|

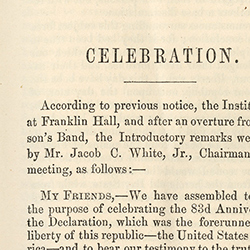

Banneker Institute, The Celebration of the Eighty-Third Anniversary of

the Declaration of American Independence, by the Banneker Institute

(Philadelphia, 1859).

Created by an African American literary society, this pamphlet celebrates the

anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. It states the organization’s

political position on the nation since the establishment of the United States.

|

|

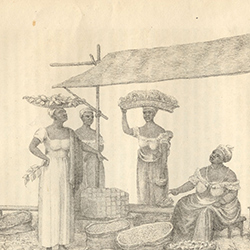

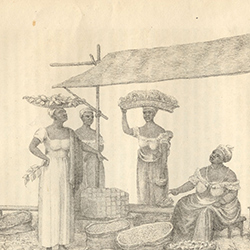

C. Shoosmith, “A Free Negress and Other Market-Women,”

in James Henderson, A History of Brazil: Comprising Its Geography,

Commerce, Colonization, Aboriginal Inhabitants, &c. &c.

(London, 1821). Lithograph.

This image of Black Brazilian market women selling goods shows the importance of

women entrepreneurs in the marketplace. Their presence demonstrated how savvy and

creative Black businesses were in the 19th century.

|

|

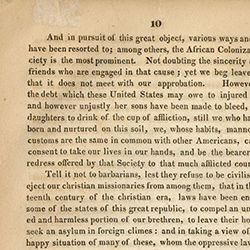

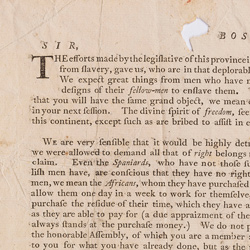

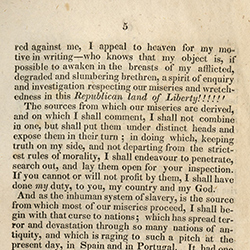

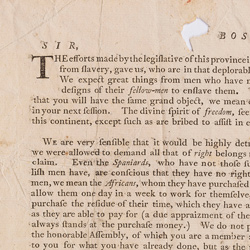

David Walker, Walker’s Appeal, in Four Articles; Together with a

Preamble, to the Colored Citizens of the World, but in Particular, and Very

Expressly, to Those of the United States of America (Boston, 1829).

One of the most feared pamphlets that circulated during the antebellum era, David

Walker’s Appeal told enslaved and free Africans to seek freedom through

self-help and education. Walker was convinced that white Americans would never

elevate the socio-economic status of Black people in America. Thus, he urged

enslaved Africans to take up arms and revolt against their oppressors to attain

liberty.

|

|

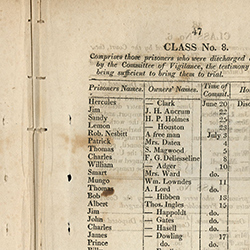

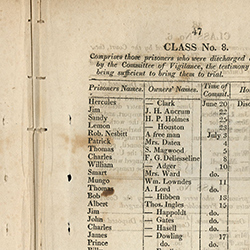

Charleston (S.C.), An Account of the Late Intended Insurrection Among a

Portion of the Blacks of This City (Charleston, 1822). Loan from

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

The monograph printed by A.E. Miller highlights enslaved Africans plotting a revolt

against whites in Charleston, South Carolina. Although many of the insurrections

were stymied by sabotage and gossip, any Black person accused of planning

insurrection was executed for their attempt to be free.

|

|

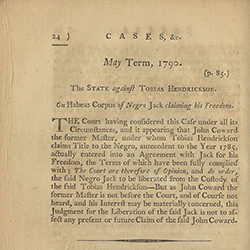

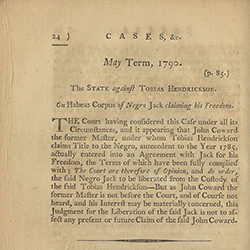

Cases Adjudged in the Supreme Court of New Jersey; Relative to the

Manumission of Negroes and Others Holden in Bondage (Burlington, 1794).

Loan from Historical Society of Pennsylvania

This monograph highlights New Jersey Supreme Court cases involving the manumissions

of Black people. In the case of an enslaved African named Jack, New Jersey Supreme

Court granted him freedom based on the agreement made between him and his former

slaveholder.

|

|

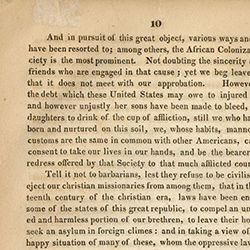

American Society of Free Persons of Colour, Constitution of the American

Society of Free Persons of Colour (Philadelphia, 1831).

Colored Conventions proliferated during the 1830s and 1840s. They espoused political

theories of racial unity and consciousness in Black America. Most conventions

emphasized how Black people should pursue true freedom and liberty in America by

various means.

|

|

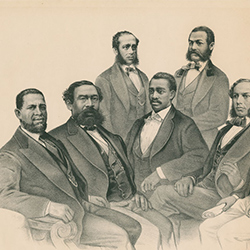

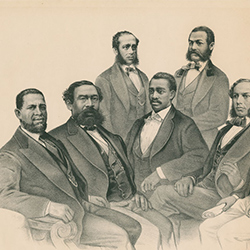

Currier & Ives, The First Colored Senator and Representatives

(New York, 1872). Lithograph.

These seven individuals embodied Black politics during the Reconstruction Era. While

serving in their respective positions, these politicians advocated for public school

education, universal suffrage, war amnesty, funding national infrastructure, labor

rights, and civil rights.

|

|

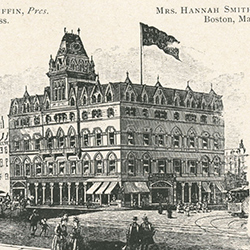

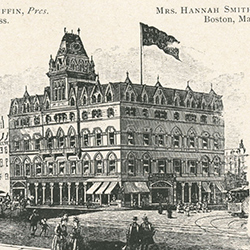

National Association of Colored Women (U.S.), Historical Records of

Conventions of 1895-96 of the Colored Women of America. (United States,

1902).

Black women were heavily involved in shaping politics through their labor in the 19th

century. Although they were often excluded from male-dominated colored conventions,

they still found ways to impact the socio-political lives of African Americans.

|

|

M. & N. Hanhart after F.E. Forbes, “Gezo, King of Dahomey” in Frederick

E. Forbes, Dahomey and the Dahomans: Being the Journey of Two Missions to

the King of Dahomey, and His Residence at the Capital, in the Years 1849 and

1850 (London, 1851), vol. 1.

King Gezo of Dahomey (present-day Benin) is depicted here as regal and commanding. He

was wealthy and powerful but made his riches selling other Dahomeans to European

slavers. His presence complicates the role of African elites in the trans-Atlantic

slave trade amidst a robust abolitionist movement.

|

|

|

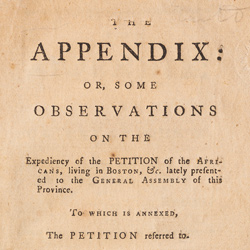

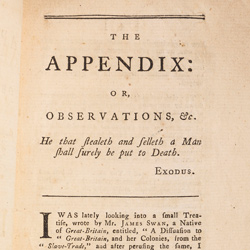

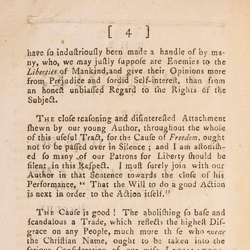

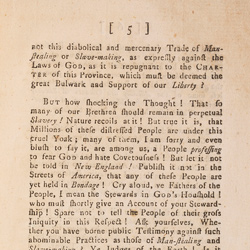

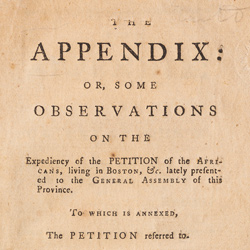

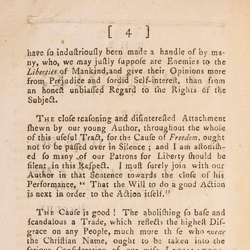

Lover of Constitutional Liberty, The Appendix: or, Some Observations on

the Expediency of the Petition of the Africans, Living in Boston, &c.

Lately Presented to the General Assembly of This Province (Boston,

1773).

In this petition to the Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson and the Province’s

House of Representatives, enslaved Blacks living in Boston requested to be freed

from slavery.

|

|

|

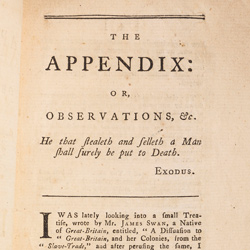

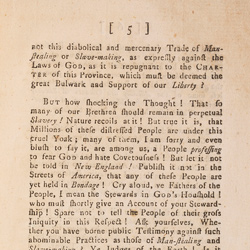

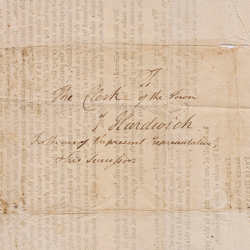

Boston, April 20th, 1773 (Boston, 1773).

This petition was written by four Africans to the General Assembly of Boston and

advocates for slavery to be ended in Massachusetts.

|