was written by Robert Waln, Jr. (1794-1825), the son of a prominent Philadelphia Quaker merchant.

“Promenading”—strolling in public, to see and be seen, often in search of a mate—was all the rage in the early 19th century. Chestnut Street, a “grand and ceaseless thoroughfare,” with its “cumbrous heaps of the richest merchandise,” was a perfect place to do it. Women wore showy dresses just for the purpose, and were advised on the proper etiquette to look their best.

“Promenading,” in Etiquette for Ladies. Philadelphia: G.B. Zieber & Co., 1845.

Affirming Philadelphia’s status as America’s most fashion-forward city, the editors of Godey’s Lady’s Book began offering in the late 1850s a shopping service. Readers living far away but desirous of the most up-to-date styles could send money and a list of what they wanted, and Godey’s staff would make purchases at local stores. Many of Godey’s suppliers, such as jewelers Abijah Warden and J.E. Caldwell, and clothiers Evans & Co. and L.J. Levy, were located along Chestnut Street.

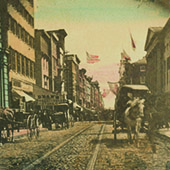

By the end of the 19th century the once lovely Chestnut Street near Independence Hall had begun to grow shabby as upscale shopping venues moved westward with the city’s continued expansion. But as these stereographs show, Chestnut Street was still a vibrant place with pedestrians vying for space with horse-drawn carriages and street cars, inspiring the strikingly obvious title for one image: “Chestnut Street Crowded.”

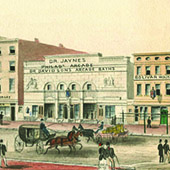

Built in 1826-1827 and designed by John Haviland after a Greek temple, the Philadelphia Arcade was once the anchor of Chestnut Street and responsible in large part for attracting new businesses and people to the area. The open galleries of the lower floors housed stores such as Joseph Moore’s fancy and dry goods shop, the third floor was occupied by Peale’s Museum, and the basement contained a restaurant. A few years after Henry Tanner included the building in his Stranger’s Guide, journalist George Foster praised the many “splendid buildings” recently erected in Chestnut Street, “upon the sites of old and crumbling rat-traps.” It was demolished between 1859 and 1860.

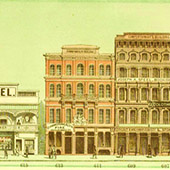

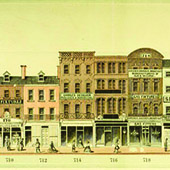

Commissioned by antiquarian Ferdinand Dreer (1812-1902), these nostalgic views show Chestnut Street bustling with well-appointed people strolling the sidewalks and riding the omnibuses. During a leisurely outing they could purchase fancy trims at Horstmann’s, a fashion plate at Mahan’s, boots at Benkert’s, elixirs at Schenck’s, and books at Hooker’s. When taking a break from shopping, they could visit the spa in the Arcade, have a bite to eat at the Columbia House Hotel, or take in a show at the Chestnut Street Theater.

These sweeping views of Chestnut Street, from De Witt Clinton Baxter’s (1829-1881) Panoramic Business Directory of Philadelphia for 1859, suggest the area’s robust commercial activity on the eve of the Civil War. Advertisements below the streetscapes promote many style-related establishments, from cloak makers and tailors to photographers and opticians. Many, such as Stokes’ Temple of Fashion, Rockhill & Wilson, and McAllister & Bro., are featured elsewhere in the exhibition.

In 1861 Baxter organized and led the 72nd Pennsylvania Volunteers, better known as “Baxter’s Fire Zouaves”—a brigade comprised mostly of men from Philadelphia fire companies known for their flashy uniforms and precision drills, which they demonstrated to the public on the stage of the Academy of Music.