The series of objects in this display tell the multi-dimensional story of Black people’s empowerment through visual symbols. From forced migration aboard overcrowded slave ships to the beautifully ornamented photo album of an illustrious Philadelphia family who charged their daughter to collect the history and musings of their people, this story of resilience is common to all corners of the African Diaspora. We approach this narrative by focusing on images that convey the subversion of racialized power dynamics and those that highlight Black people’s agency. The display culminates in the celebration of a middle-class African American family whose photo album is an invaluable vignette of black self-representation in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Black people continued to “turn the tide” against crude stereotypes about them when they curated themselves in the mediums they chose.

|

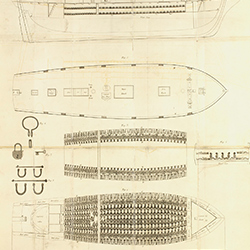

S. Croad and John Hawksworth, “Sketch of the Vigilante” in Case of the Vigilante, a Ship Employed in the Slave-Trade (London, 1823). This powerful and familiar image of a slave ship was published by the Committee of the Religious Society of Friends in London, which was committed to the abolition of slavery in England and Ireland. Notice the very scientific approach with which the ship’s anatomy is dissected and showcased. |

|

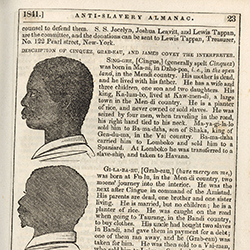

“Amistad Captives,” American Anti-Slavery Almanac, for 1841 (New York, 1840). The two leaders of the Amistad uprising and their interpreter are profiled. Two years after the 1839 uprising, the Supreme Court upheld the ruling of the lower courts, which found that the group had been kidnapped and enslaved illegally. Cinque, Grabeau, and the other Amistad captives were freed. While the ruling did not end U.S. slavery, it re-invigorated the abolitionist movement. The case endures today as a symbol of Black people’s resistance. |

|

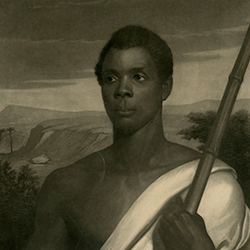

John Sartain, Cinque: The Chief of the Amistad (Philadelphia, 1841).

Mezzotint. Painted by Nathaniel Jocelyn; engraved by J. Sartain. This engraving depicts Joseph Cinque, the leader of the Amistad uprising, standing against a lush African landscape. The toga and walking cane in his hand imbue Cinque and the scene with an air of stateliness and power that was unusual in contemporary depictions of Africans in the U.S. This allusion to a regal and empowered Cinque functions as a reclamation of the African Diaspora’s past and future. |

|

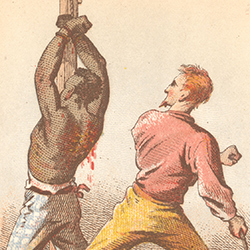

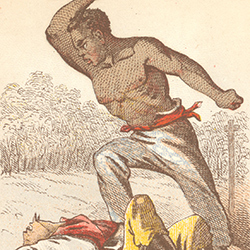

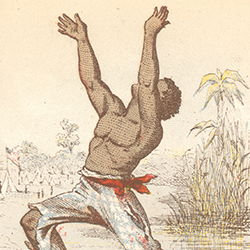

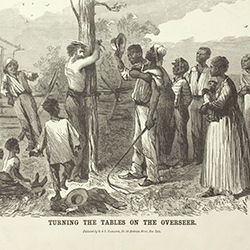

Attributed to James F. Queen after Henry L. Stephens, “Free!,” “Make Way for Liberty!,” “The Lash.,” and “Blow for Blow” from Journey of a Slave from Plantation to the Battlefield (Philadelphia, 1863). Chromolithographic collecting cards. Turning the Tables on the Overseer (New York, 1863). Wood engraving. The depictions in “The Lash,” “Blow for Blow,” and “Make Way for Liberty” chromolithographic collecting cards and the wood engraving, “Turning the Tables on the Overseer” present a stark contrast between the necessary violence perpetrated by the slave and the punitive and arbitrary violence of the white master. |

|

|

Album of Richard DeReef Venning (1865–1922). Stevens-Cogdell/Sanders-Venning

Collection. To see inside the album, click this link. This photo album contains portraits of a prominent Philadelphia family, the Stevens-Cogdell/Sanders-Vennings, and other unidentified people. The family, which descended from Richard Cogdell (1787-1866) and the enslaved Sarah Martha Sanders (1815-1850), was actively involved in political, social, and cultural matters in the Philadelphian Black community. |

|

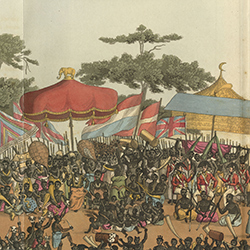

R. Havell & Son after T. Edward Bowditch, “The First Day of the Yam

Custom” from T. Edward Bowdich, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to

Ashantee: with a Statistical Account of that Kingdom, and Geographical

Notices of Other Parts of the Interior of Africa (London: J. Murray,

1819). Reproduction of Hand-colored aquatint. The yam custom, or yam festival, is a five-day harvest ritual celebrated throughout western Africa and other parts of the Diaspora. Each September large festivals are held in Ghana and Nigeria to commemorate the yam harvest and give thanks to the ancestors for their guidance in the difficult cultivation of the yam. In the Haitian Vodou religion, the Manje Yam is a two-day ceremony in which the first yams of the harvest are consecrated and offered to the loa (god). |