Fashion Makers

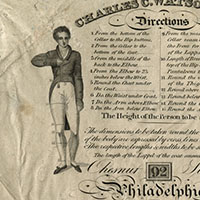

Until the late 18th century, most people wore clothes that were once someone else’s, exchanged among and adapted by family members over generations. By the dawn of the 19th century, rising numbers of tailors were making clothes to order. Because a good fit was key, many tailors devised their own systems for customers to measure themselves, and for other tailors to create patterns if they knew how to sew but not design. Samuel A. and Asahel F. Ward, tailor Allen Ward’s sons, played an important role in the rise of ready-made fashions, promoting their patterns through publications and brightly-printed fashion plates. They followed Parisian styles, but adapted them to suit Philadelphia tastes.

S.A. & A.F. Ward. The Philadelphia Fashions & Tailors’ Archetypes. [Philadelphia, 1849].

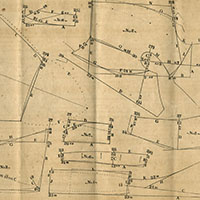

During the antebellum years, men and boys were increasingly able to purchase ready-made clothes—that is, garments patterned and constructed based on standard sizes—rather than going to the tailor for a custom-made outfit. To compete with higher-end establishments, businesses like Rockhill & Wilson had all the necessary amenities, including good lighting, mirrors, dressing rooms, spittoons, and industrious tailors (seen in the back) who did alterations. In the foreground, a dandified clerk attends to a mother and her son, while other customers examine garments and get fashion consultations. Although it opened during the economically calamitous year of the Panic of 1857, the store stayed in business until 1882.

Although Philadelphia’s textile trade long resisted industrialization, by the 1820s, manufacturers began rapidly adopting large-scale mechanized production, establishing textile mills along a recently completed section of the Schuylkill Navigation Company canal, in the new village of Manayunk. In less than a decade, the area surpassed its rival Pawtucket, Rhode Island, in both number of workers and spindles, earning it the title “The Manchester of America.”

Joseph Ripka (ca. 1789-1864), a weaver by training, immigrated to Philadelphia in 1815 and established a small handloom shop in Kensington. In 1828 he invested in a cotton mill in Manayunk to make heavier cottons for cheap men’s dress and the durable clothing worn by laborers and slaves. By 1832, Ripka was employing some 300 people who worked over 7,000 spindles and over 200 power looms. By the end of the decade he owned four mills and oversaw one of the largest and most successful textile operations in the country. A street bearing his name still runs through Manayunk.

By the 1840s, entrepreneurial tailors were not simply making clothes but pursuing related business ventures. The Wards—Allen and his sons Samuel (ca. 1813-1877?) and Asahel (ca. 1817-1895), whose work can be seen elsewhere in the exhibition, sold tape measures, tailors’ crayons, shears, trimmers, patterns, patented protractors, and other tools to “take the measure of a man.” Their fiercest rival was Francis Mahan (ca. 1790-1871). For years, Allen Ward and Francis Mahan publicly accused the other of stealing his tailoring systems, and Mahan brought a libel suit against Ward in 1840.

Some tailors also became publishers, commissioning seasonal “fashion plates.” Other tailoring shops would purchase these posters for about a dollar and hang them in their windows to show that they could provide garments in the latest styles. The Wards benefitted from having a long-standing relationship with Matthias Weaver, one of the city’s most proficient lithographers; in at least one instance, they paid him for his services with a new suit.

The plates here, representing the work of the Wards and Mahan, show people engaged in various genteel leisure activities, such as playing the piano, riding horses, and hunting against a backdrop that resembles the landscape of Manayunk’s mills. The image on the right, produced during the Civil War, places Union generals Henry Morris Naglee and Nathaniel P. Banks in the foreground, with soldiers’ tents behind them.

Straw hats were made by braiding thin strips of straw together and weaving, coiling, and sewing the resulting strands into different shapes. This labor-intensive handwork was performed chiefly by women, and before the Civil War, Philadelphia was one of the main suppliers of straw hats in the country, shipping them to southern markets by the gross.

This trade card shows three different styles of straw hats, decorated with embellishments that could have been imported from Europe or made in the city’s many home “factories.” They were popular summer wear, even for women: Sallie Venning Holden (1872-1959), a member of the prominent Philadelphia Sanders-Venning family, was wearing one when she sat for this photograph on a trip to Atlantic City.

Essential fashion accessories, women’s hats expressed personal taste and economic status. Milliners made and trimmed hats in a variety of materials, including straw, silk, and felt. In addition to hats, milliners also provided dresses “in a style of perfection.” Many were trained in Paris and promised their customers items made in the very latest styles. At a time when women’s clothes still resisted mass production since articles were difficult to construct and changed in style more rapidly than men’s suits, most women still made their own outfits. Only the very rich could afford the milliner’s expert design and sewing skills.

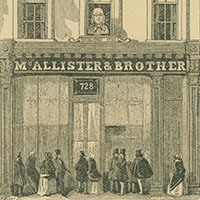

From the late 18th through the 19th century, three generations of Philadelphia McAllisters provided Americans around the country with spectacles and optical instruments. Patriarch John McAllister even made a pair of glasses with dime-sized lenses for Thomas Jefferson, according to the president’s own specifications. The oval pair here, with adjustable temples, closely resembles those worn by Benjamin Franklin in many of his portraits, and seen on his bust in the second floor of the McAllister storefront. The “D-horseshoe” glasses have tinted lenses to protect the wearer against the sun.

Tailors created patterns and cut cloth for men’s clothing. Before the invention of the sewing machine, putting the pieces together was work performed by seamstresses, one of the most exploited groups of laborers. By one calculation, it took 20,620 stitches to make a plain shirt, or about 10 hours (at 35 stitches per minute). Making a meager twelve and a half cents for each shirt and working sixteen-hour days, seamstresses could barely survive, as Mathew Carey (1760-1839) argued in this pamphlet. Born in Ireland, Carey made his home in Philadelphia and was perhaps the city’s most influential political economist, in addition to being a successful publisher.

Like similar organizations in other cities, the Philadelphia Tailoress Company tried to alleviate seamstress’ exploitation by providing financial support and establishing an independently-run shop to sell the clothes they made. It apparently did not last more than six months.

Mary Binder’s Temple of Fashion offered what shoppers on Chestnut Street had come to expect, including imported patterns in “the most approved styles,” and “all the latest novelties in Paris, London, and New York Fashions.”

Even after the advent of clothing depots offering ready-made garments at cheaper prices, there was still a robust trade in second-hand clothes. In order to save money, consumers—even the well-off—frequently had their clothes redyed, repaired, and remade into more fashionable articles. All of these processes required the efforts of skilled tailors, menders, and cleaners.

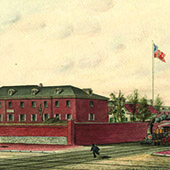

The Schuylkill Arsenal at 2620 Grays Ferry Avenue was built in 1799 to manufacture supplies for the U.S. military. By the Civil War the Arsenal moved away from munitions to provide, chiefly, clothing, tents, blankets, and the like for the Quartermaster Department through its Office of Clothing and Equipage. Items were produced through both contracting and piecework systems, the latter drawing on the city’s thousands of impoverished seamstresses (many of them soldiers’ widows), who made high-quality goods but worked for meager wages.

Over the duration of the War, the Arsenal produced about $350 million worth of clothing and equipage, twice as much as the Union Army spent on weapons. Although at its height of production the Arsenal employed some 5,000 people, it was not enough to keep up with demand: each soldier was required to have two caps, one hat, two coats, three shirts, three pairs each of trousers and drawers, four pairs each of stockings and shoes, plus an overcoat. Additional clothing depots were established in New York, Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Louisville, making uniforms from patterns and material supplied by Philadelphia.

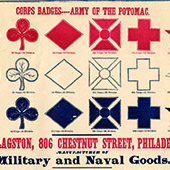

Soldiers were ever-present in Philadelphia during the Civil War. By some estimates, 100,000 Philadelphians volunteered, comprising, in whole or part, over fifty regiments. The city also served as a transfer point for soldiers traveling by train from New England to points south. And countless soldiers came here to recuperate in the city’s many hospitals. Shop owners like H.G. Clagston capitalized on soldiers’ business during the War, offering the latest badges and “Great Bargains in Presentation Swords.”

Civilian clothing styles often followed military fashions, and this was especially evident with the “Zouave craze” during the Civil War. Taking their fashion cues from French Foreign Legion units, who were considered dashing and brave, the Zouaves were by far the most flamboyant Union soldiers, sporting embroidered vests, baggy trousers, wide sashes, and decorative tassels attached to turbans or hats. Although their bright uniforms made them easy targets in the field, soldiers continued to form Zouave companies throughout the War.

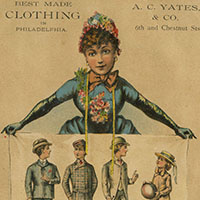

Capturing the popular imagination, Zouave uniforms also inspired women’s and children’s fashions, as seen in the images here. The Zouave jacket quickly became a women’s fashion staple: everyone had to have one. Bolero-like and designed with flared sleeves and braided trim, the jackets were restyled over time, keeping up with the changes in the styles of the Zouave uniforms themselves.

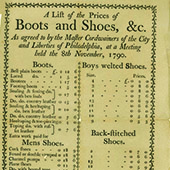

By the 1770s, Philadelphia was a major producer of boots and shoes. Journeymen performed most of the work, while master cordwainers sold the shoes and reaped the profits. Pressing their advantage, master cordwainers banded together in 1789 to control how boots and shoes were priced and advertised. Frustrated after years of seeing only modest wage increases, the journeymen struck in 1805. The leaders of the strike were tried the next year for conspiracy and convicted. Among other things, the defense argued that the master craftsmen remained a powerful union that had not disbanded on July 12, 1790, as they had claimed, and used this price list, issued on November 8th, as evidence.

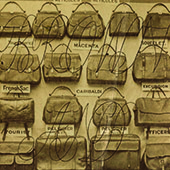

At the time Thomas Mattson put out this advertisement, Philadelphia was supporting ten tanneries on the banks of the Schuylkill River, which together processed some 40,000 cow hides, worth about $2 million, annually. Ready access to well-tanned leather in a variety of thicknesses enabled the city to become a leader in the manufacture of harnesses, saddles, whips, industrial belting, and trunks such as the ones made especially for the Stetson hat.

Ready access to a variety of leathers processed in the city’s many tanneries along the Schuylkill River enabled companies like Brown & Magee to offer a wide range of products, including trunks made of thicker, more durable “sole” leather and finer valises made of morocco (goat hide). Philadelphia was, in fact, a preeminent processor of goat hide. In 1867 alone, 1.5 million goat hides came through the city and, once processed, were used by bookbinders, shoemakers, and other manufacturers both here and abroad.

This cordwainer posed proudly with a shoe-making tool in his hand and a boot at his side.

Founded in Philadelphia in 1869, Laird, Schober & Co. was recognized around the world as a maker of high-quality shoes. The company won a grand prize at the 1900 Paris Exposition, and supplied merchants throughout the country. A label inside this pair — size 4½ B! — reads “Designed Exclusively for the White House,” a leading upscale department store in San Francisco, modeled on Paris’s Bon Marché. In 1939, the company worked with fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli to create a pair of black silk high-heeled boots with stitching shaped like toes, a design inspired by the Dadaist artist Man Ray.

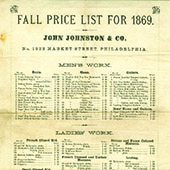

Throughout the 19th century Philadelphia was known for making high-quality shoes, crafted in small shops and fashioned of delicate materials and fine leathers, like the models listed here. The city also supported the manufacture of “common, cheap, pegged-work” varieties purchased by laborers. The city’s chief shoe-making rival, Lynn, Massachusetts, produced more pairs, but Philadelphia’s output was worth more, estimated at $15 million when this price list was printed. The city became so synonymous with the industry that ads for “Philadelphia shoes” appeared across the country.

An expert silk weaver when he entered the country from Cassel, Germany in 1816, William H. Horstmann (1785-1850) was the first person in the United States to use a Jacquard loom to weave patterns into fabrics, and was also the first to introduce braiding machines. His business was so successful that it required a more spacious factory, and in 1852 he erected a five-story building on the northeast corner of 5th and Cherry Streets. Built in a residential neighborhood, it was described as “the first manufacturing structure of elegance” in the city, and one of the first to use ornamental brickwork.

Wm. Horstmann & Sons. Ribbon sample book. [Philadelphia, 1850-1872]. Courtesy of The Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Although making ribbons and trims (passementier) was Horstmann’s core business the company expanded into related lines, such as pompons, epaulettes, hatbands, and other military goods — even buttons and swords. Extremely patriotic, the elder Horstmann worked with the War Department during Andrew Jackson’s administration to redesign soldiers’ uniforms, and raised and supported his own regiment during the Mexican War.

As odd as it might seem, the umbrella was the quintessential Philadelphia-made fashion accessory, embodying the city’s remarkable ingenuity. As one writer noted in the late 1860s:

“The sticks and metal mountings made in Frankford. . . are unsurpassed for excellence and efficiency. The stretchers, made from the best Pennsylvania Iron—the wire, drawn at Easton, and formed, forked, and japanned at the House of Refuge. . . are tougher. . . than any in the world. The mechanical genius of the manufacturers has also been active, and a number of very important improvements, which facilitate the manufacture, have originated here. . . . The Ivory and Bone Turners and Carvers, perform their part ornamenting the handles. . . and their carved Ivory-work successfully rivals the finest of England and France.”

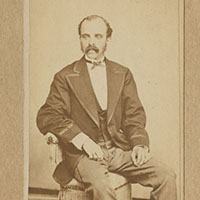

Keeping up with the latest styles, including in coiffures, became increasingly important, especially for people getting their portraits taken at the numerous daguerreotype studios operating in the city. In 1848, young bachelor Algernon Sidney Roberts (1828-1868) wrote in his diary that he paid twenty-five cents to get his hair done the day before this image was taken. He did not go to his usual hair dresser, African-American John Chew (ca. 1821-1870), however. Instead, he went to “The Frenchman,” who did his hair up in an oiled curl swept high on his forehead. Although this was quite in fashion, Roberts was dissatisfied with his look.

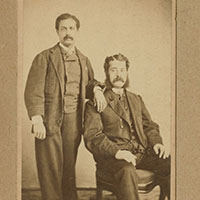

Throughout the 19th century and especially before the Civil War, barbering was a profession of high status and skill, and was a way for many of Philadelphia’s free blacks, in particular, to ascend into the middle and upper classes of the African American community. The men in these portraits include James Keith (1837-1888) and Cheslea Bass (ca. 1832-1904) (shown with Andrew F. Stevens, whose hair he very well could have styled). Bass came from a prominent family of hair dressers, and, with Keith, established a long-lasting and highly respected partnership in the city.

Portraits of James Keith, Cheslea Bass, and Andrew F. Stevens. [Philadelphia?, ca. 1865-1885]. Albumen photographs.

Dressed in a fancy suit rather than the profession’s traditional smock, the African American barber in this print is portrayed as a “dandy”—someone putting on airs—who holds a razor engraved “Magnum Don” (“great gentleman”). In contrast, his white customer is dressed much more modestly, and his jacket hangs on a coat rack labeled “plain body.” Despite the racist overtones of the image, it nevertheless shows how common it was for whites to seek out the specialized barbering skills of blacks.

It should come as no surprise that we associate Stetson hats with the American West, since John B. Stetson’s (1830-1906) earliest and most iconic model was the “Boss of the Plains,” fashioned after a rugged hat he made for himself while prospecting for gold in Colorado.

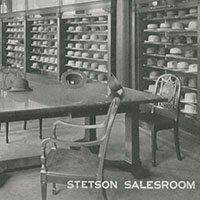

Stetson’s story, though, is fundamentally Philadelphian. The enterprising son of a hatter, he settled in the city in 1865, establishing what became the most successful hat manufactory in the world, producing nearly two million hats a year by 1906. The company made both “staple” (cowboy) hats for daily wear outdoors, and “dress” hats, including bowlers, fedoras, boaters, and top hats.

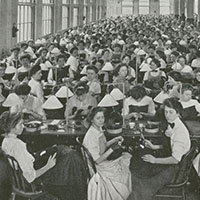

Hat-making was labor-intensive and required several steps, as evident in these images. The fur first had to be treated, removed from the hides, and cleaned. Then it was felted, or shrunk, around hat molds. Hats were then shaped, dyed, trimmed, and finished with ribbons. Such efforts required a massive workforce: Stetson was employing 5,400 workers by 1915. In order to serve its retail customers around the world, the company also capitalized on vertical integration – even the ribbon for trimmings (estimated at millions of yards), was woven on site.

The nine-acre hat factory had a profound impact on the surrounding lower Kensington neighborhood. A staunch Baptist, Stetson provided banking, healthcare, housing, and other services for his employees in order to keep them motivated and loyal. Whether this was good-intentioned philanthropy or Stetson’s paternalistic attempt to create, essentially, a company town within the city is open to interpretation. Beyond dispute, however, is that the company kept countless Philadelphians employed for over a century, until the flagship factory closed in 1971. The Stetson Building, once the company’s retail storefront, still stands at 13th and Sansom Streets.

John B. Stetson Company. [Philadelphia?, ca. 1910]. Photomechanical postcards.

Although John B. Stetson Company is best known for its “Boss of the Plains” cowboy hat, the Philadelphia company produced many other styles, including straw boaters, women’s “novelty” hats, and felted fur top hats. The one displayed here is marked with the initials “H.N.M.” inside the brim, and the leather trunk, lined with red velvet, was especially-made for the hat and could be locked.

In addition to umbrellas and hat cases, Oliver Brooks provided his customers with imported and domestically-produced hats fashioned from a variety of materials including otter and seal. In 1842, he patented a way to use fur-finishing techniques to make hats out of cassimere, or wool.

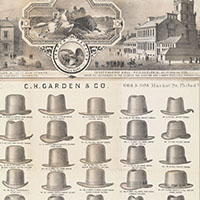

Almost ten million people flocked to Philadelphia when it hosted the Centennial Exposition in 1876. The world’s fair enabled the city to showcase its commercial strength on an international stage. Businesses like C.H. Garden’s hat manufactory (est. 1841) used the fair as a convenient marketing opportunity. The Centennial Circular features over sixty different kinds of hats on the front, and the text on the back encourages visitors to come to town early in order to explore the city’s many attractions. Springville, where this particular copy was sent, is a town in northeastern Pennsylvania.

C.H. Garden & Co. Centennial Circular 1876. Philadelphia: F. Moras, [1876]. Lithograph.

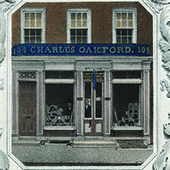

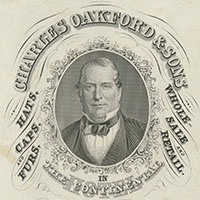

Opening his Philadelphia business in 1827, Charles Oakford was one of the most successful hatters in the country, serving markets as close as Trenton and as far away as Mexico. A skilled furrier, he also made and sold luxurious boas, muffs, collars, cuffs, capes, and robes for the ladies. This advertisement, showing Oakford standing at the entrance to his store, is framed by various military hats, illustrating another of the establishment’s specialties.

Having for decades operated one of the poshest hat and fur stores in the country, Charles Oakford moved his business to the fashionable Continental Hotel on Chestnut Street as soon as the new building was ready for tenants in 1860. Continuing to cater to the rising middle class, this place, too, was a picture of elegance. Although Oakford died in 1862—not long after his portrait was engraved for this trade card—his sons continued the business for decades.

Wm. H. Oakford. [Philadelphia, ca. 1885]. Chromolithograph trade cards.

Josiah Richelderfer offered a variety of men’s and women’s goods including gloves, shirts, over-gaiters (to protect trousers from the elements), and leggings made of leather, velveteen, and satin. But he was best known for his celluloid collars and cuffs, made from an early kind of plastic. Detachable collars and cuffs meant shirts did not have to be washed as often, and Richelderfer’s were waterproof, to boot.