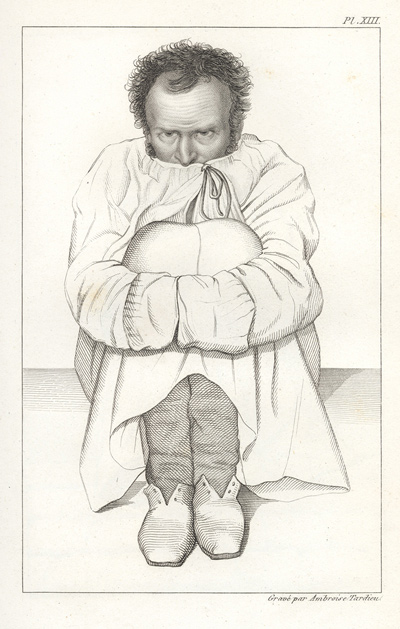

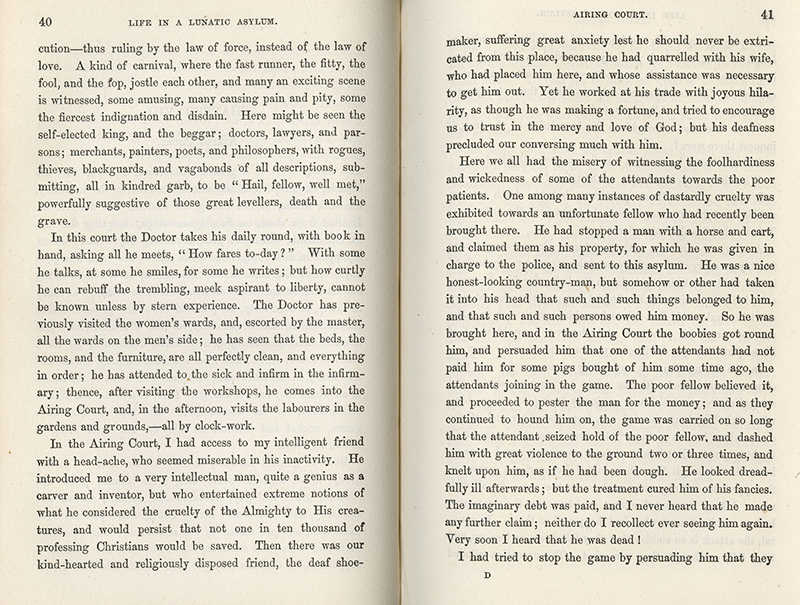

“Unfeeling hearts and cruel hands”

Department for Males

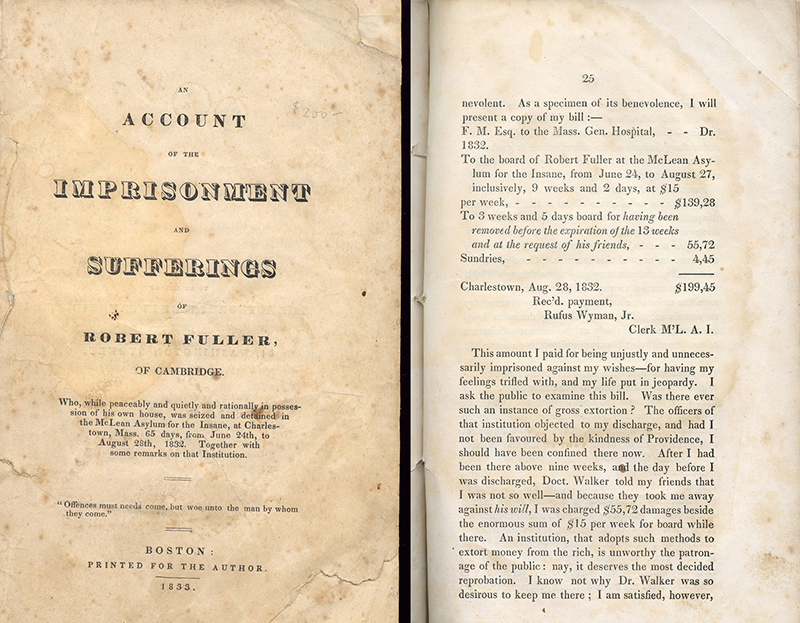

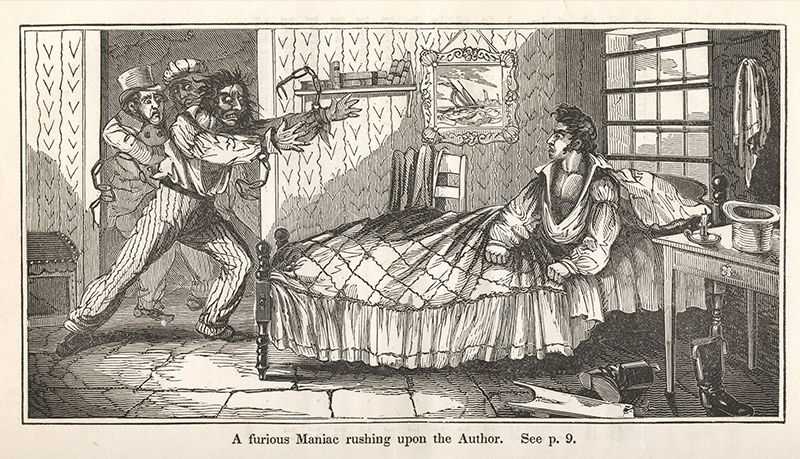

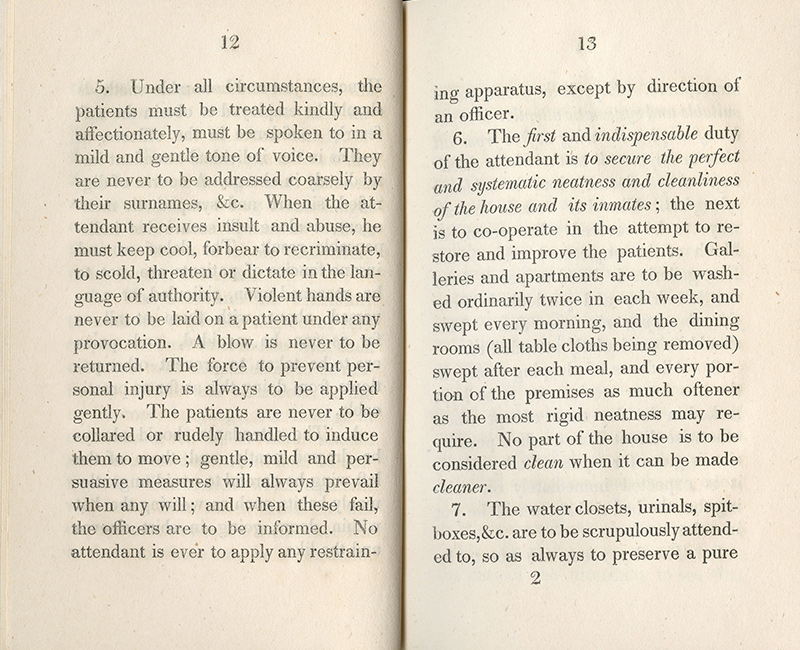

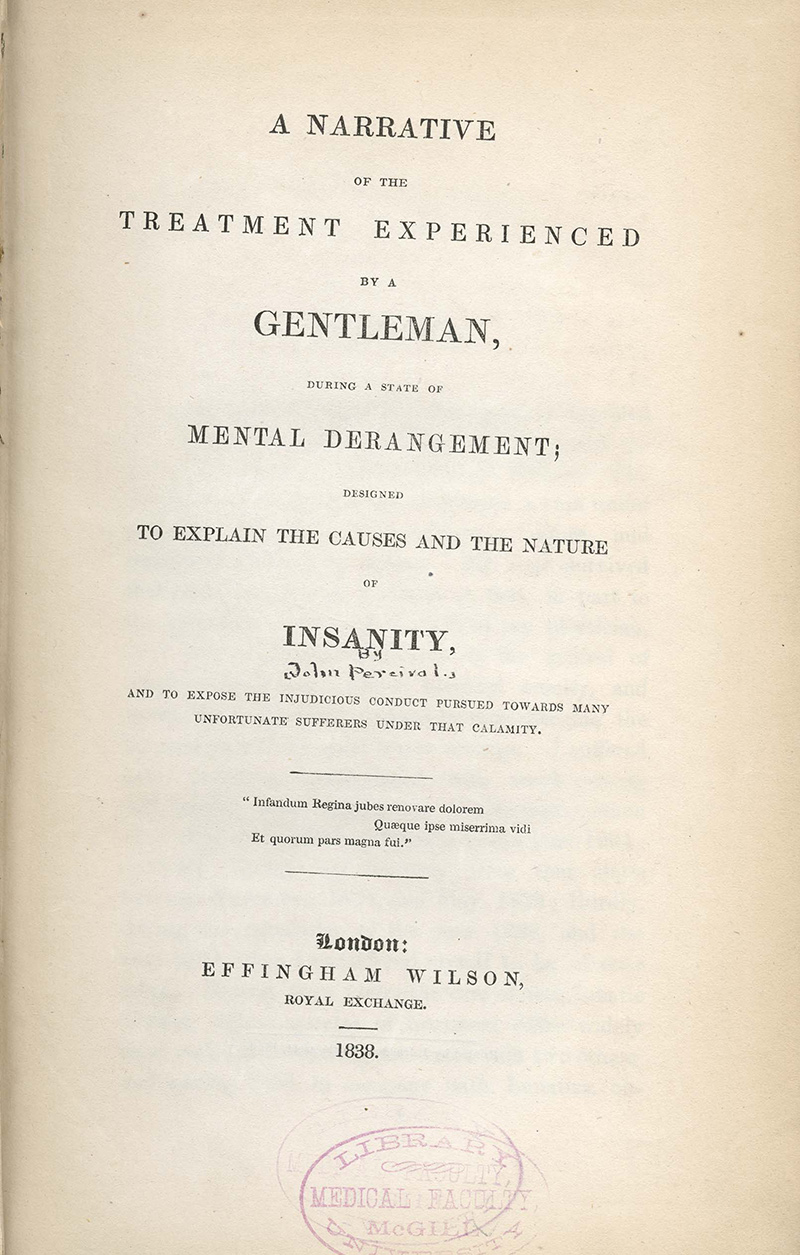

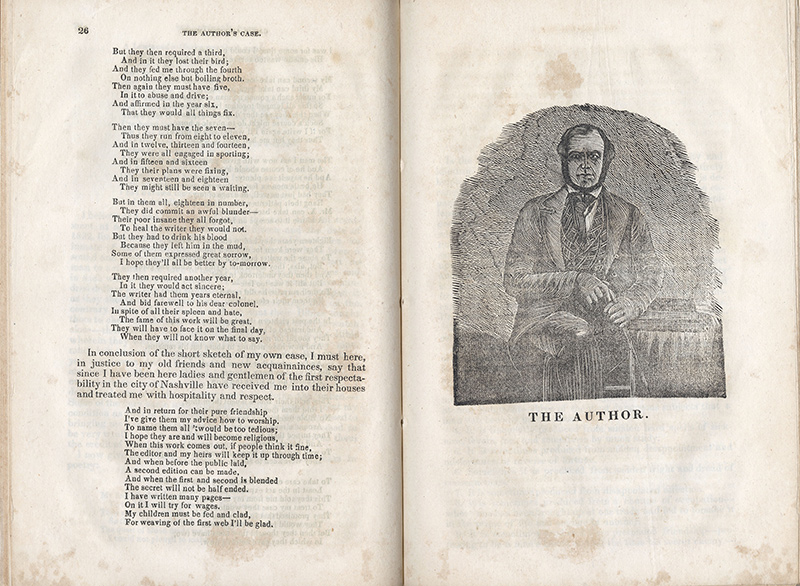

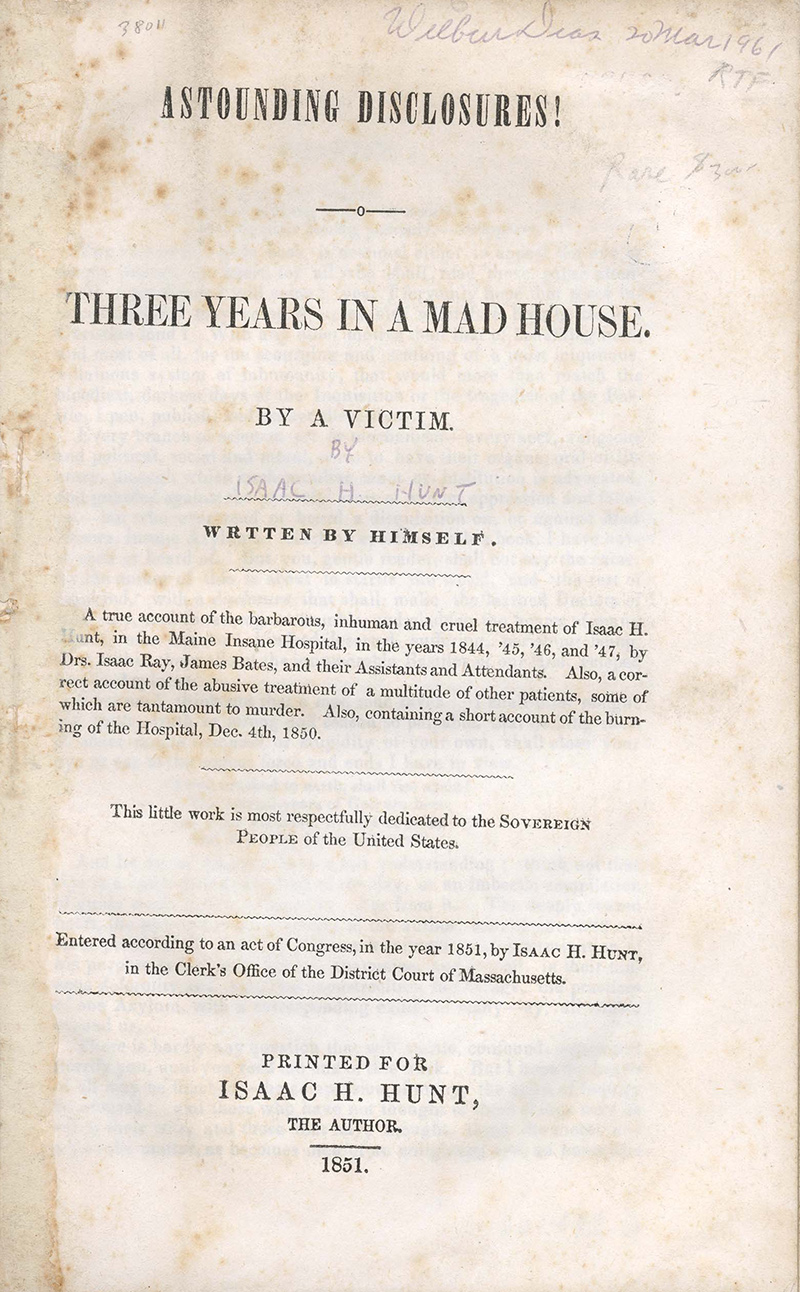

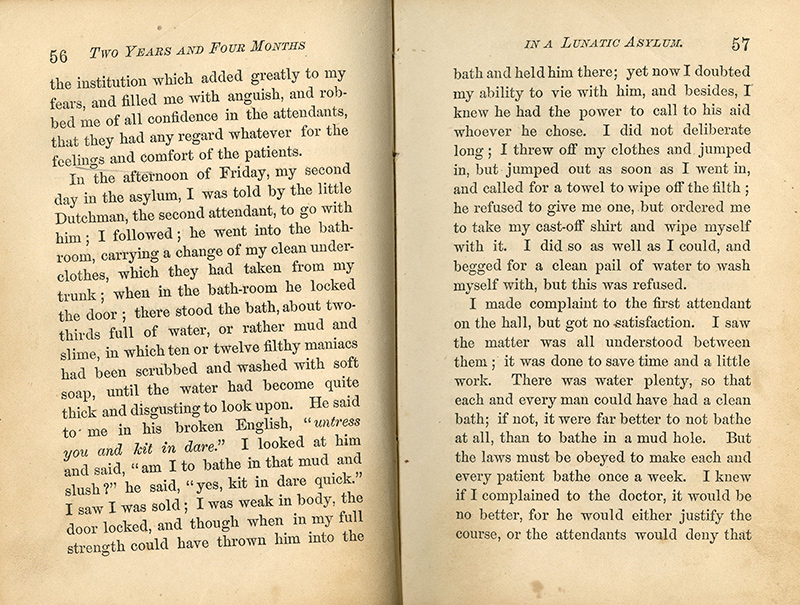

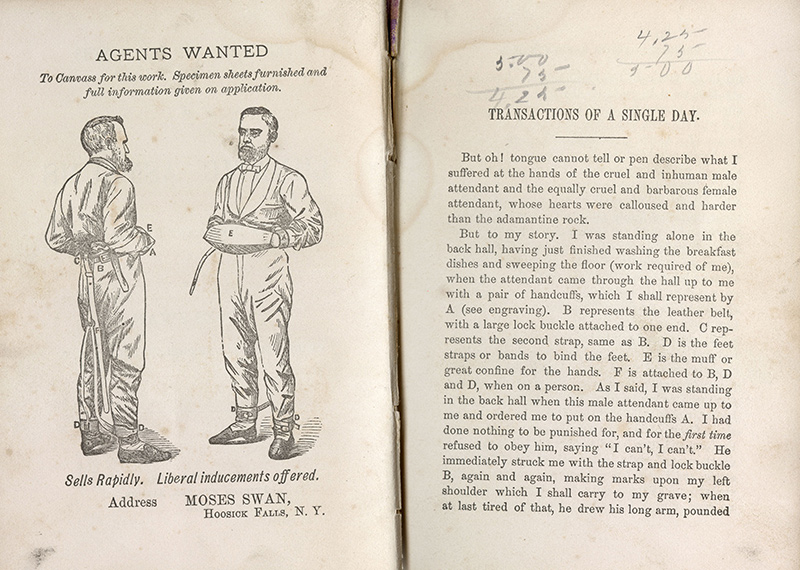

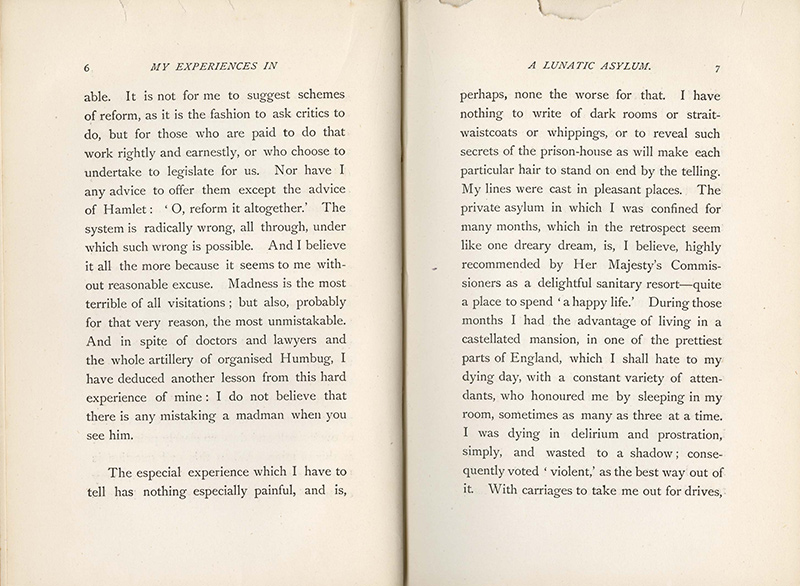

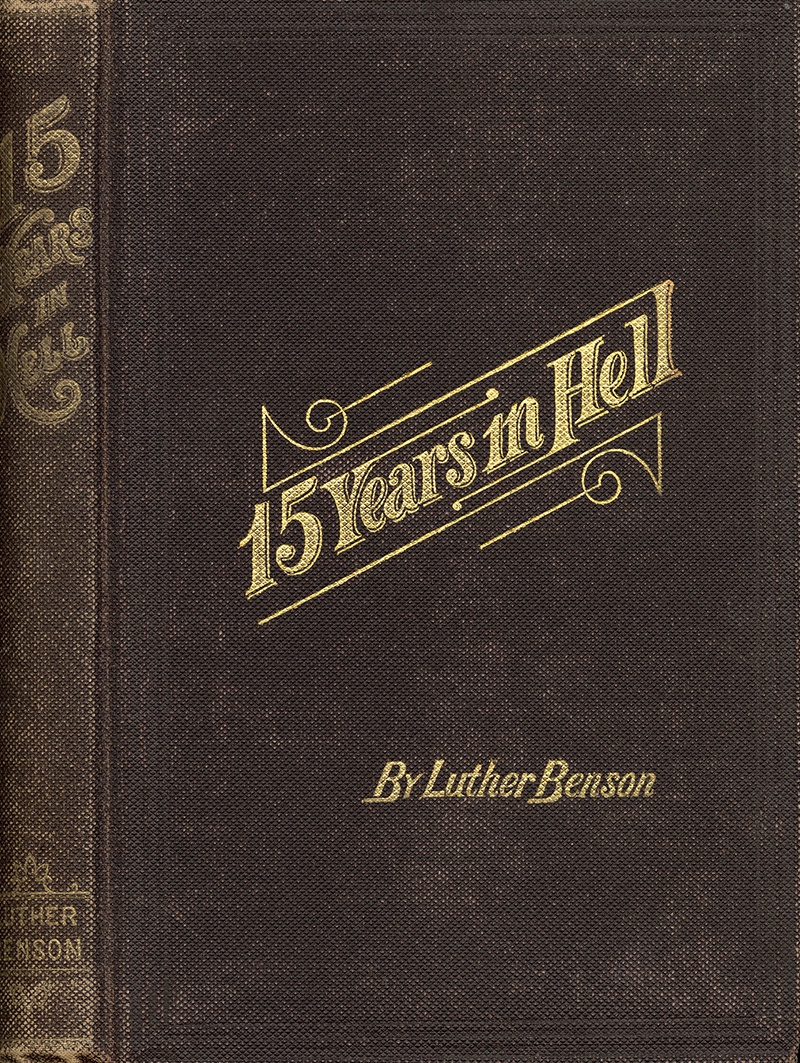

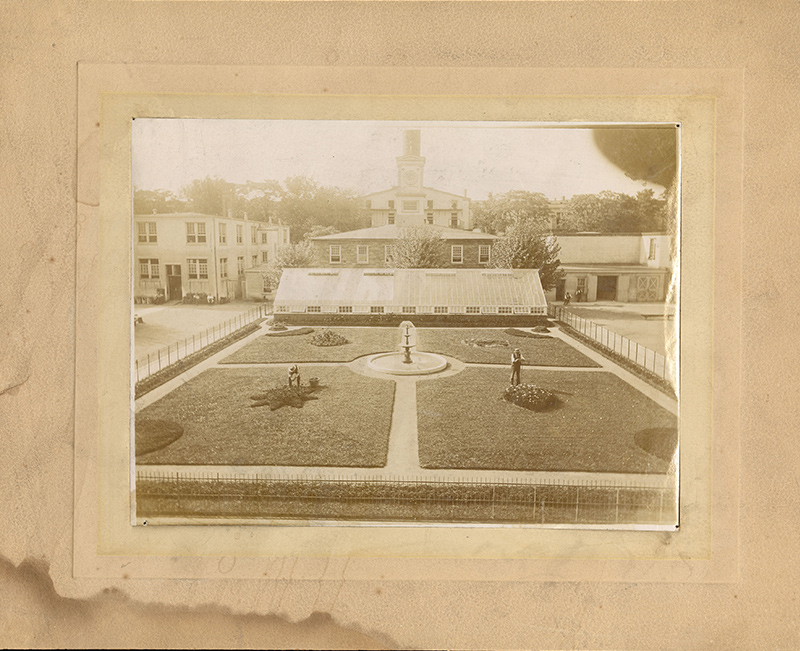

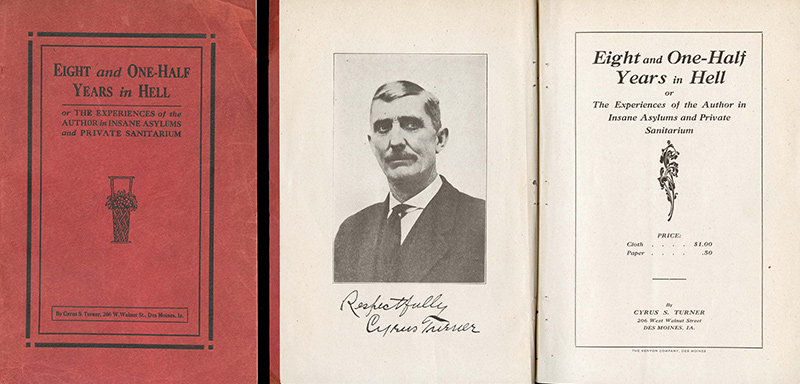

There is more than one side to every story. The annual reports issued by asylums often painted a very respectable picture of patient life, talked of progress, and boasted high cure rates. But the stories in this section present a starkly different experience. These stories, the ones written by the patients, depict the 19th century asylum as a mismanaged, overcrowded, and underfunded place. The treatment offered was misguided if not inhumane. The attendants were untrained and the doctors vindictive, the food inedible and the conditions unspeakable. Many of the narratives here were written to break through the glowing façade presented by the institution and to expose these horrors to the unknowing public, and to a degree they were successful. In a handful of instances, publication led to investigation, and investigation led to reform.