“A place of padlocks and chamber pots”

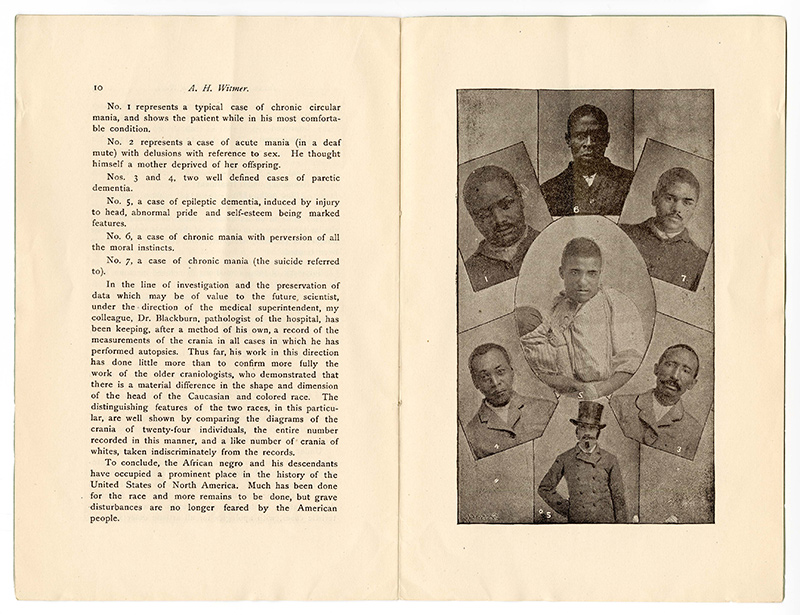

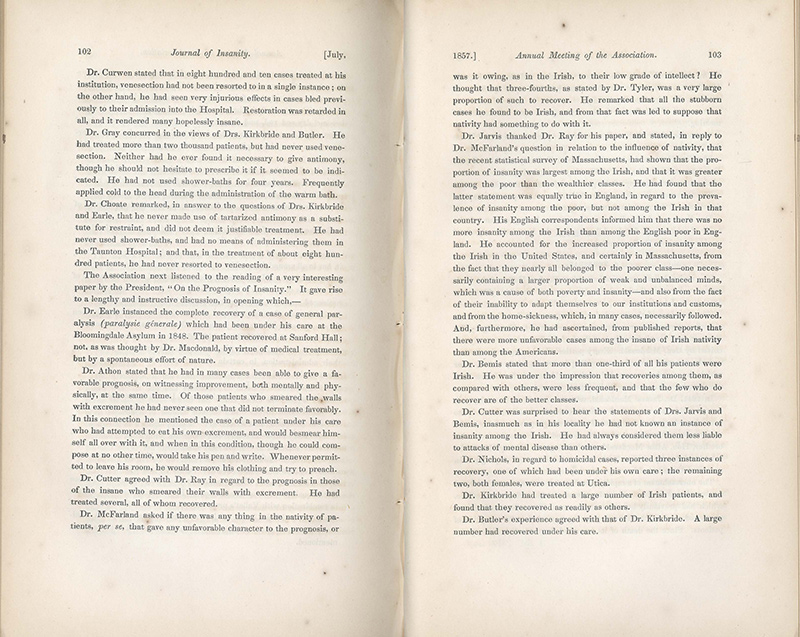

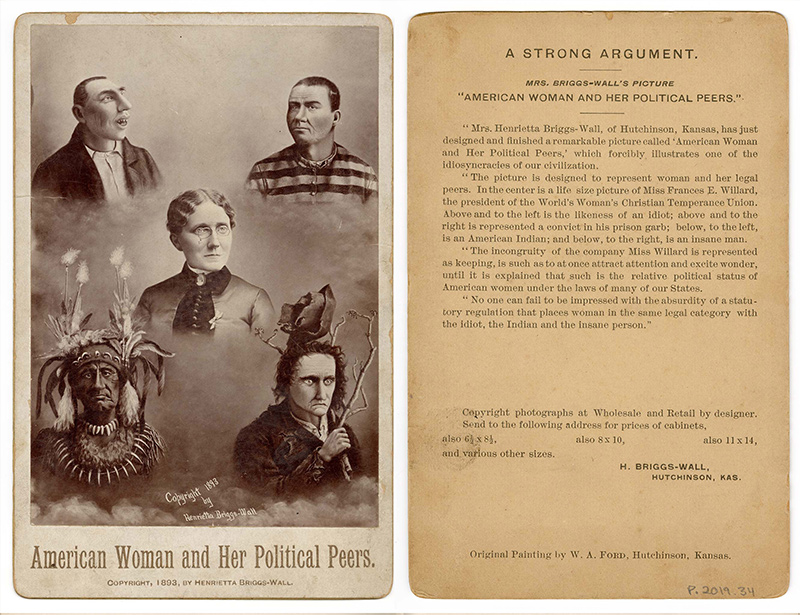

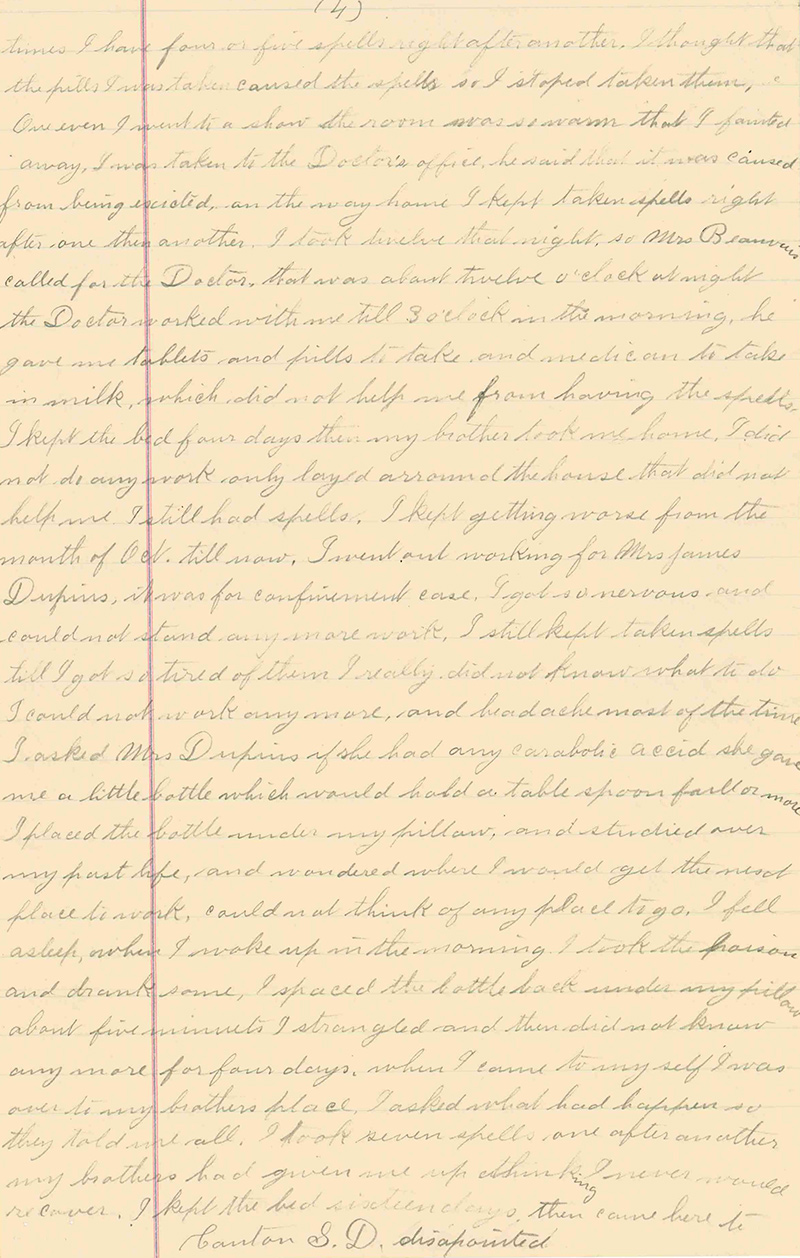

Race, Class, and Mental Health

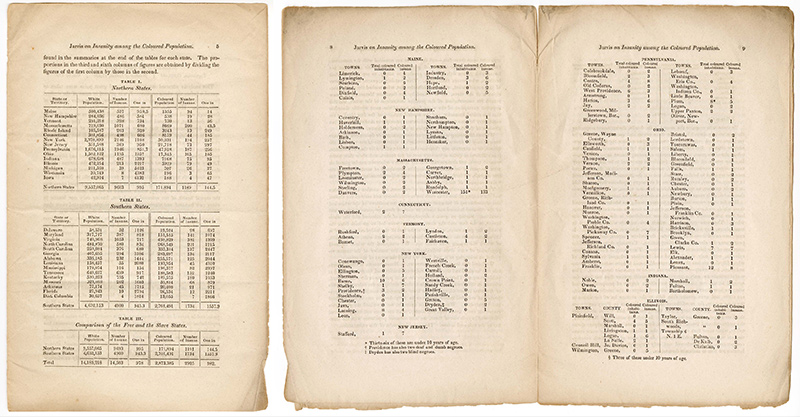

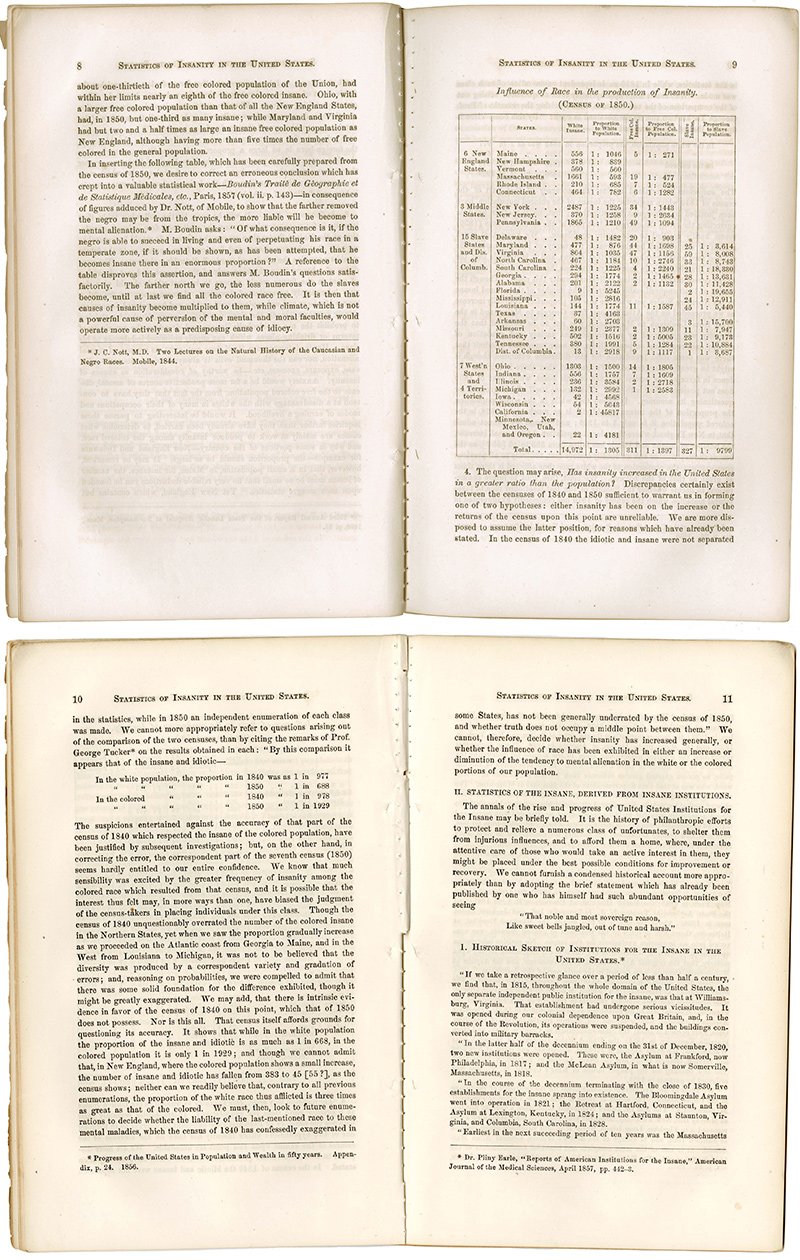

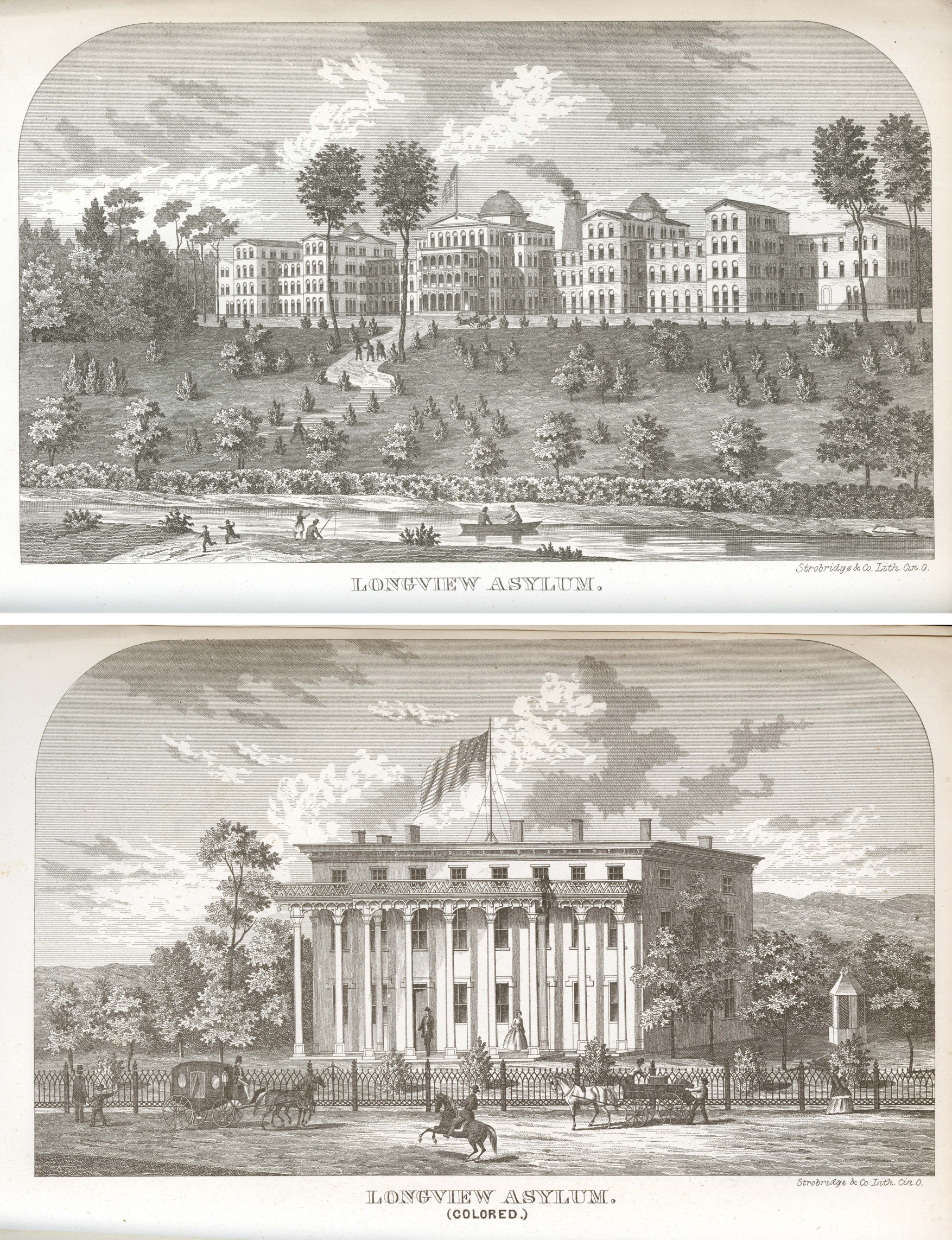

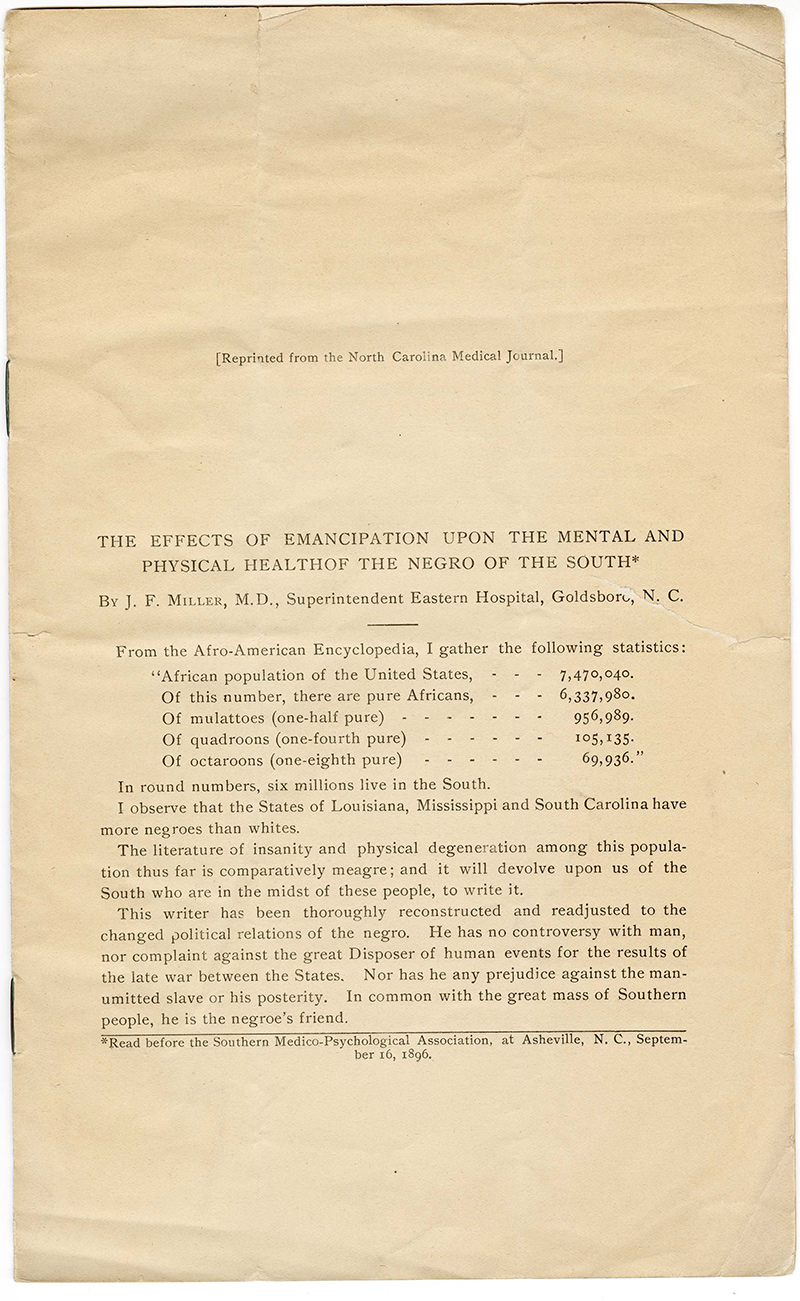

The asylum is a microcosm of the society in which it exists. As such, it is unsurprising that the experiences of Black, indigenous, poor, and immigrant inmates were often considerably more trying than the experiences of their white counterparts in the 19th century asylum. While this exhibition has attempted to centralize the narratives told by asylum inmates, it will necessarily falter when attempting to tell the story of those most marginalized, as their voices were most effectively silenced. Without resources to self-publish, or advocates to aid their release, or even doctors who understood their language, having their voices heard a century and more later requires particularly close and critical listening on our part. We look for their agency in any evidence that remains, and keep in mind that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.