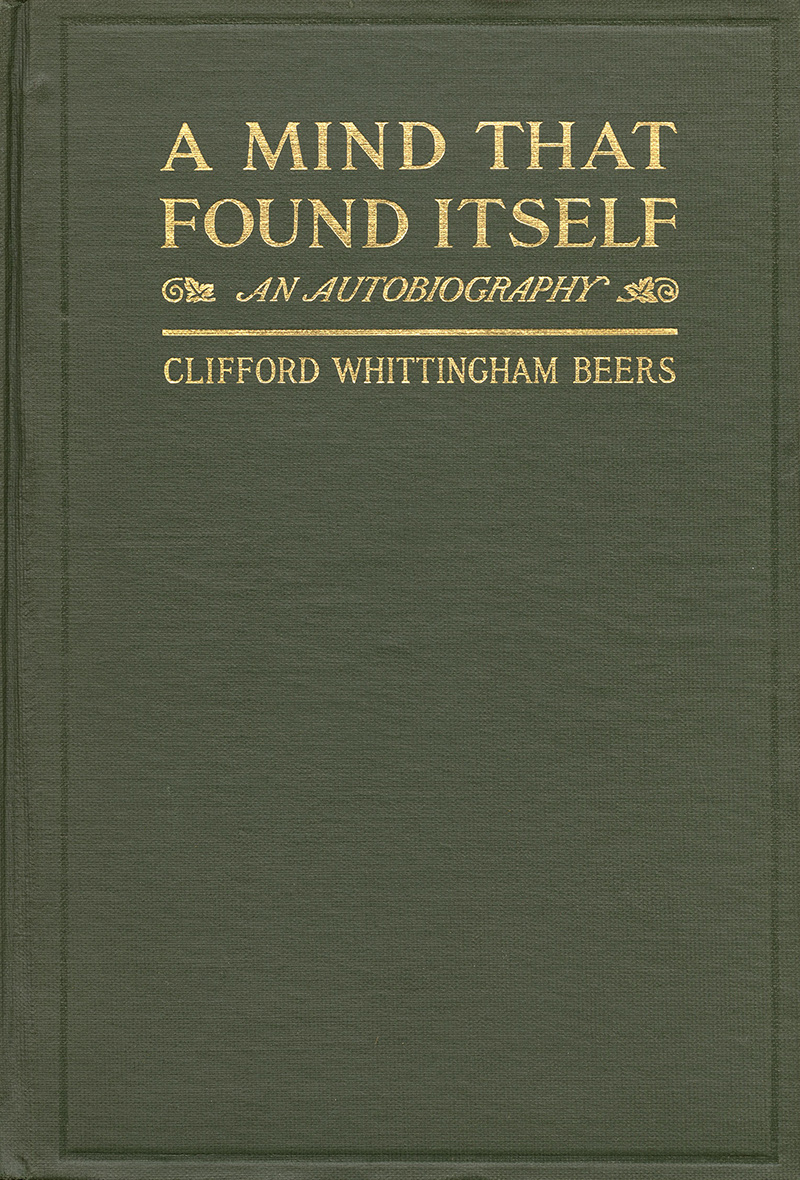

“In order to regain reason’s tottering throne”

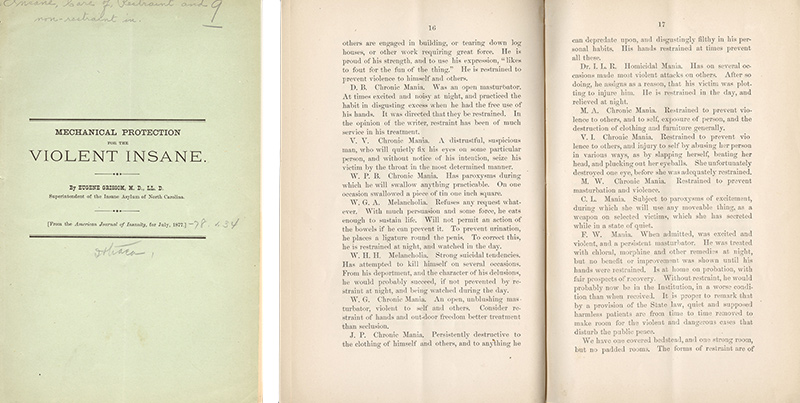

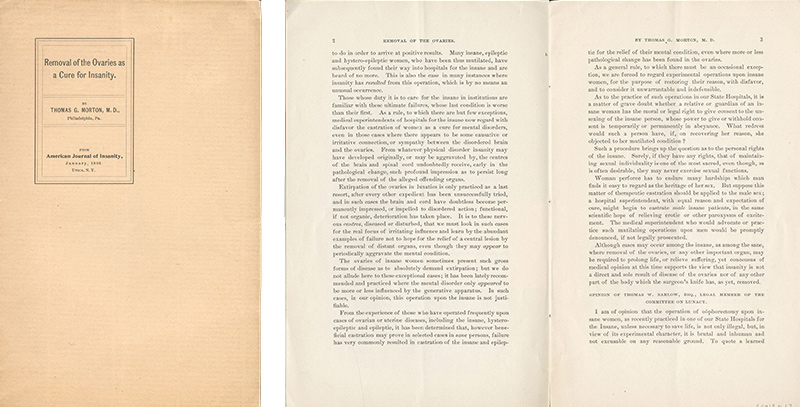

The 19th Century Asylum

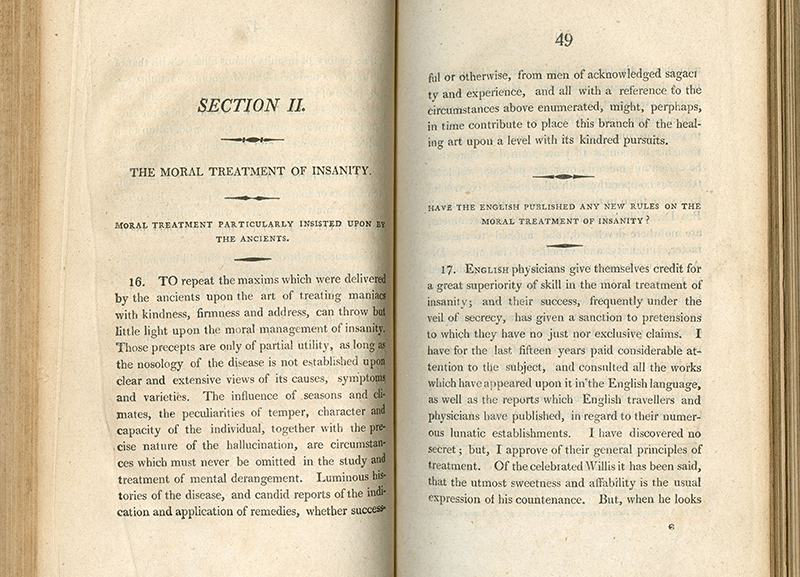

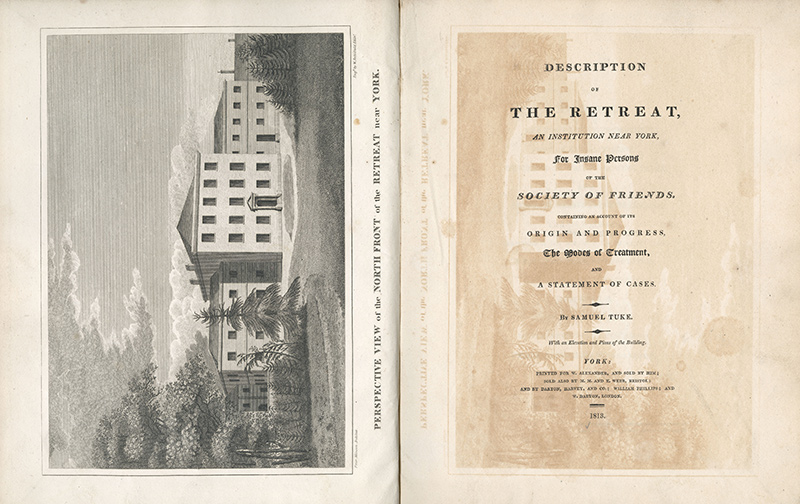

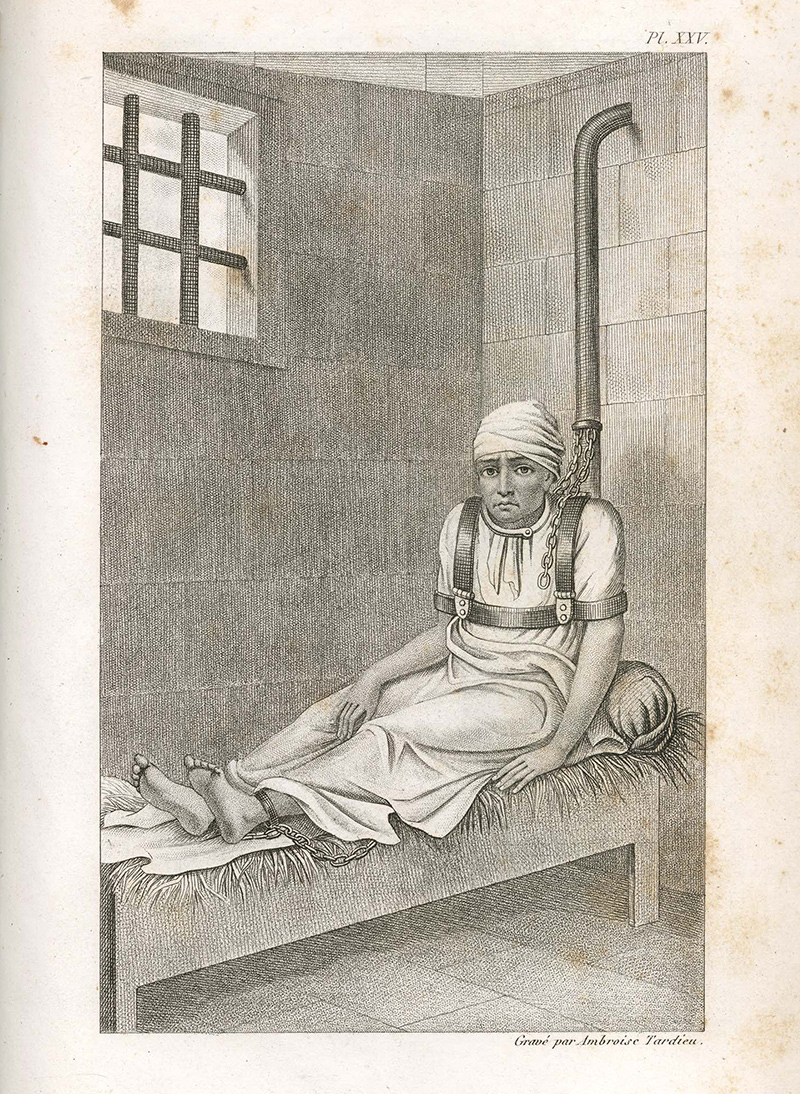

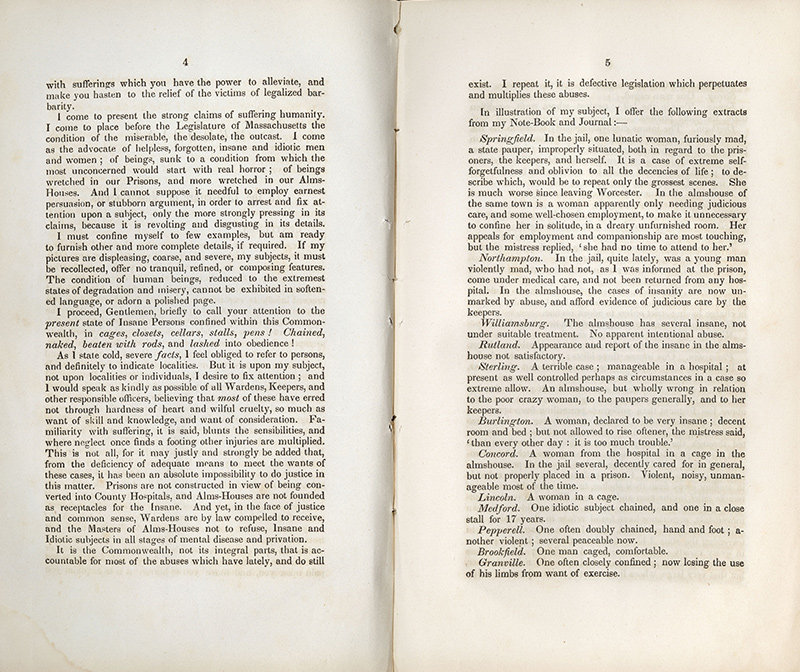

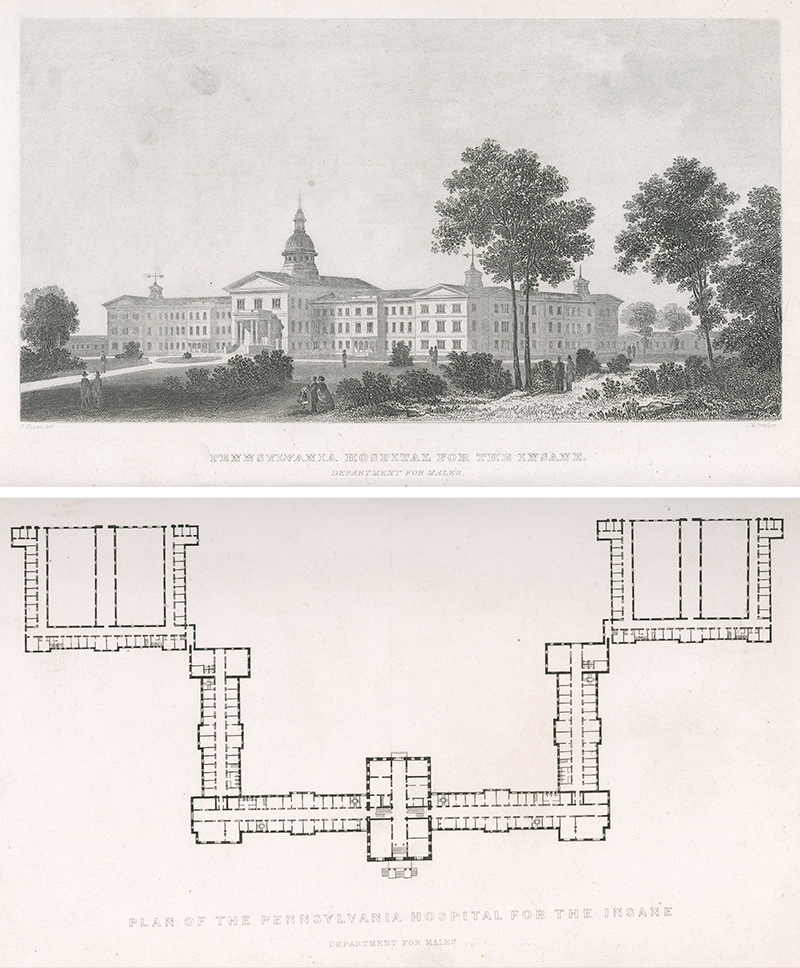

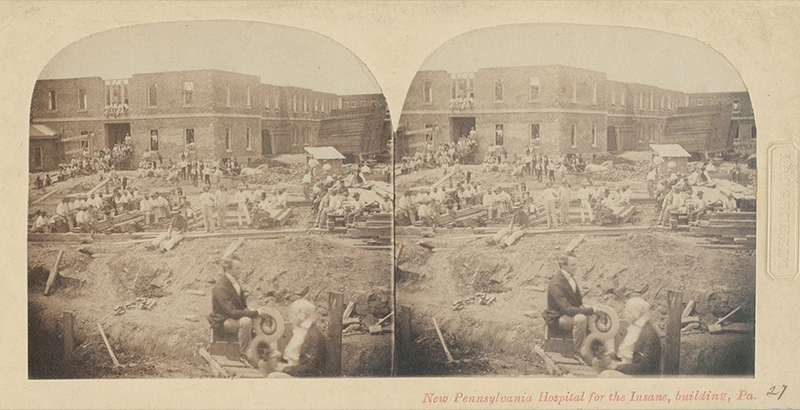

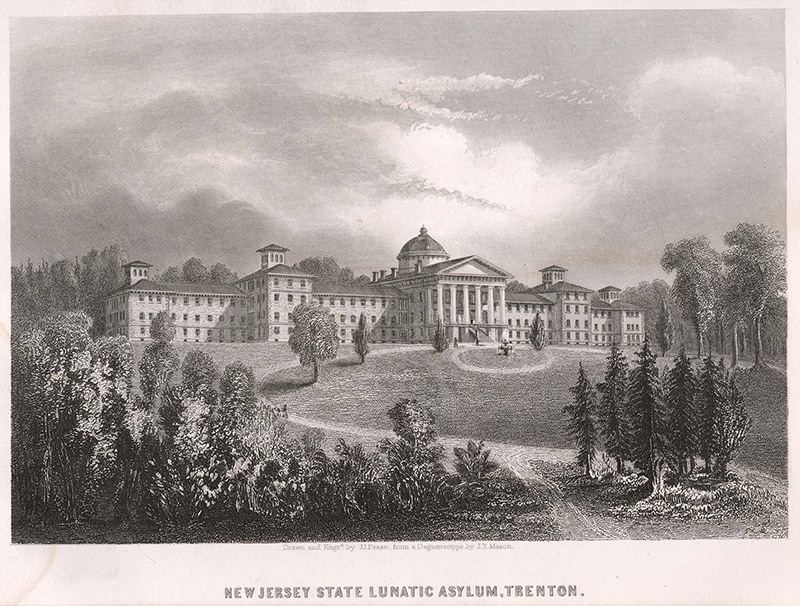

The 19th century saw tremendous change in the care and treatment of mental illness. Names still familiar to many influenced this transformation. In America, we had Rush, Kirkbride, and Dix. In Europe, Pinel, Esquirol, and Tuke. At all stages, those encouraging and instituting change felt that their proposals constituted progress, and in most situations it was concern for those living with mental maladies that drove the change. How, then, could things have gone so wrong that a genre of literature (the “insanity narrative”) developed in response to the repeated failings of this system of care? The usual suspects are to blame: economy, animosity, and fear. Thus, the confluence of the grand intentions and spectacular inadequacies of the 19th century asylum.