Fashion Revolutions

In the 18th century, Philadelphia was the largest and most fashionable city in the colonies. The rise of imported consumer goods enabled elite men and women to increasingly differentiate themselves from the laboring poor. Wealthy women’s dresses were extravagant, with elbow-length cuffs that “hung down one foot”; they wore big hair to match.

Men adopted the “macaroni” mode. Borrowing British affectations, macaroni men were effeminately dressed in tightly-fitted garments with puffed shirts and overly-styled powdered wigs.

The song Yankee Doodle makes fun of these foppish characters:

“Yankee Doodle went to town

Riding on a pony;

He stuck a feather in his hat,

And called it macaroni.”

It is thought that the verse originated during the French and Indian War, and was sung by British officers satirizing the sorry appearance of the colonial “Yankees” with whom they served. “Doodle” was slang for fool.

Macaroni; Southwark Macaroni; Simpling Macaroni; Farmer Macaroni. London: M. Darly, 1772.

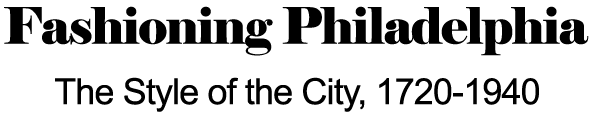

Antiquarian John Fanning Watson (1779-1860) recorded the recollections of older Philadelphians, which he compiled and published in 1830 as the Annals of Philadelphia, the first history of the city. On one of the pages here, a 70-year-old woman has sketched the fashions of her youth. On the other, his mother, Lucy Fanning Watson, has drawn several examples of 18th-century hats, including a Quaker hat made from white beaver, a “mush mellon” bonnet stiffened with whale bones, a night cap styled after Martha Washington’s, and a green silk sun bonnet that could go up or down, like the convertible top on a gig.

Pages from the extra-illustrated manuscript of Watson’s Annals of Philadelphia. Presented to the Library Company by John FanningWatson, 1830.

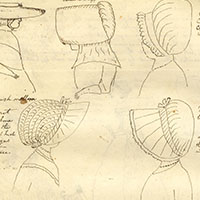

John Fanning Watson appreciated how textiles could become relics that held both historical and emotional importance. The pages reproduced here, from the extra-illustrated edition of his Annals of Philadelphia, contain fabric swatches—satins, calicoes, and silks—from garments dating back to 1720. Next to each, Watson recorded the remnant’s association with a specific person. One is a piece of his grandmother’s wedding dress, and the other, a bit of “the author’s first frock!” The small square of black silk velvet, “very thick & heavy,” was once part of a coat worn by Benjamin Franklin.

Pages from the extra-illustrated manuscript of Watson’s Annals of Philadelphia. Presented to the Library Company by John Fanning Watson, 1830.

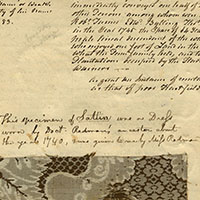

Beginning in the 1760s, imported goods took on political meaning. British textiles, in particular, came to symbolize political oppression, the vices of luxury, and America’s continued economic dependence on Great Britain. Many began championing “homespun,” less refined clothing made of materials that were grown and processed domestically. The machine shown in this diagram, invented by Philadelphian Christopher Tully, would both spin and weave textile fibers. Colonists believed that controlling the resources and means of production would enable them to break free of imperial control.

In the 18th century, elite Philadelphians set the fashion standards for the rest of the colonies, and they closely imitated British styles. But these styles, often extreme and absurd, were frequently lampooned. This cartoon is titled “The Siege of Cork,” a playful reference to the 17th-century Irish military action. It shows bottles in search of stoppers. They seek the cork that gives shape to the woman’s oversized bustle. Cork is also stuffed beneath her tower of hair, where horsehair, wire, wool batting, and other hair heighteners might also be found.

Philadelphia was occupied by the British from 1777 through 1778. To honor General Howe, the head of the occupying forces, when he was called back to England, John André (1751-1780) and his fellow officers staged an elaborate send-off for their commander. Called the Meschianza (Italian for medley), the all-day party took place on May 18, 1778, and included mock jousting tournaments and a regatta. It culminated in a lavish ball.

André orchestrated the entire event, down to sketching the costume that women were expected to wear. An essential element was the “high roll,” or “Tower”—hair teased and stuffed into great mounds and richly ornamented, after the prevailing British fashion. Some 400 guests attended the Meschianza, many in hopes of finding suitable mates. Believed to be among them was Peggy Shippen, future wife of Benedict Arnold. Others, however, stayed away, deeming the Loyalist party a “shameful scene of Dissipation.”

In the last decades of the 18th century, as host of the Continental Congress and the nation’s capital from 1790 to 1800, Philadelphia was at the center of American politics and culture. People paid a great deal of attention to the appearance of those in the public sphere, whether they were wearing republican homespun or luxurious velveteen.

Rufus Griswold’s The Republican Court, published after the country had endured the Panic of 1857 and was on the brink of war, provided a nostalgic look back on those heady days of the American Republic. He took special note of the fashions of the elite women of the time. Reproduced here is the volume’s portrait of Deborah McClenaghan Stewart (1763-1823), wife of Walter Stewart (1756-1796), an officer in the Pennsylvania militia. She is described as “a beautiful woman and a leader of society.” Known as the “Irish Beauty,” Walter Stewart was equally good looking.

By the end of the 18th century, Philadelphia had become the center of fine cloth and yarn production in America, a result of the influx of skilled textile workers such as John Kean, who came from England, Scotland, and Ireland.

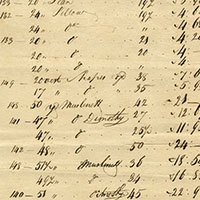

Despite patriotic efforts encouraging Americans to purchase homespun textiles and critics’ frequent tirades against luxury, the variety, availability, and affordability of British imports after the Revolution proved irresistible to American consumers, who could buy many goods cheap at auction. This receipt lists 32 lots of imported textiles, including jean, denim (a sturdy but comfortable form of jean), muslin, dimity (lightweight cotton), and satinette.