Ready to Wear

In partnership with his brother in-law Nathan Brown, John Wanamaker opened his first store in 1861. Called “Oak Hall,” it was located at 6th and Market Streets.

From his earliest days in business Wanamaker showed an aptitude not only for retailing, but advertising: “The time to advertise is all the time,” he once remarked. He was one of the first retailers to take out a full-page ad in a newspaper, he offered free in-store concerts, and hired professional artists to design illustrations and window displays. He even used celluloid, an early form of plastic meant to imitate ivory, to produce advertising cards such as this one.

In 1875 Wanamaker purchased abandoned Pennsylvania Railroad sheds and a year later opened his “Grand Depot” at 13th and Market Streets, thus establishing Philadelphia’s first department store.

This bird’s eye view, showing Wanamaker’s proximity to City Hall, the Masonic Temple, the Pennsylvania Railroad Station at Broad Street, and the United States Mint, illustrates just how central the “palace of consumption” was to Philadelphia’s identity.

At the time touted as “the largest space in the world devoted to retail selling on a single floor,” Wanamaker’s featured circular counters that surrounded a central gas-lit tent for the display of women’s ball gowns. The goods on offer, indicated by the floor plan on the right, included everything from jewelry to cutlery, art pottery to books, men’s clothing to stationery.

In order to keep prices low and inventory turnover high, John Wanamaker created special sale days to move slow-selling goods at “dull” times. In January of 1878, he ran his first “White Sale” to liquidate bed sheets and other basic linens. This catalog, from 1901, listed goods for the “Annual Sale of White,” which he promised was bigger and better than ever.

While magazines such as Godey’s popularized the idea that the best fashions came from London and Paris, turn-of-the-century department stores made those fashion ideals a reality for their middle-class customers. Merchants like John Wanamaker (1838-1922) hired buyers to travel to Europe in order to bring back the “latest novelties.” Wanamaker’s son Rodman (1863-1928), one of his most trusted agents, lived in Paris for over ten years before returning to manage the New York City branch of the family business.

In 1909, on the site of the Grand Depot, Wanamaker began construction on what would become the most modern department store in the country. From the depths of this pit, photographed by noted Philadelphia photographer William Rau, he erected a commercial empire.

When completed in 1912, Wanamaker’s new “monster establishment” comprised almost two million square feet, stood twelve stories tall, and featured several galleries. It was designed by renowned architect Daniel Burnham, who described it as “the most monumental commercial structure ever erected anywhere in the world.” Its state-of-the-art amenities—including electric lighting, telephones, “moving stairways” (escalators), a tea room, opulent ladies’ lounges, painted murals, and even in-store childcare—helped transform shopping from drudgery into an experience.

The new Wanamaker’s building, dedicated by President William Howard Taft in 1911, was perhaps best known for its iconic central atrium. The Grand Court was lined with marble and featured what is still one of the world’s largest pipe organs, first displayed in 1904 at the St. Louis World’s Fair.

An intensely religious man, John Wanamaker tried to reconcile his spiritual beliefs with his commercial aspirations: he didn’t advertise or allow organ concerts on Sundays (the latter policy still enforced), designed his stores to look like cathedrals, and decorated the interiors to mark Christian holidays. Although he died in 1922, this photograph of the Grand Court during the 1943 Christmas season, bedecked with wreaths and illuminated trees, shows his enduring legacy. A service flag with a central star recording the number of Wanamaker employees serving in World War II hangs below the organ.

The large bronze eagle in Wanamaker’s Grand Court remains an important Philadelphia landmark. Like the pipe organ, the eagle, by sculptor August Gaul, was first displayed at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. Weighing some 2,500 pounds, the sculpture was so heavy that Wanamaker had to reinforce the floor beneath it with steel girders. For decades, “Meet me at the Eagle” was a common phrase among local shoppers.

By the first decades of the 20th century large retailers in major cities sought out rights to build displays within underground rail systems, making these show windows some of the most costly and desirable. Philadelphia retailers were no exception. The most sophisticated display techniques were used even below ground — including electric lighting, painted murals, and life-like mannequins made of molded papier-mâché and wax.

William H. Burwell (1908-2000), father of Library Company member Walton C. Burwell, purchased this Wanamaker’s suit in the late 1930s or early 1940s. It was designed in the quintessential style of the time – with wide lapels and a fitted waist. The accompanying photo shows the nattily-dressed Burwell (center) with two equally well-dressed friends, all with straw boaters in hand.

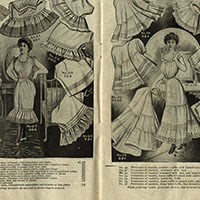

Founded by Quakers Justus C. Strawbridge (1838-1911) and Isaac H. Clothier (1837-1921), Strawbridge & Clothier opened in 1868 and was situated on the northwest corner of 8th and Market Streets in a building that was once Thomas Jefferson’s office while he was Secretary of State. The firm soon replaced the original structure with one that was five stories high, and expanded into neighboring buildings as well. The business was sold to the May Department Store Company in 1996; after being in business for 138 years, it closed in 2006. This architectural drawing shows the front façade of Strawbridge’s circa 1903, as it extended from 825-831 Market Street.

Colorfully printed trade cards became a popular form of advertising after the Centennial Exposition of 1876. Strawbridge & Clothier produced humorous trade cards including this “metamorphic,” which shows a group of boys before and after they have been outfitted with clothes from the famed department store.

Strawbridge & Clothier. [ca. 1880s]. Chromolithograph trade card.

In 1928, Strawbridge’s replaced its earlier edifice, rendered in the architectural drawing above, with one in a Beaux Arts style, shown here. It was designed by the Philadelphia architectural firm Simon & Simon. Costing some $10 million when it was finished during the Great Depression in 1932, the project nearly bankrupted the company.

These interior views of Strawbridge’s show some of the most innovative retailing strategies in use at the time. Fans kept fresh air circulating on sales floors, plants added the lushness of nature, and electric lighting enabled shopping at night. Like museums, department stores also used large glass cases, placing goods on prominent display yet keeping them tantalizingly out of reach at the same time.

Strawbridge & Clothier – Philadelphia’s Foremost Store. [ca. 1910]. Photolithograph postcards.

In order to encourage women to shop, Philadelphia’s department stores offered guaranteed refunds on returns and free delivery, both retailing innovations. These images show Strawbridge’s and Wanamaker’s horse-drawn vans, which not only shuttled goods from warehouses to stores and made home deliveries, but also served as mobile advertisements that would appear throughout the city.

The fashion needs of the city’s diverse residents were met not only by high-end retailers on Chestnut Street, but also by clothing depots, which were often situated on Market Street. By offering cheap, ready-made suits for the masses, the Great Central Depot and similar stores helped to democratize fashion, and hence respectability, among the public.

Cheap clothing stores offered customers more accessible alternatives to the custom-made outfits available at tailoring establishments. What they lacked in service and quality cheap stores made up for in price. At Jones & Co.’s One Price Clothing Store, for instance, “every one [was] his own salesman,” choosing clothing off the rack rather than getting a custom fit. Like the clothes themselves, the pricing system was also uniform. During this time, one price did not mean everything in the store cost the same, but that customers paid the same, regardless of who they were. There was no room for haggling or preferential treatment. In the words of the advertisement, “all must buy alike.”

Established in 1859, Charles Stokes & Co.’s One Price Clothing Store was located in the sprawling Continental Hotel, at the time the largest hotel in the country. Along with military goods, the retailer offered “the peculiar system of having the price marked plainly on all of the goods.” Furnished with state-of-the-art gas lighting, marble floors, and attentive clerks, Stokes hoped to compete with more elite establishments by providing ready-made goods at low prices.

Located on Market Street, Bennett’s Tower of Fashion was one of the first large clothing emporiums in the country, offering ready-made suits at both wholesale and retail. Like many successful 19th-century Philadelphians, Joseph Bennett used his wealth for philanthropic purposes, leaving money to the Chestnut Street Opera, establishing a Methodist orphanage, and bequeathing real estate in West Philadelphia to the University of Pennsylvania for the benefit of women’s education.