“What Can’t Be Cured, Must Be Endured”

More than a Narrative

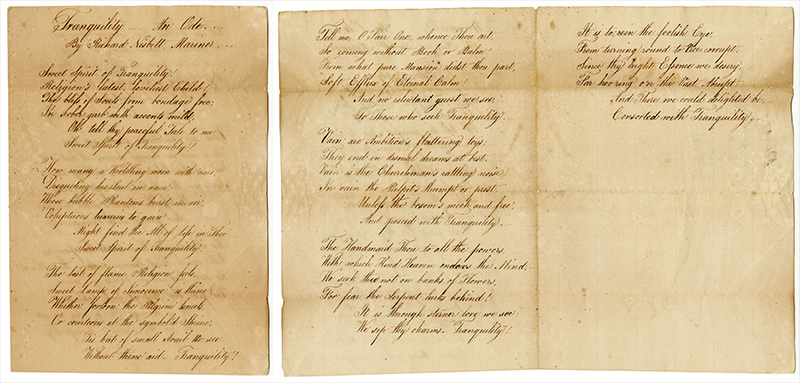

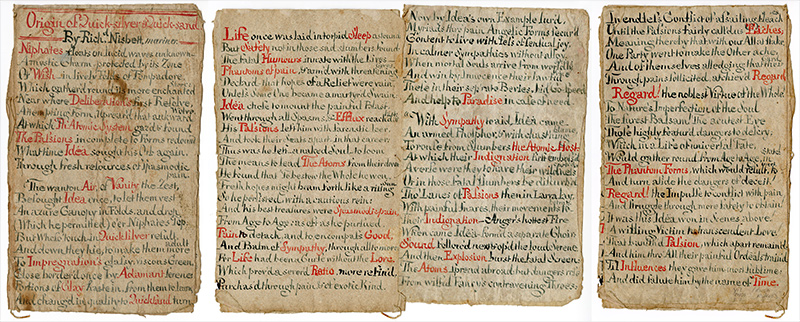

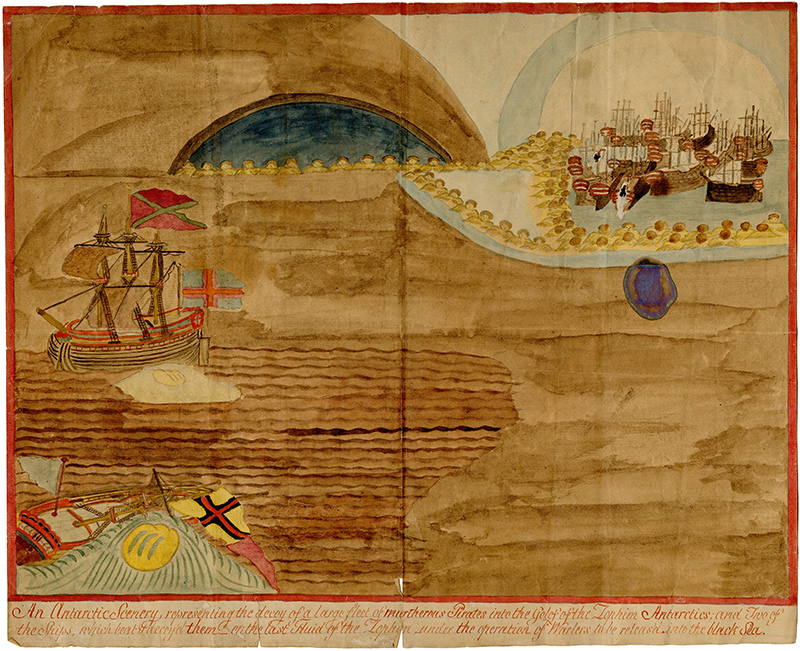

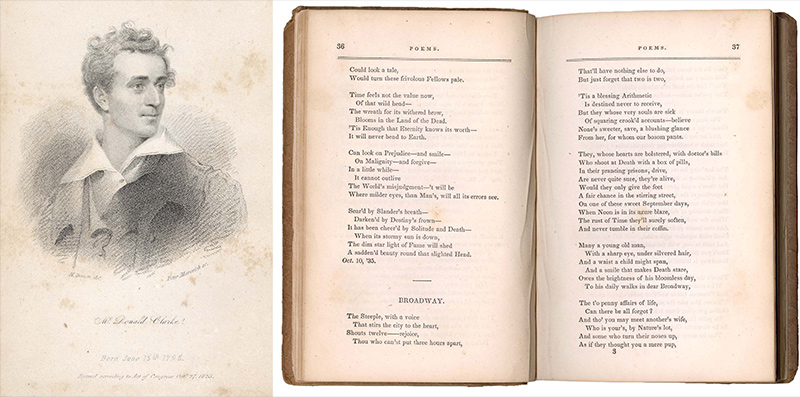

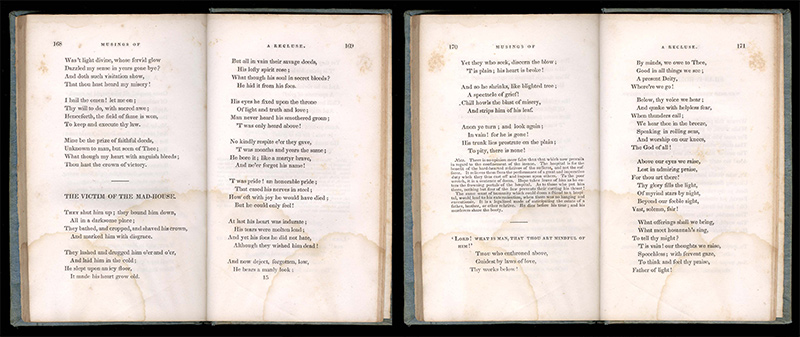

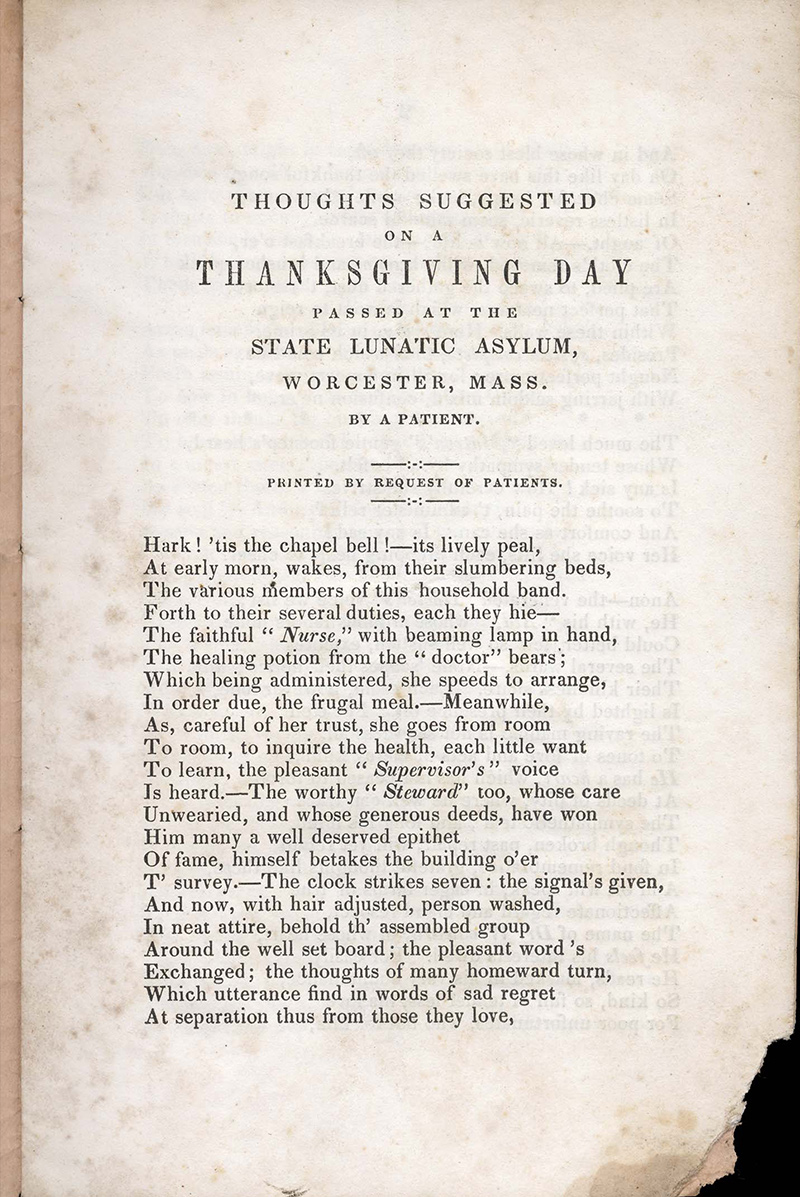

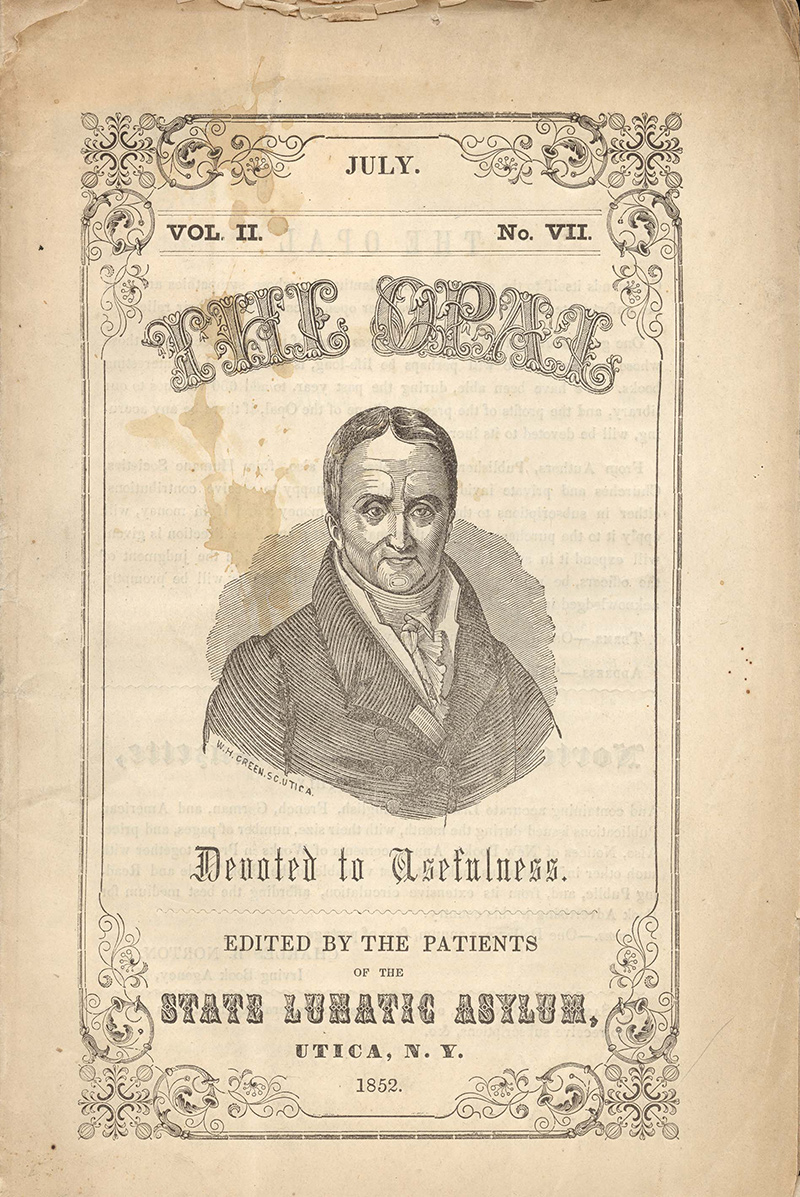

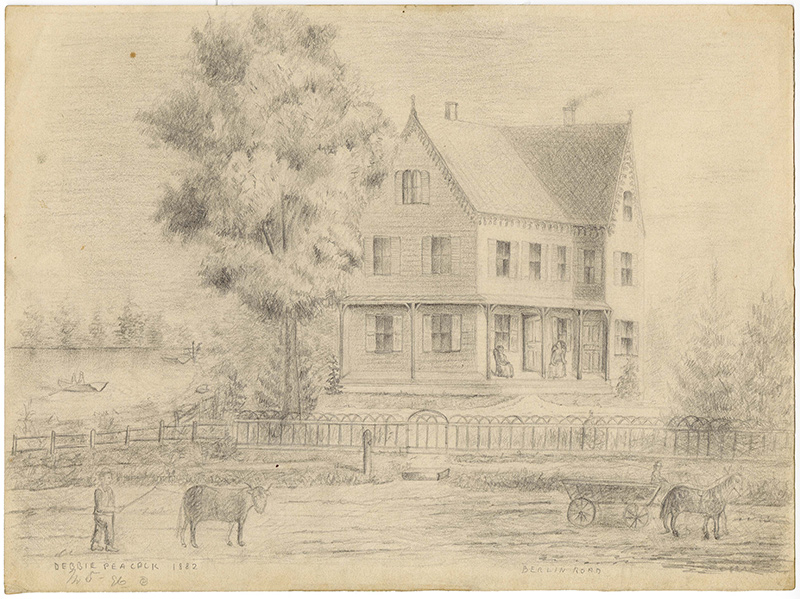

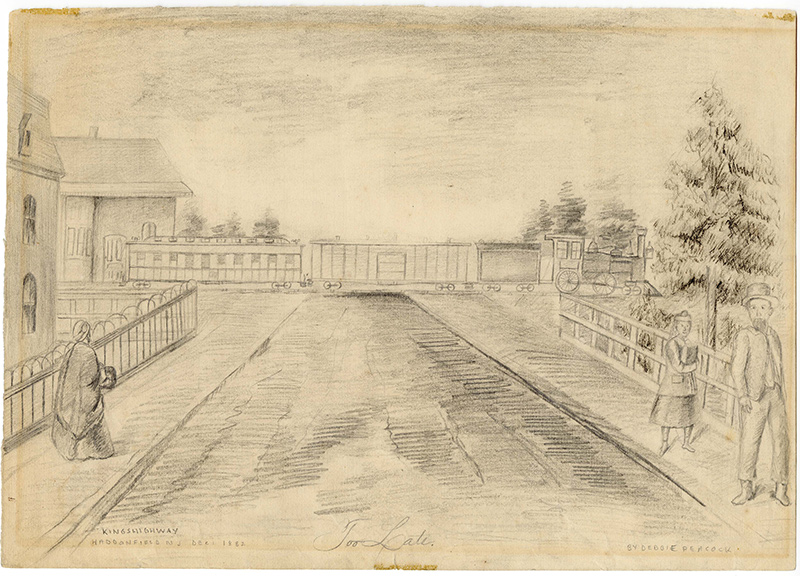

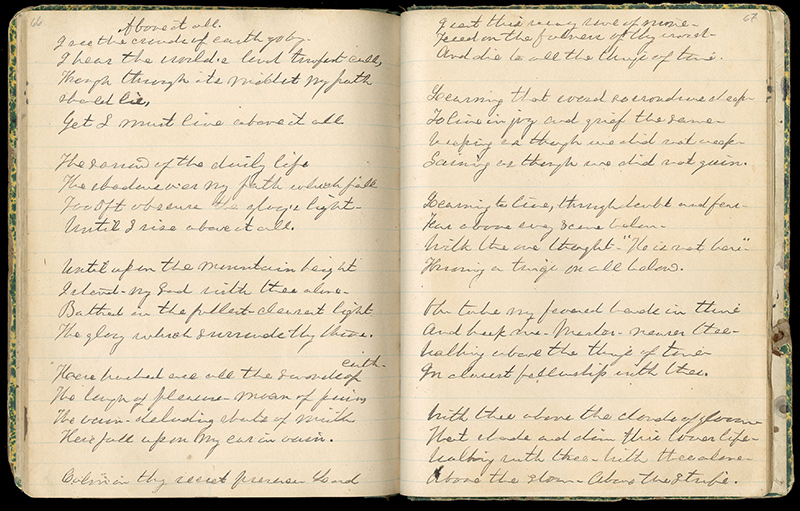

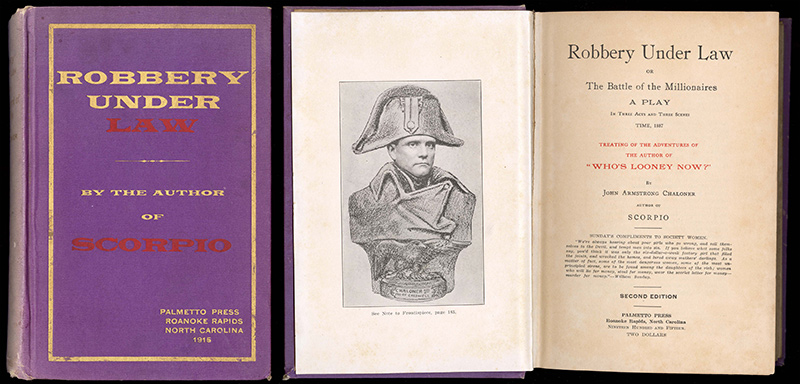

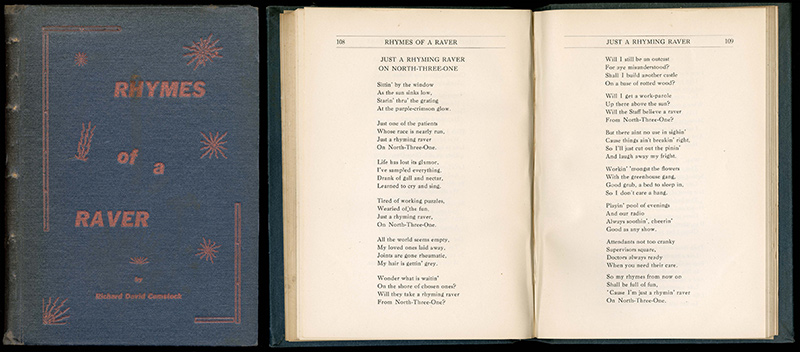

One of the defining tenets of moral treatment as it was conceived was the use of occupational and social activities as a coping mechanism and distraction technique. In institutions that practiced moral therapy, this usually meant working in the garden or the sewing room, the wood shop or the print shop. The less publicly-visible products of this were often blankets and clothes and the very food on the table, but the inmate-generated magazine The Opal is also an example of the outcome of this work. Regardless of whether or not they were recognized as a formal part of therapy, all of the creative pieces shown here stand out especially, as they are loud with the voices of their creators. Sometimes produced while institutionalized, and sometimes before and/or after treatment, the words and images in this section can be seen as a form of narrative but, in many ways, they go beyond that. These pieces ask us to stop and linger over a mark, a word, a curve, or a color, and to reflect on the individual that created it.