“We are traitors to any truth when we suppress the utterance of it”

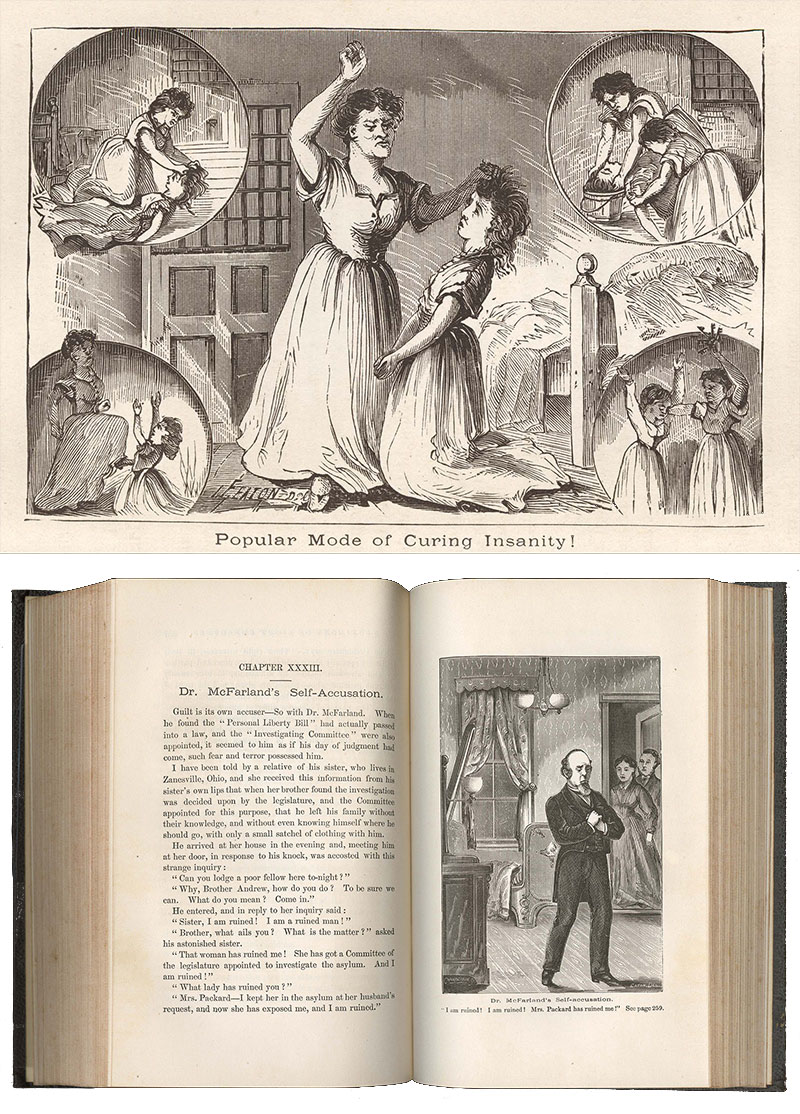

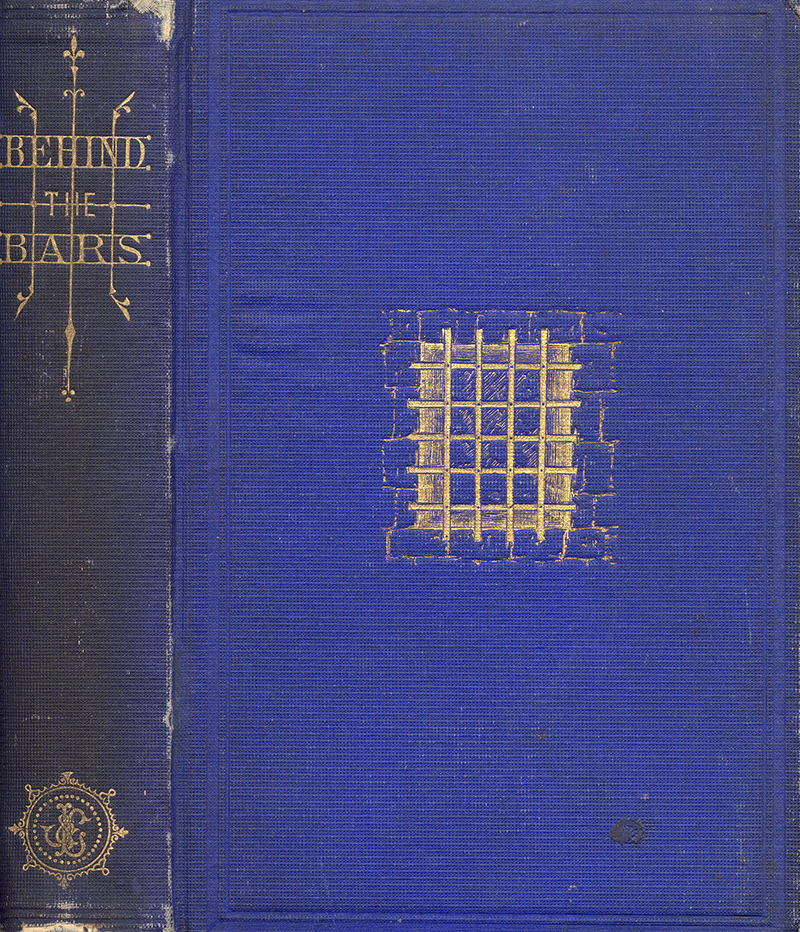

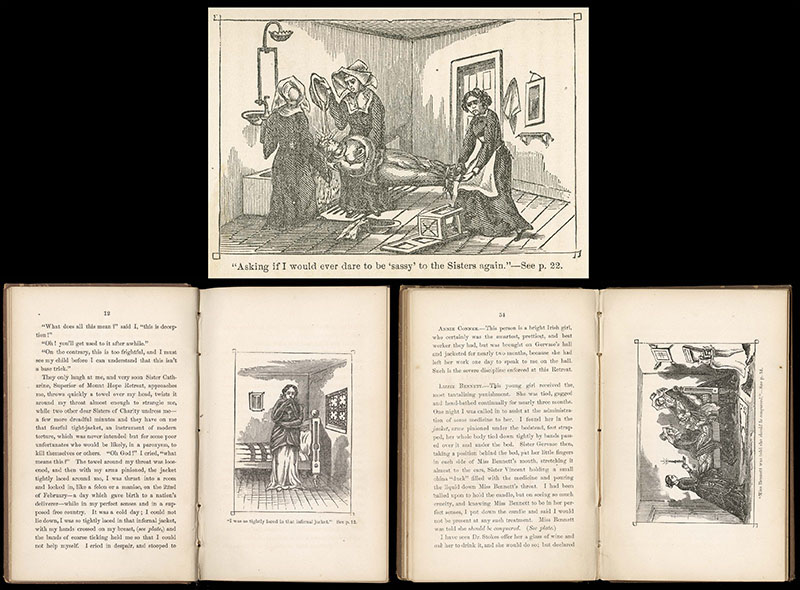

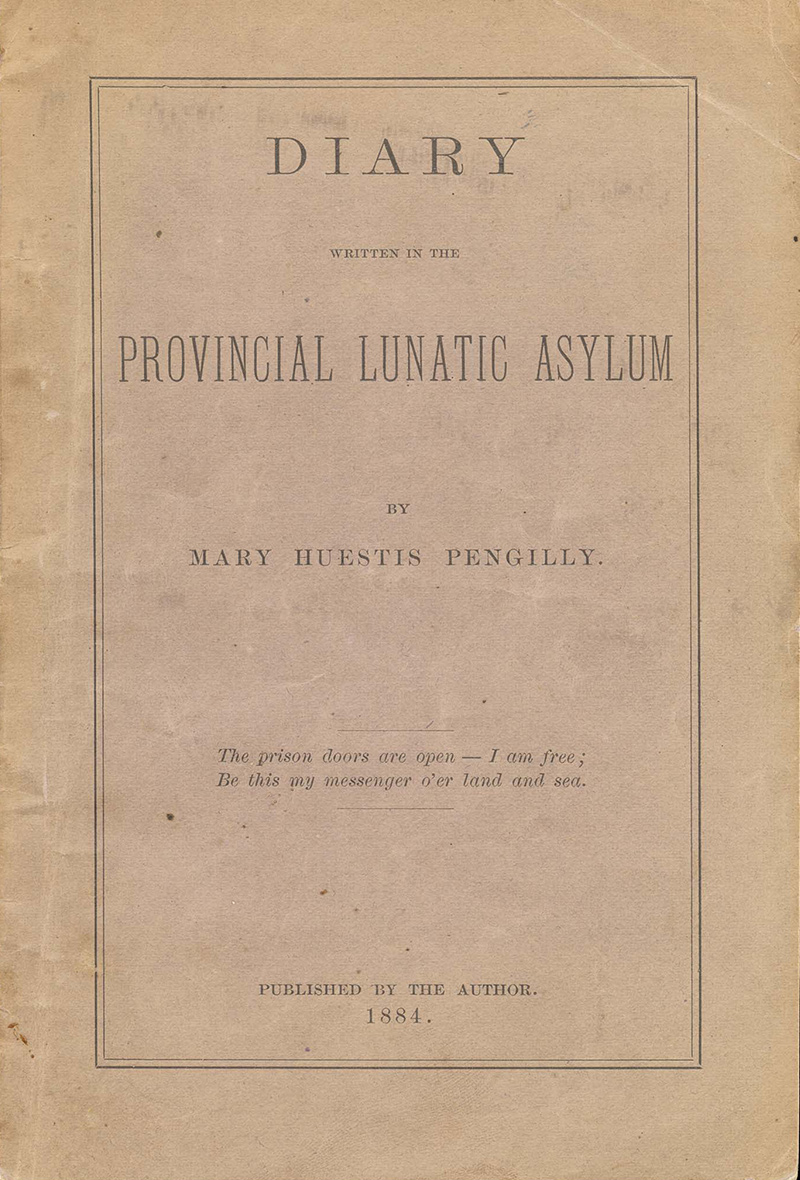

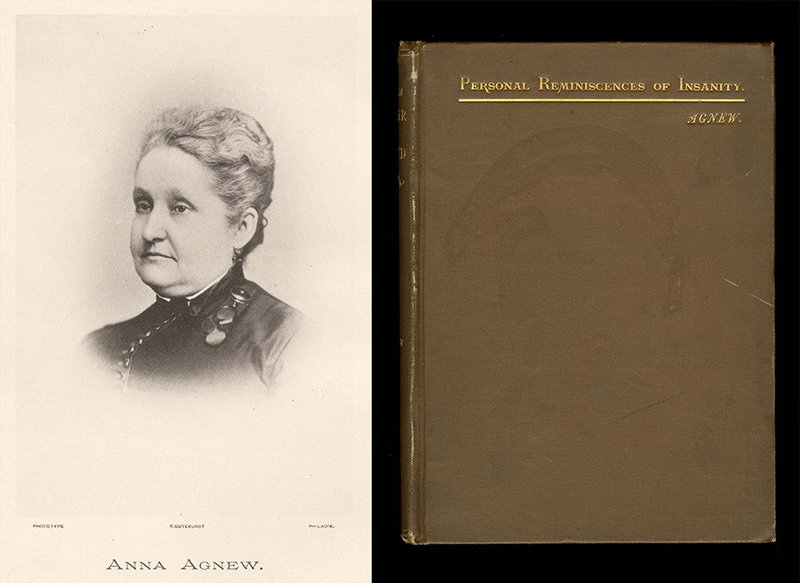

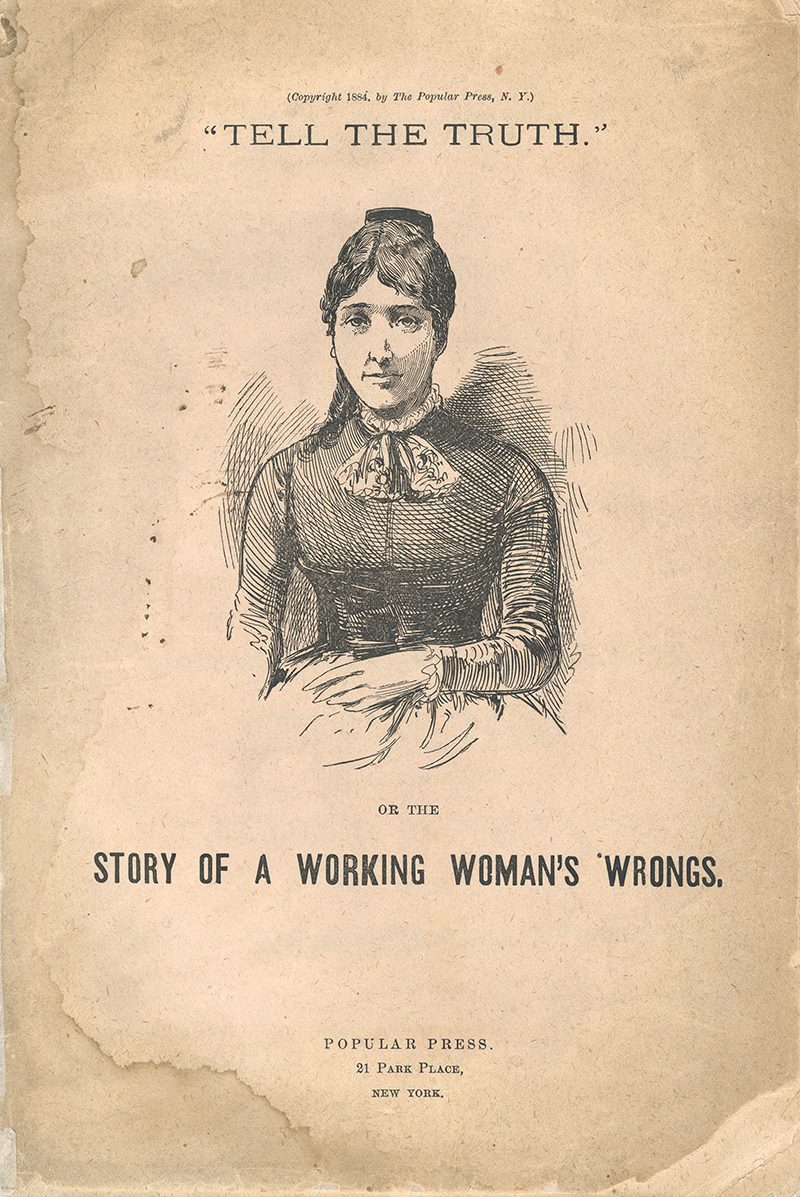

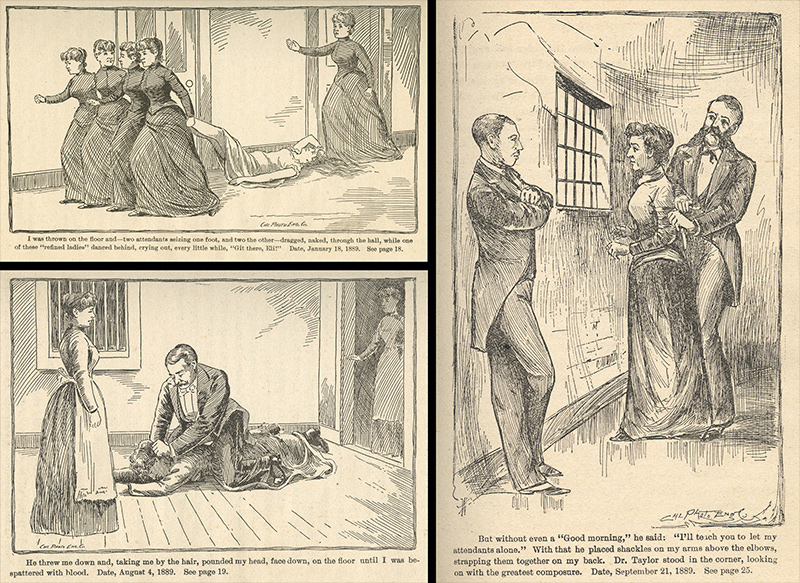

Department for Females

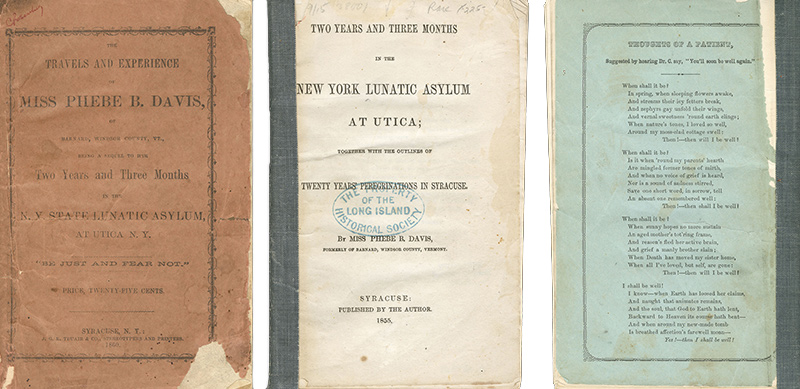

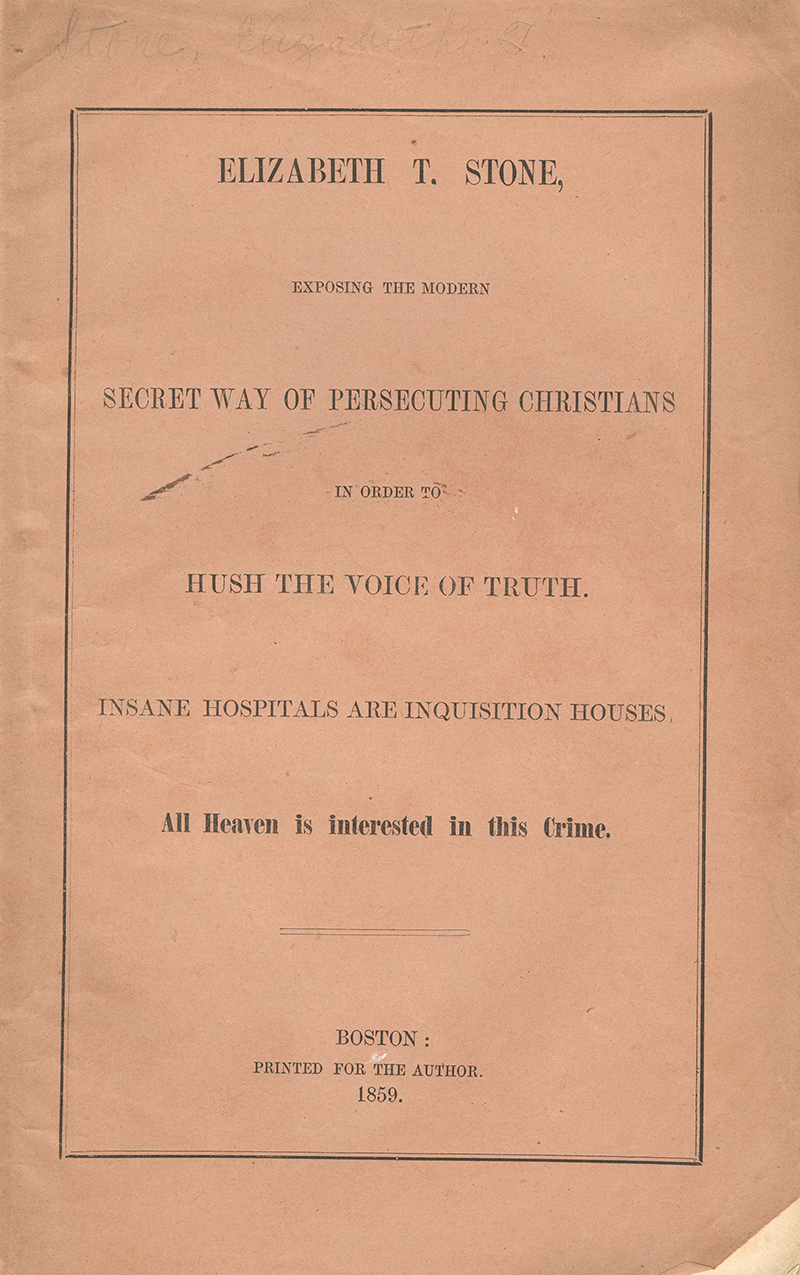

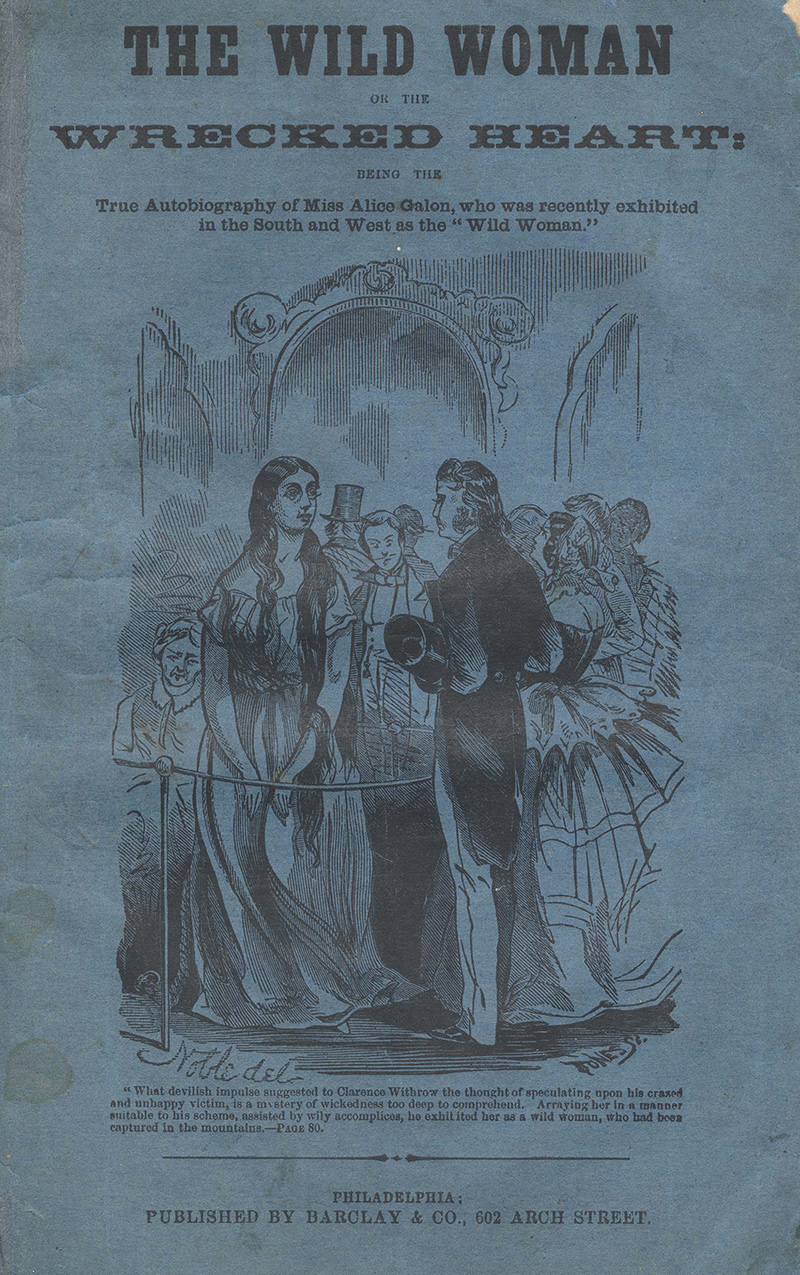

By the mid-nineteenth century, more than half of those institutionalized in the United States were women. Doubly marginalized, being both female and mentally ill, their experiences were distinct from their male counterparts. The narratives of the women in this section tell of the abuse suffered not just at the hands of doctors and attendants, but at the hands of family and the law. They tell of involuntary and wrongful commitment, often by husbands or fathers, and mistreatment as a matter of course. While these women used their narratives to expose and to incite, to advocate for legal rights and better treatment, their published stories are also important works of agency and restoration. Their stories are more than personal, they are political.