|

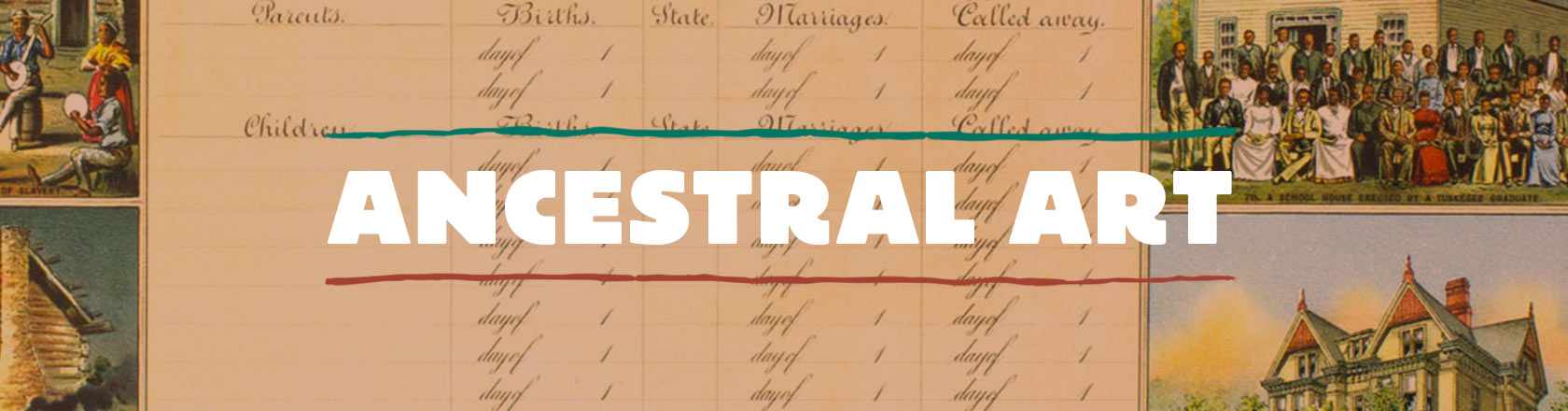

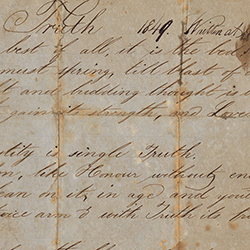

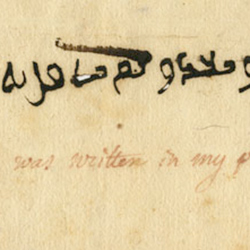

Arabic Fragment, a West African Gris-Gris, 1773.

A gris-gris or wanga is a traditional West African talisman

consisting of transcribed prayers, roots, herbs, and other objects used to ward off

evil. An enslaved Islamic priest wrote this snippet of Arabic calligraphy. It was

written in Leyogan in colonial Saint-Domingue (now Ayiti/Haiti). Translation:

“In the name of God, Most Gracious, Most Merciful Say: He is Allah, the

One and Only! Allah, the Eternal, Absolute; He begetteth not nor is He begotten.

And there is none like unto Him.”

|

|

|

“Desalines” from Código Formado por los Negros

de la Isla de Santo Domingo de la Parte Francesa, Hoi Estado de Hayti

(Cádiz, 1810). Engraving.

“Incendie du Cap. Révolte Général des

Neègres. Massacre des Blanca” from Saint-Domingue, ou

Histoire de Ses Révolutions (Paris, 1815). Hand-colored

engraving.

After a decade of revolt, former Saint-Domingue slaves faced down Napoleon

Bonaparte’s army, which wanted to re-enslave them. Arriving at

Cap-Français in 1802, Bonaparte’s brother-in-law Charles Leclerc,

ordered General Henri Christophe to surrender; he refused, and revolutionaries

burned the city. Two years later, Haiti was an independent nation, the first Black

state established by former slaves, and popularly known as the “horrors of San

Domingo” due to claims of wanton violence against whites by Haitians.

Haiti’s presence angered Euro-American powers and they ostracized the nation

and threatened its sovereignty.

|

|

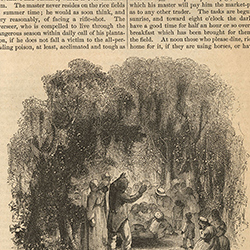

“A Negro Funeral,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine

(New York, 1859). Wood engraving.

Across the African Diaspora, the honoring of the ancestors is important. Encapsulated

by the Ghanaian Akan adinkra nwame nwu na mawu (“God cannot die, so I cannot die”),

the belief was an especially cherished one. During slavery, Black funerals were held

in secrecy, leading to lurid depictions by outsiders unversed in the joy of carrying

an elder into the realm of the ancestors. Funeral rites serve to connect the

recently-deceased and the community with the traditions that they maintained and

would pass down for generations.

|

|

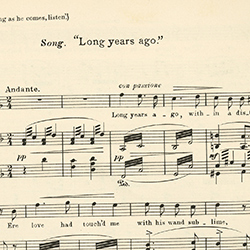

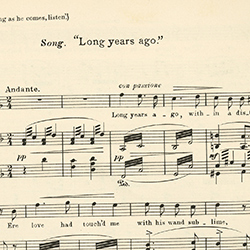

Paul Laurence Dunbar and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Dream Lovers: An

Operatic Romance (London, 1898).

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was not only a composer and musician but also a civil rights

activist. When he learned that Paul Laurence Dunbar, America’s most celebrated

“Negro” poet, was in London, Coleridge-Taylor sought him out and asked to set

Dunbar’s poems to music. They created “African Romances” in 1897 and in 1898 Dunbar

penned the lyrics to Coleridge-Taylor’s music and produced “Dream Lovers” in 1898.

It premiered in a recital hall in Croydon, England.

|

|

Photo Illustrators, Young African American Woman (Philadelphia,

1930). Gelatin silver. Gift of Joseph Kelly.

The identity of the “young African American woman” in the photograph and its former

owner are unknown. The deep creases and chipping may be indicative of being folded

and carried around by someone who valued something as special and expensive as a

photograph. The young woman looks at us through the creases, from the past to the

future; she hoped would remember her image.

|

|

Watercolor by Mary Ann Elizabeth Codgell, ca [1849?].

Stevens-Cogdell/Sanders-Venning Collection.

|

|

Poem by Cordelia Sanders, ca. [1849?]. Stevens-Cogdell/Sanders-Venning

Collection.

|

|

Sarah Mapps Douglass, Honeysuckle, ca. 1845. Watercolor.

This image, created by Sarah Mapps Douglass, depicts a stem of a honeysuckle.

Douglass was an elite African American Quaker in Philadelphia who was known for

being an educator and community activist.

|

|

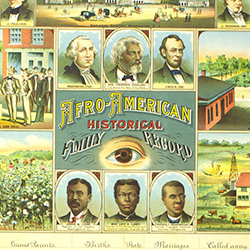

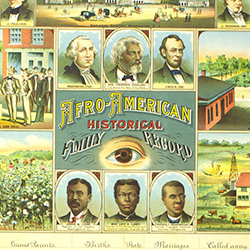

Afro-American Historical Family Record (Augusta, Ga., 1899).

Chromolithograph.

In the wake of Emancipation, the maintenance of family records can be seen as a

legitimization of the Black family and their progress from enslavement. This dream

of a better family life can be seen in the contrast of conditions under slavery with

an idealized liberated future that can lead to becoming someone worthy of being

depicted in portraiture. It is citizenship idealized.

|

|

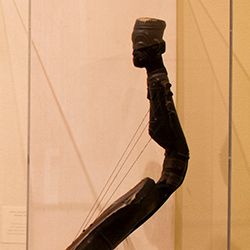

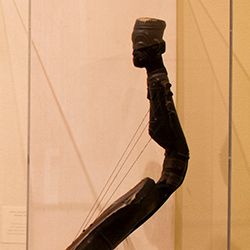

Mangbetu Harp (Democratic Republic of the Congo), ca. 1910. Loan from Dr.

Deirdre Cooper-Owens.

The harp’s neck is surmounted by a woman’s head with a traditional Mangbetu coiffure.

The coiled copper wire found on the neck of the harp represents the geometric body

painting that often adorned Mangbetu women.

|